In the name of the Profit, the Job, and the Holy Growth

Worshipping false gods comes with many a high price.

A growing economy, by definition, spends more money over time. If it spends less, even the tiniest percentage less for just six months, it falls into recession – reason enough to try to grow relentlessly, perpetually, to require ever more activity, ever more building, extracting, transporting, generating, producing. A pity it’s impossible: if we keep increasing our extraction of the top ten minerals, for example, by the modest three percent growth rate economies usually aspire to as a bare minimum, then in a thousand years we’d need to be digging up an amount weighing more than the entire earth.[1] Talk about digging your own grave.

A pity too that growth concerns only quantity not quality: perhaps forty percent of all money spent cleans up the mess made by the rest.[2] Bad enough in the short-term, but potentially disastrous in the long run. For example, various corporations keep pumping out greenhouse gases as they amass profits and help sustain growth. They are exonerated by widespread and dominant faith that ‘the market knows best’, that some of the profits gained will fund investment to eventually discover new ways to operate without the alleged ecological costs (such as by developing renewable alternatives). Some governments might try to hasten market progress by imposing carbon taxes and emission trading schemes which increase costs and add layers of complexity but do not directly change the methods in use nor the message: keep operating in ways seen as dangerous until you can eventually afford to figure out how to operate safely.[3] Keep doing things wrong until you can afford to do them right. Profit and growth first, all else second. If the same approach was taken towards thieves, they’d be allowed to keep stealing until they could afford to go straight.

Even putting aside the damaging and unsustainable nature of growth, it seems ironic that market economies invariably function in ways that work against growth. Market competition compels businesses to try to maximise profits, achieving this most easily by wage cost reductions, either via automation, increased productivity, or out-sourcing to cheaper labour in other nations. But as a result, jobs are lost, leaving consumers with less money to spend, and hence, businesses with fewer potential buyers of their goods.[4] Because this works against both profit-maximisation and growth, replacement jobs must somehow be created – perpetually.

As well as businesses and workers, banks and other financial institutions have a vested interest in the creation of jobs and maintenance of growth: for loans to producers to be repaid, they must finance enterprises that eventually make sufficient profits to cover the costs of servicing the loans, which means more spending. Similarly, if consumers spend less, not only do they have less need to borrow money, but also fewer sales happen, and therefore profits reduce, leaving businesses with less money to repay debts. So, like any profit-seeking business, lenders want growth.

It also works in reverse: lenders depend on growth to allow debt to be repaid, but growth depends on debt in order to happen.To understand this, some little known facts about profit need to be detailed…

Because prices include a profit margin (an amount over and above production costs), the amount of money distributed during production of goods – the payments made to do the producing and thus made available to consumers to spend – sums to less than the total prices of those goods. As a result, not all businesses can profit: even if consumers spend all of the money paid to them by producers during production, they can buy only some of the goods available at their profit-inclusive prices. If some producers sell at a profit, others – regardless of their efficiency – will necessarily not recoup their expenditure: either they will be forced to sell at a loss or they will stockpile unsold goods they might be able to sell later… except that they face the same situation then as well. So, ultimately, some will profit, others might recoup their costs with nothing to spare, others will lose.

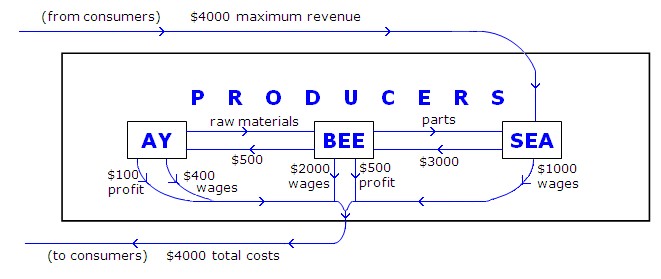

More detailed analysis confirms that not all businesses can sell all of their goods at profit-inclusive prices – the net profits for all businesses must sum to zero. The diagram below shows why. The three producers depicted can be treated as groups of different producers at the same ‘stage’ of production. For the period shown, ‘Ay’ and ‘Bee’ profit, but ‘Sea’, the producers of final consumable products, can at best recoup only their total costs – and only if workers spend all of the income they receive over the period, and Ay and Bee spend all of the profits they make over the period (their profits reducing to zero as a result). In this eventuality, some of Sea’s member businesses might manage to profit, but others must lose by the same amount.

On the other hand, if Ay and/or Bee retain any part of their profits (for investment or other non-consumption purposes), Sea’s members cannot even cover their costs – they make a net loss equal to the profits retained by Ay and/or Bee.

Of course, the economic flow also has purchasing power added to it via exports, government spending, and credit. But even if the total of these exceed the total money leaving the flow via imports, taxes, and savings, still they do not prevent losses, they only transfer or delay them. Exports merely redistribute between national economies, shifting the burden without adding purchasing power globally. Government spending also only redistributes. Credit, a more complicated beast, initially adds to the economic flow, but repayment of the debt with interest – by which lenders profit – ultimately siphons more back than went out, depriving other competitors of their chance of profiting…

When credit is provided to producers, they must set prices high enough to cover their costs, make a profit, and repay their debt and its interest. Hence, producer credit can be treated as one of the ‘raw materials’ of Ay or ‘parts’ of Bee, necessary for Sea’s production. But then, producer credit does not change the dynamics: still, whether funded by credit or not, businesses who profit (whether by making goods or by lending money) deprive others of doing so.

Credit provided to consumers, however, works differently: it adds extra money, originating from lenders (‘outside’ the producers’ box), to the flow passing to consumers. Enough consumer credit could even cover every producer’s profit (in theory, although consumer expenditure would never be spread so evenly for this to actually occur), but even then, this could happen only initially: repaying consumer debt requires eventually foregoing some other purchase, which again means that eventually not every producer profits, or else the consumer defaults on the debt and the lender fails to profit.

Inevitable loss can at best be postponed, by injecting consumer credit into an economy more quickly than debt repayments siphon it back out, but because this leads to a rising level of debt, and of repayments, it cannot forever delay the day of reckoning – inevitably, debt fails to mount, losses occur, and the delaying tactic collapses. (Sound familiar?) A snake trying to swallow its tail must stop sooner or later, if only to throw up.

It’s all intertwined – profits, growth, debt, each feeding on and dependent on the other – but without rising debt, economies will quickly suffer enough losses to thwart growth. Growth depends on debt. But when debt inevitably stops mounting at just the right pace, growth falters, profits slump, losses mount, and economies collapse.

All this follows directly and unavoidably from the profit-inclusive nature of prices: our economic game thus has instability in-built, a proneness to fall over sooner or later, which neither credit nor the obsessive-compulsive disorder of growth can prevent.

A few heretics advocate a no-growth or ‘steady-state’ economy, but this cannot be achieved if interest or profit is involved, because, as explained, they make losses inevitable, which gives any economy a tendency to contract: even if an economy did for a while achieve a steady-state, when, as tends to happen, productivity increases, less money would be distributed as wages to afford the same amount of or more output, which would cause contraction. Borrowing could compensate for reduced wages, but only temporarily, because paying back a loan with interest requires saving more than what the loan allows to be spent – so, the eventual effect would still be less spending. Mounting debt might maintain a steady-state, but even ignoring the impossibility of sustaining an appropriate rate of increase of debt, a steady-state with mounting debt is a contradiction in terms.

There is one possibility however. If jobs are lost as productivity increases, then total income obviously reduces – but so too do total costs, which makes it theoretically possible to reduce prices across the board by the same proportion as income. Similarly in reverse if productivity decreases. If prices and income move up or down in unison, then ‘all’ it takes to handle growth or contraction or a steady-state is to share the work around – for example, reduce average working hours in line with the amount of work saved (providing work for those who lost their jobs), and prices similarly. But of course, that wouldn’t allow profits to be maximised, nor would it increase labour market competition, nor would businesses condone their prices being adjusted to suit changes in other sectors, so it can’t be considered capitalism. But then it would all work much more easily and effectively without profit or interest anyway – neither requiring growth nor leading to inevitable loss – so why not go the whole hog?

Profit is over-rated, in any case, little more than a figment of hyperactive imaginations. Business reports of profits, however glowing, leave out many relevant costs and subsidies. One estimate of “only those costs which had been properly established by authoritative studies” suggested that “in 1994 corporations in the United States were permitted to inflict $2.6 trillion-worth of social and environmental damage, or five times the value of their total profits.”[5] Similarly, reported profits sometimes amount to less than that of government subsidies to business.[6] If properly and fully accounted for, perhaps no business would profit.

Surely it’s long past time to stop worshipping god the profit, the job and the holy growth, and instead adopt a non-compulsive economic system capable of stability and ecological care, and not dependent on the impossible goal of ever more.