Chapter 5

Crash

Course

“I simply

can’t believe it,” I said to Wilbur, more loudly than necessary. I had said the

same thing, more or less, several times during our walk back from the

restaurant to Ernest’s, and several times more in the hour or two since, but I

still could not get over it. “It’s absurd,” I said, re-seating myself in one of

Ernest’s sofas.

“Why?” he

replied calmly.

Having just

discovered an identical toilet to Wilbur’s, I ensured another visit by

refilling a glass of very fine port. “Well, for a start, it took centuries just

to get a five-day working week. Are you telling me you’ve had a five-fold

reduction in just forty years?”

“Yes. It

was easy to arrange once the economic engine had an off-switch installed.”

This was

too cryptic for me, but he must have realised. He took a long sip of his port,

declined my offer to top him up with a polite shake of his head, and continued.

“Technological

advance has always reduced the need to work, but the five-day working week nevertheless

persisted long beyond any real need for it mostly because of antiquated

economic rules that constantly demanded ever more work, ever more jobs, ever

more consumption—in other words, economic growth. And this was despite much work

being not simply unnecessary but often counter-productive, or worse. It’s been

estimated that forty percent of all work in the early part of the twenty-first

century was devoted to cleaning up the unwanted side effects of the rest. There

was another estimate, by Fuller, nearly a century ago—you yourself drew my

attention to it…”

I was ready

to deny that, but stopped when I realised I had

read Buckminster Fuller, in my teens. I even had a vague memory of what Wilbur

then cited: “He claimed only thirty percent of all work was really needed—that

was the proportion devoted to genuinely productive work. The rest either made

no real wealth or was even destructive. Arms manufacturing, insurance

under-writing, banking.”

“Banking!”

I erupted, only to be diverted by a sudden concern that my next words might be

‘Polly want a cracker’. My concern proved groundless: “How could anyone regard

banking as destructive?”

“Perhaps

ask someone who had their mortgage foreclosed. But even if not considered destructive,

banking was certainly unnecessary. All that energy and time, all those

resources, wasted on meaningless numbers in constant flux. No wealth created,

not even distributed. No wonder it was one of the first jobs done away with.”

“What are

you talking about? Done away with!”

“Just that.

Banking no longer exists. You said you’re a banker, but that would make you

unique, in this country at least. Unless the handful of people now involved in

financial account-keeping proved willing to adopt that antiquated term for

their work. I doubt it. It’s rarely used these days except as a term of

derision.”

I was

flabbergasted. Speechless. I had already been told that I did not exist in this

world, this alleged future—not as Steven Stone. Now I’d been told my job did

not exist either—my career!

This simply

would not do. I had to exist. As myself. And with my career intact. Wilbur was

trying to confuse me—that was it. Well, it wouldn’t work. I silently resolved:

I would find the flaw in his logic, the weakness of his arguments and claims. I

would listen and learn, so I could disprove

what he was saying. No system, however futuristic, could eradicate banking. Or

me for that matter. I would survive. I was determined.

I was also

powered by port.

“All

right,” I said, expecting Wilbur to trip over his tongue with the slightest

prompting. “For the sake of argument, let’s assume banking doesn’t exist, nor

any other of the allegedly useless work. I still don’t see how that leaves a

seven-hour week.”

“Well, if

only thirty percent of work that occupies a population for five days a week is

truly useful, and if that’s all that’s actually performed, then sharing it

would require only about a one-and-a-half-day working week. Right? But of

course that’s ignoring unemployment rates, and so-called ‘hidden unemployment’,

as well as many technological improvements made since a five-day week was

extant. What was needed—and eventually done—was not just to abandon all

unproductive work, but to automate as much as was desired of everything that

remained, and share the rest. Of course, it was necessary also to learn to

build to last instead of to obsolesce—to minimise or avoid pollution,

resource-hungry processes, non-renewable energy use—to produce and consume more

responsibly and efficiently.”

“Is that

all?” I grated, sarcastic and unconvinced. “That was enough to leave you a

one-day working week?”

“Not

straight away. But it fed on itself: with less work, less resources were needed,

and less pollution and other damage was caused. Less led to even less. Indeed,

a substantial group of people think a one-day working week is too much, that it

should be at least halved. Personally I think they tend not to appreciate just

how much work that really needed doing, but couldn’t make anyone a monetary

profit, simply wasn’t done under capitalism. By the time it was superseded, the

world was in a pretty fragile mess. If it hadn’t been, a half-day working week

might now be possible.”

He’d

mentioned some of this earlier (along with the obvious-in-hindsight explanation

of the meaning of ‘needays’—days needing

to be worked), but still it did not persuade me. “It’s not possible,” I said

with certainty, before downing a sizeable fraction of my glass.

“Of course

it’s possible. It’s been made

possible. It’s all around you.”

“It’s a

figment of my imagination.”

“It’s a creation of many people’s imaginations.

And a choice made by society from a

wide range of possibilities. The rules, the way it’s organised, they simply

work better, are better designed, than the ones used in previous centuries.”

“But do

they come with a free set of steak knives?!” I blurted, the port starting to go

to my head. I had to be dreaming, I

was sure of it now. As dreams went, this one had never seemed exactly normal,

but it was starting to wander off into realms too absurd to be mistaken as

real. “I still can’t believe it. What you’ve said might explain why less work

is possible, theoretically, but it

can’t be reconciled with the need for economic growth. Any economy trying what

you claim has been done would have found itself in a massive depression.”

“It would

have, if that was all it did. But for an economy, like an individual,

depression is a state of mind. Growth is not

essential. For a capitalist system, with capitalism’s rules, it is—growth is the only way to avoid

collapse—but other rules and arrangements can be adopted which make growth

unnecessary. Which is what was done. Necessarily. And just in time. There’d

been so much growth that to have had much more would have been suicidal.”

“I don’t— I

can’t…,” I stopped faltering long enough to realise I had no retort other than

to repeat myself. “But growth is

essential. It’s the only way to bake a bigger economic cake, so everyone can

have more to eat for the same share.”

Wilbur

smiled disarmingly. “It was certainly promoted that way. A cure-all. A single

easily digestible measure of national success in a complex hard-to-fathom

world. But a bigger cake need not be sliced up the same way—too often, a few

got bigger slices of a bigger cake, while most others got the same or less. Nor

need a bigger cake taste as good nor provide as much nutrition, especially when

some slices are toxic. In any case, you can’t always grow. Firstly, you need ideas—even ill-conceived ideas—of how to grow, how to make a profit. But

since a perpetually sufficient quantity of ideas can never be guaranteed,

growth had to sometimes turn to

shrinkage, and the economic cake had to periodically curdle. Recessions and depressions

were inevitable.”

“Maybe

growth could not spring eternal,” I interjected, “but not simply because of a

lack of ideas.” Vague memories of economics lectures at Uni sprang to mind.

“The business cycle is affected by a huge range of factors.”

“True, but

ultimately they can be traced to a single one: profit. Once the whole idea of

financial profit was thrown out, things settled down straightaway.”

“What do

you mean ‘thrown out’? Are you telling me you have a system that doesn’t allow

profit? That’s ridiculous. It was the absence of the incentive of profit that

prompted communism’s collapse.”

“Actually,

the inefficiencies of central planning had more to do with it. In any case, there

are incentives other than profit. Better ones. More effective ones. The urge to

avoid boredom. To feel useful and valued—or, if you prefer, to satisfy and

please others. The thrill of achievement. Self-development. Even the hope for

immortality through exceptionality.”

“People are

satisfied by that?!”

“Perhaps

not by that alone, but the abandonment of profit has had many benefits: one-day

working weeks, no more business cycles—”

“And what costs?” I interjected before he could

swamp me with claims. I was ready to start a list of my own, beginning with

inadequate or no investment, but he replied too quickly.

“None that

weren’t anticipated and avoided by appropriate counter-measures. Profit was

always very counter-productive. As well as utterly taken for granted. You win

some, you lose some: a truism hiding the obvious, that any profit must have a

counterbalancing loss. Which means that even if everyone competes with maximum efficiency, there will still be losers—and

no surety for winners of not joining them. Poor people, poor nations, always.”

“Marx said

as much ages ago,” I exclaimed angrily. “Didn’t he? But you said profit is the

ultimate factor behind business cycles. Why? You haven’t explained that at

all.”

“Sorry, I

digressed. It can be explained very simply. If prices include profits, not all

goods produced can be afforded. And if an economy can’t afford its own prices,

then sooner or later it has to falter.”

I was

expecting more—much more—but he remained silent. Had he finished his

explanation? “That’s Say’s Law isn’t it?” I said, losing patience. “No, wait—that’s

the opposite of Say’s Law. It claimed there was always enough money to afford everything produced. Although Keynes

disproved that a century ago.”

“Indeed, but

Keynes did not demonstrate how fundamentally

wrong Say’s Law is. Let me show you.” Wilbur found a pen and paper and began to

sketch something resembling the standard textbook depiction of the economic

flow.

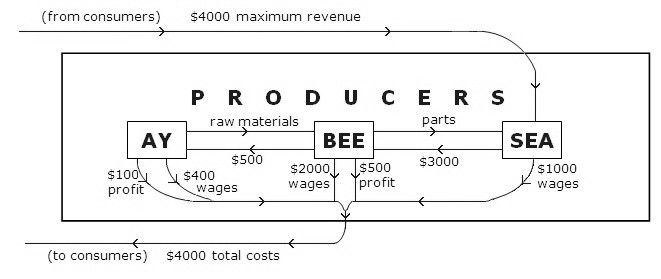

“Think of a simple economy with just three producers – or three groups of producers, each at different stages of production. One company or group of companies, Ay, digs up raw materials and sells them to another, Bee, which fashions parts from them which they sell to a manufacturer, Sea, which turns them into completed retail products. The money paid by Sea to Bee covers Bee’s wages and profits, and Bee’s payments to Ay covers Ay’s wages and profits. Add all that up, as well as Sea’s wage costs, and you get the total cost of the retail goods. But if the goods’ prices exceed their costs – that is, if their prices include a profit – then they can’t be afforded. The money paid to people during the construction of the goods is only enough to cover their costs, and even then only if Ay and Bee spend all their profits on Sea’s products. If Ay or Bee retain profits, Sea loses by the same amount.”

“I don’t follow,” I reluctantly conceded.

“All right. Let’s give it some numbers. Bee pays Ay $500 to cover its profit of $100 and its wages of $400. Sea pays Bee $3000 to cover its $500 payment to Ay, its wages of $2000 and its profit of $500. And Sea has its own wage bill of $1000. Add it up – a total of $3400 has been paid in wages for all three companies, and $600 has been made as profit by Ay and Bee. So there can only be $4000 available to spend on Sea’s products. Which, of course, matches Sea’s costs, but not its profit-inclusive prices. However, if Ay and Bee keep their profits, then there’s only $3400 in wages to cover Sea’s $4000 in costs – it loses by the same amount that Ay and Bee profit. If Sea is a group of producers, some of them might profit, but the total for all of them will be a loss equal to the profits of Ay and Bee. All in all, profits balance losses, and the economy can at best afford its costs but not its prices – not as long as they include profits. But if the economy can’t afford its own prices, then sooner or later it has to falter – businesses will go bankrupt and the economy will go into recession.”

“There must be some mistake,” I said. I’d followed his words precisely this time, and found no fault, but there had to be one. In just a few minutes – this dream was turning into a macroeconomics lecture – he’d explained something fundamental, yet which somehow had never been mentioned in all the years I studied economics at school and university.

“I assure you there is no mistake. Not all profits can be afforded. The issue was raised over two centuries ago, though it received almost no attention after the Great Depression until earlier this century. But since then, it’s been verified time and again. Not all can win at competition.”

“But some goods must sell for a profit.”

“Certainly, some do, but others don’t. There’s a mixture of profits and losses, the total balancing to zero. But for those who lose, and any employees they might shed, there is less to spend, so they retard growth, which encourages recession. Capitalism thus has instability in-built, a proneness to fall over sooner or later. A direct and unavoidable consequence of its inclusion of profit in prices.”

“Wait a minute.” To my surprise, I felt angry. But not so much I couldn’t think clearly. “What about credit? People could borrow money to afford profit margins.”

“That’s exactly what they did. And I suppose you could say it worked – sort of – but only temporarily. It was really just a delaying tactic. Initially, credit allowed more profits to be afforded, but eventually it exacerbated the likelihood of loss, because the lenders themselves were trying to profit. The only way for sufficient numbers of businesses and lenders to keep profiting was for debt to increase continuously and at an escalating rate: new debt had to be issued to cover the profit gained by earlier loans and their repayment, then the same and more again in the next round, over and over. But injecting credit into economies more quickly than debt repayments siphoned it back out not only reinforced the real problem, it also could not be sustained. For years at a time, the attempts did manage to ensure plenty of profits, but only by putting off the day of ultimate reckoning via a precarious and ever-mounting stack of cards prone to eventual collapse when one decent economic sneeze caused the lenders themselves to lose – as inevitably happened. Then loss could no longer be delayed, with the result that economies sank into recession or depression.”

Perhaps I wasn’t thinking so clearly. The credit squeeze that ushered in the Global Financial Crisis came suddenly to mind. But I wasn’t ready to give up. “What about government spending? Can’t that afford everything?”

“How? Governments always afforded things by borrowing money themselves, which, as I just explained, doesn’t work. Or they tried taxation, which doesn’t increase the funds available for purchase – it just redistributes the existing pool of money.”

I was momentarily quiet, stymied by his words – and ill at ease because of their use of past tense – but grappling for a response. Hoping for inspiration, I drained the rest of my port. An idea immediately arrived, convincing me in a moment. “I know! There’s always extra money from exports.”

“Hardly always. Certainly not if more is spent importing than is gained by exporting. But even if there’s a net gain from exports, it just passes the problem to another country. Imports and exports only redistribute money between nations, they don’t increase the net amount available to all.”

Again, I struggled to find a retort, and when at last it presented itself, I was again sure it was the right one. “Growth!” I blurted out, smiling widely. “Of course, that’s why it’s necessary. Economic growth provides the money to afford everything.”

“No it does not. Economic growth simply means more money is being spent. It may come from increased profits, credit, export income, and/or government spending – but none of these on their own or in combination can afford every profit, so neither can growth. The problem stems not from how much is spent, but how it is spent. At best, growth can only provide short-term success for some, without actually addressing the fundamental problem. As I said, not everyone can win a competition. Some win, others lose. And the over-riding consequence of that fact is that a profit-based system is inherently unstable.”

I was still not convinced. I stared at his diagram, repeatedly adding up the figures without ever getting different results, and desperately trying to figure a way out. My mind started to broil. If this was all a dream, how could I have become aware of what Wilbur had just told me? We had a sceptical economics tutor one year at Uni – had he mentioned it? It certainly wouldn’t have been part of the curriculum. Or had I perhaps somehow recognised it myself but not consciously? Was this dream – this ridiculous complicated dream – the only way it could be brought to my proper attention? Why after so many years? Surely my subconscious had not been brewing over it all this time? Surely it had not taken this long to figure it out?

“By the time this was widely accepted,” continued Wilbur, “capitalism had become an arbitrary choice, but its use, habitual. So it hung on, persisting against its own failure.”

“What option was there?” I responded hotly. I felt obliged to defend what I knew. “Socialism had failed. There was only capitalism.” I surprised myself at my use of the past tense, but was distracted by inner doubts as well as caught up in the discussion.

“Let me put it this way,” said Wilbur. “If I only know how to make two types of cake, I might suggest the chocolate cake, not the orange cake, is the most effective way of keeping hunger at bay – but only if I close my options now. Otherwise, one day I might learn to bake, say, a poppy seed cake.” He did his best to stifle a yawn, but it was obvious nonetheless. “It’s getting late,” he said, glancing at a watch.

Another surprise. I glanced outside to verify it was still twilight, then at the kitchen clock. “You’re joking. It’s barely six thirty. Don’t tell me everyone goes to bed at dusk in this so-called future.”

“No, they don’t. However, for the most part, I do.”

“You some sort of anti-vampire?”

“Right. Need a blood donation?” He smiled in a way which, for some reason I could not fathom, gave me a sense of discomfort. “My sleeping habits are unusual, I admit, but we all have our idiosyncrasies.” He drained his glass. “I have to return home, Ernest.”

“Steven!” I said between gritted teeth.

“Sorry,” he said as he began to stand. “You should try and get some sleep yourself.”

“I’m already asleep, remember?”

He gave me a considered look, but did not respond for some time. “If you need anything, my number is on your babel.”

“No, wait, please stay.” I did not want to be left alone. “Just a few more minutes. I’m not sleepy at all.” Even if I had been, I would have resisted falling asleep within this dream. I certainly didn’t like the idea that I was supposed to have already slept a day away.

“Probably from having woken so late,” said Wilbur. “But I really must get home.”

“What about transferring my needay? You said in the restaurant you’d show me how.”

“Right,” said Wilbur, blinking rapidly. “I did. Well, fortunately, it won’t take long.” He paused in thought momentarily. “We’ll use your computer, I think – a bit easier than a babel.”

I followed him into the study. I hadn’t realised a computer was there when I’d been in the room earlier. Its screen was as thin as soft cardboard, and despite its flatness about as flexible; its top edge was adhered (I’m not sure how) to the edge of one of the shelves above the desk, the rest hung below without any visible connection to anything else. What material it was made of I could not guess. There was no box with actual hardware as far as I could tell (I later spent some time looking for it without luck, so I had to assume it was either wirelessly networked from a different room or somehow contained within the display screen). When Wilbur turned it on by tapping the screen with a finger, there was no loading phase – the desktop was instantly available. There was also no mouse – Wilbur tapped one of the desktop icons, and almost immediately an Internet site appeared (the browser looked different but I still recognised it as the same freeware I used at home).

The Internet page announced itself as the official city of Chord site, and included a roster of all work scheduled to be performed by the city’s entire workforce. I don’t mean the city council either. I mean every person who lived within the city’s borders. Wilbur made a quick flurry of finger taps and slides, interspersed twice with text he typed using a very thin keyboard on the desk, with no apparent physical connection to the screen. In no time, Wilbur found my name – or rather that of Ernest. Listed with it was his work schedule for the year. I was stunned, yet again. It was surprising enough to see only seven hours of work listed for each week, but I found it even harder to accept that there would be four different locations and types of work to perform over the same year. Every three months, the job changed to something totally different. According to what was displayed, Ernest had already spent time that year delivering groceries, and assembling children’s toys, and was scheduled for cleaning in the year’s final quarter.

“Ernest must be a very poor historian to be doing work like this,” I said. “What was his award really for? Most outstanding research error?”

“You are— he is well respected in the field.”

“Then why does he spend so much time in menial jobs? For that matter, how does he earn enough from them to live this comfortably?” I swept my arm to indicate the house.

“To answer that properly would take too long. Some other time perhaps. Suffice it to say that you, like everyone else, are rewarded suitably for the labour you perform. But more fundamentally, a standard of living similar to this is your birth right. Now, please observe as I transfer your needay.”

There was little to observe: a few finger movements selected the date in question – which I was a little surprised to find was almost two weeks earlier than the day I fell asleep – and a ‘transfer’ option, at which point Wilbur typed Alice’s full name in the resultant dialogue box. The computer responded with the name (and address) of the closest match in its records, and asked that it be verified as correct, which Wilbur did.

“That’s it?!” I said.

“That’s it,” replied Wilbur, okaying the screen. “Though Alice will need to verify it at some stage.”

“But where’s the security? There’s no logon code, no personal ID number, nothing.”

“You are identified by the computer, nevertheless.”

“O? It knows what I look like?”

“Yes,” said Wilbur, deadpan. “Though a hair cut can sometimes fool it.”

I gave him what I hoped was a suitably withering gaze.

He stifled another yawn. “Like your babel, input from this computer address identifies you to the network as Ernest—”

“Steven.”

“Whoever. The point is, like most, you’ve elected not to use the logon option.”

“But then someone else could use this computer, and transfer my work to them.”

“Yeeesss,” said Wilbur, “but it would be picked up the next time you turned up for work.”

“What if it was done just before I went on a long vacation?”

Wilbur stared at me with a blank expression. “Why won’t you let me sleep? What possible benefit would what you suggest have for the person supposedly doing it?”

“My wage, of course!”

“Your…?”

“Isn’t it obvious?”

Wilbur sighed, then spoke so slowly I expected him to start swinging a chain watch in front of my eyes: “Your income would be the same, whether you worked or not.”

I loudly snorted a sceptical chortle. “A guaranteed income?” I scorned, smiling in disbelief.

He looked me in the eyes, blinking widely. Slowly, almost melodramatically, he raised a hand and repeatedly tapped his index finger on a spot midway between his eyes. “More or less,” he said. His eyebrows furrowed briefly, as if remembering something, then he suddenly moved his fingertip to tap the end of his nose.

I stared at him, incredulous.