It’s The Stupid Economy

Flawed beyond hope of repair, the dominant paradigm needs to be replaced.

Who could fail to notice the achievements of market economies? Even allegedly communist China has hopped onto the bandwagon. No wonder. Through market competition, successful nations – their most profitable competitors at least – have raised their standards of living sky-high, and faster than a speeding bullet, in the process doing away with many of the hardships that have defined human existence since we dwelt in caves.

Yet invariably this has been done with ever-present poverty amid plenty, ecological vandalism, mounting social stresses, and other problems that continue to undermine the achievements. Indeed, despite the avowed superiority of markets, even their most ardent defenders confess they occasionally fail – and in no small measure. Recently, an Economics ‘Nobel’ prize winner referred to almost one hundred economic crises in just the last quarter of the last century, “more frequent (and deeper)” than previously.[1] Similarly, when the 2006 Stern Report called the threat of climate change “the greatest market failure the world has seen”, the then Australian Federal Treasurer would not agree, pointing out that “we have seen market failures that have led to wars and famine and global poverty”.[2] With market enthusiasts like this, who needs critics? Clearly, markets spoil us for choice even as regards their own greatest failures and recipes for cooking our own goose: not just industrial-exhaust-led greenhouse steaming, but also ozone-depleted ultraviolet baking, deliberate or accidental nuclear barbecuing, chemical stewing, Peak-oil sautéing, population-bombed curing, and a host of other family favourites.

That something touted as so successful, and admired with not merely religious but often fanatical devotion, can also fail so abysmally demands explanation. The attempt that follows identifies fundamental systemic flaws that guarantee both success and failure. The flaws cannot be simply removed either, not without altering market competition so much as to render it a different system entirely, an outline of which is also provided.

Yes, I am going to dream on. As Peter Cadogan put it, “we need to know not just what to rebel against but what to rebel for.”[3] If you don’t entertain alternatives, then you have no choice – you’re stuck with the present. And I’ve seen the present – it doesn’t work.

Warning: cognitive dissonance ahead.

Rubbery Figures

Everything to do with money sounds absurd, unless one’s ears are tuned just right…

Our current economic and political games use ancient habituated rules. Their keystone is called the Law of $upply and Demand (L$D), which, according to economics textbooks, ensures that prices of goods and services function as accurate and meaningful market signals, so guaranteeing the most efficient use of resources and the most optimal of all possible economic outcomes. Yet this lofty claim, like so many in economics, depends on a plethora of unrealistic assumptions: uniform market prices for identical goods or services, no expenses for tracking down or delivering them, perfect foresight or no change, rising costs with the scale of production, and enough buyers and sellers to avoid any having enough market power to set prices.[4] Since the assumptions do not hold (as even a few economists admit), L$D-prices need not be accurate or meaningful, resources need not be used efficiently, and outcomes need not be optimal (which goes some way to explaining the excess of egregious market failures).

But then, how could L$D-prices be considered accurate or meaningful when they do not include costs avoided while pursuing profit maximisation – costs passed to the environment and society to bear: air, water, soil and noise pollution… soil erosion and salinity… desertification… reduced biodiversity… urban congestion and gridlock… diminished physical and mental health from over-work, under-work, and the stresses of economic competition… One estimate of “only those costs which had been properly established by authoritative studies” suggested that “in 1994 corporations in the United States were permitted to inflict $2.6 trillion-worth of social and environmental damage, or five times the value of their total profits.”[5]

Nor do L$D-prices take account of the direct and indirect savings to businesses that result from work done outside the official market economy by members of households and by volunteers – or even those resulting from the presence of roads, railways, ports, police, free or subsidised education, energy and communication networks, and much else paid for by governments (and sometimes handed over to private industry gratis). Let’s also not forget public-funded bailouts of ‘too-big-to-fail’ corporations – even, or especially, of those who most ardently chant that the market knows best and must not be regulated. Just the direct subsidizing of business by government through grants, tax breaks, incentive schemes, loan guarantees, wage allowances, investment rebates, and the like sometimes exceeds reported profits.[6]

But although many costs are excluded from L$D-prices, many others are inappropriately included, such as those of political lobbying… excess packaging… unduly lavish office furniture and equipment… prestigious petrol-guzzling company cars… exorbitant business lunches and dubious client entertainment expenses… jobs for the boys… Picassos and weekly lock-changes for executive washrooms… million-dollar consultancy fees for five minutes of pre-determined discussion with self-styled authorities long past their use-by dates… ‘brainstorming’ retreats and overseas ‘business’ trips that include five-star accommodation, century-old brandy, and Kama Sutra instructors… gambles that don’t pay off and other miscalculations… various other forms of waste, duplication, ego gratification and high living…

Rather than ensuring an efficient use of resources, L$D misleads us and wastes our time. One estimate[7] suggested only thirty percent of work in modern economies produces real wealth, the rest merely keeps us busy, such as by creating weapons of mass destruction then, after signing treaties, destroying them at fifty times the cost of production[8]… writing memos in quadruplicate full of inaccurate details about subjects of no relevance to people who aren’t interested… juggling paper profits… advertising… Another study of how abysmally the market allocates resources found that: “One half to three quarters of annual resource inputs to industrial economies are returned to the environment as wastes within a year.”[9]

And to achieve these very sub-optimal outcomes, L$D rewards necessary but comparatively easily supplied work to produce food, housing and clothing with far lower wages than non-essential work (or should it be called recreation) in art, music, sport, literature, film and TV. L$D also grants often offensively high payments for ‘labour’ in pen-pushing paper-shuffling bureaucracy, marketing, legitimised gambling, finance, post-15-minutes-of-fame speaking engagements, and other endeavours that produce no real wealth whatsoever.

But wait – there’s more.

Liquid Delusion

Instead of functioning as accurate and meaningful market signals, L$D-prices encourage delusion. With no more than the flourish of a pen, loaves-and-fishes banking systems lend money many times greater in amount than the savings left by depositors. Reserve Banks create money on receipt of nothing more tangible than government-completed forms. Currencies fluctuate, constantly shifting values based on perceptions, incessantly being bet upon, for and against. Creative accountancy manipulates ledgers to transform a reality of bankruptcy into a pretence of profit. Fickle manic depressive (sometimes paranoid) markets for bonds, stocks, derivatives, shorts, mortgage-based bundles, collateralized debt obligations, credit swaps, and various other too-clever-by-half exercises in self-deception – glorified IOUs and bets upon gambles – conjure up cash flows with almost as much ease as they lose them (the traders’ assumptions, biases and perceptions now enshrined in automated computer trading programs).

Modern financial exchange requires belief in order to work at all, otherwise it looks like sleight-of-hand. But do not expect rhyme nor reason, as it’s all based on perception. For instance, if the latest official estimate of inflation is calculated as a mere tenth of a percent more or less than the average anticipated by so-called authorities, then stock markets, interest rates or currencies can fall or rise out of all proportion. Or if a somnambulant federal treasurer casually includes the phrase “banana republic” while publicly speculating about his nation’s future, the currency can sink like a stone. Figments of hyperactive imaginations, L$D’s misleading numbers mean next to nothing – mean only what we perceive or choose to ascribe to them.

Nevertheless, the modern world is hooked on L$D, and so, deafened by the hallucinatory sound of money talking, we pursue profits and cash flows – not the satisfaction of needs. Money is mistaken for real wealth, and energies frittered accordingly. Lacking money and (consequently) demand, the poor cannot offer businesses any chance of maximizing profits, so their needs take a back seat to the mere desires of others. Work of great need is sacrificed in lieu of work that makes great profits. Mercedes are built for the Mercedes-less rather than homes for the homeless. Medical research panders to the vanity of the rich rather than curing diseases of the poor. The First World stockpiles mountains of excess food while the Third World starves.

Enough Is Not Enough

Yet official concerns are directed less at the quality of work being done than at the quantity of money exchanged. We are exhorted to focus our habituated L$D-competitive pursuit of profit and self-interest on the spending of ever more money, in order to buy more, to use more, to make more, to spend more to buy more to use more to make more to spend more… ever more. Economists call it growth. I call it an obsessive-compulsive disorder.

L$D-competition compels growth, because businesses that gain profits are obliged to invest much or all of them in new ventures intended to increase their profits, thus boosting production and spending, which equates to economic growth. If businesses don’t reinvest, they risk shrinking profits and ultimate loss, because either their markets will become ‘saturated’ with too many consumers already having purchased their goods, or newer products will supersede theirs, or they will be out-competed eventually by other businesses that do grow. So, the compulsion to grow is built into the game rules of L$D-competition.

But not only businesses have compelling reasons to want economies to grow, so do wage earners. If an economy does not grow, if instead its spending reduces, it has less need for production and work – and because less work almost invariably means less income, this causes obvious problems, not only for those whose income reduces, but also for the producers of the goods that might otherwise have sold if income had not reduced. Failure to grow thus encourages more of the same. Or, as Tim Jackson succinctly put it: “Growth is necessary within this system just to prevent collapse.”[10]

As well as businesses and workers, banks and other financial institutions have a vested interest in the creation of jobs and maintenance of growth: for loans to producers to be repaid, they must finance enterprises that eventually make sufficient profits to cover the costs of servicing the loans, which means more spending. Similarly, if consumers spend less, not only do they have less need to borrow money, but also fewer sales happen, and therefore profits reduce, leaving businesses with less money to repay debts. So, like any profit-seeking business, lenders want growth.

As long as populations keep growing, if prices do not fall proportionally, then more money will need to be spent to accommodate more mouths to feed, more bodies to clothe, more families to house, and so on. But L$D-competition compels us to aim to spend more even if populations do not increase – and it does so even though it operates in ways that, contradictorily, constantly reduce the need for spending.

When a producer raises their productivity – that is, when they produce more for the same or lower total cost, usually because of some technological advance or labour-saving invention – they gain an advantage over competitors by being able to sell at a lower L$D-price. But often this means fewer employees are needed – those who lose their jobs obviously have less income, so will spend less. Market saturation also reduces spending: many people might want to own an ‘iPay’, but once most have one, manufacturers will find it harder to keep selling them.

If economies functioned similarly to households or individuals, a reduction in the work required to produce and distribute needs and desires would be treated as welcome – the necessary work would be redistributed among all so that the average time spent working would reduce, and with less costs for producers, lower prices could mean reduced working hours need involve no loss of purchasing power. However, market economies cannot easily arrange this because they rely on competition – worker against worker, business against business. So when a business raises its productivity, its primary concern is not for the employees it will no longer need, but for its own bottom line: how much its profits will increase. A business threatened by market saturation will have similar selfish concerns: how to avoid its profits decreasing. Passing on the change to the wider economy via reduced working hours and prices would work against the bottom line.

And so, to compensate for reduced spending caused by raised productivity and market saturation, L$D-competition constantly requires new jobs and new goods and services to be created. Hence, we have built-in obsolescence to force buyers to upgrade their iPays to the latest version. And so, as lost jobs and saturated markets are replaced with new ones, more money is spent – the economy grows.

But the game has no finishing post.

So our options: to spend more money, so we can make more profits and repay more loans and create more work to replace jobs lost because of the way previous profits were increased, in order to earn more money and make more profits and create more work and repay more loans made to allow us to spend more money, so we can spend more money and make more profits and repay more loans and create more work, so we can spend more money… spend more money… more… more… more, you can do it for me baby, keep going, keep going, aaah, aaaaaahhhhh… uhh… eh?! Or, fail to grow: spend less, shed jobs, make fewer profits, repay fewer loans, suffer bankruptcies, financial collapse, recession, and the economy disappearing up its assets.

But no matter how many new jobs are contrived, no matter how much devotion and effort government and businesses put into keeping the treadmill ever rolling along, even with rising populations, economic growth inevitably falters and fails, every decade or so. Despite the shifting fluctuating values, the frantic efforts to constantly spend more, the relentless activity chasing phantoms in endless runarounds, the swirling liquidity, vortices sucking and gushing – inevitably the economic flow dilutes and evaporates amid recession.

Never Mind The Quality

Growth cannot be sustained indefinitely by its very definition. If we keep increasing our extraction of the top ten minerals by the modest three percent growth rate economies usually aspire to as a bare minimum, then in a thousand years we’d need to be digging up an amount weighing more than the entire earth.[11] Talk about digging your own grave.

To bypass this ultimate limit to growth, economies intent on constantly spending ever more could only hope to find ways of doing so by recycling a constant or declining supply of non-renewable raw materials, perhaps by expanding service and information industries. But even assuming that resource use can reverse its general tendency to increase,[12] a physical limit must be reached – especially when the global population eventually plateaus (estimated to happen mid-century) – as to how often and efficiently we can all research our family trees or have our hair cut or palms read or nails manicured or eat out. Even the modern economy cannot give us more than 24 hours in each day to consume.

However we attempt it, we pay a high price for trying to perpetually grow. Our arrested adolescent idée fixe about the thickness of our economic flow – quantity rather than quality – causes us to pay insufficient attention to how perhaps forty percent of paid work cleans up the mess made by the rest.[13] No wonder. To L$D-dazed eyes that can see only the short-term, the environment flaunts ‘free’ spoils – quick and easy loot – so, mother nature can hardly avoid being gang-raped and left to rot. (But she can be a vengeful mother.)

The aim of growth, and its concomitant goal of increasing profits, takes priority even when industries are thought to be fostering disaster – for example, various corporations continue to operate despite their massive greenhouse gas emissions. They are exonerated by widespread and dominant faith that ‘the market knows best’, that some of the profits gained will fund investment to eventually discover new ways to operate without the alleged ecological costs (such as by developing renewable alternatives). Some governments might try to hasten market progress by imposing carbon taxes and emission trading schemes which increase costs and add layers of complexity but do not directly change the methods in use nor the message: keep operating in ways seen as dangerous until you can eventually afford to figure out how to operate safely.[14] Keep doing things wrong until you can afford to do them right. Profit and growth first, all else second. If the same approach was taken towards thieves, they’d be allowed to keep stealing until they could afford to go straight.

Our worship of god the profit, the job, and the holy growth fosters not just abject stupidity, but also a universal dog-eat-dog mindset which alienates all and discourages civilisation. Consumerist (cannibalist) ethics ensure everything has a price. Us against them – all against all – thwarts community. Relentless L$D-competition transforms “I was just doing my job” into a universal excuse for collective idiocy – even bestowing clear consciences to exporters of hi-tech weaponry and torture equipment banned in the exporting countries, yet sometimes sold even to nations rife with human rights violations and/or links to terrorism.

No wonder that pessimists and doomsayers, often obsessed with ecological and social decay, claim growth must not only falter but eventually shift into long-term reverse, the day of reckoning arriving any time soon. Of course, optimists and zealots, often infatuated with technological achievement (‘techno-optimists’), insist we can grow forever. But both groups make the mistake of extrapolating short-term trends into the future: usually very short-term downwards trends of a few years in the case of some doomsayers, somewhat longer upward trends of decades for most optimists. Both miss not only fluctuations hidden within the trends but also problems inherent in the game itself.

Losing The Game

Modern civilisation has a systemic problem, and no amount of tinkering or changing the window dressing (reformed financial regulation, new tax rules, another merely alleged free trade agreement, etc) will suffice until and unless the fundamentals are changed. It would not even suffice to somehow abandon growth if we still continued to compete for profits and jobs. Even if everyone somehow managed to compete with maximum efficiency, still none can win a competition without others losing…

Most economics textbooks usually include, early on, a figure depicting the ‘circular flow of the economy’: businesses pay money to their workers, who use their earnings to buy the goods and services produced. The money that flows out from producers to consumers returns (unless some of it is saved). But this (too) simple overview hides the obvious: because prices include a profit margin (an amount over and above production costs), the amount of money distributed during production of goods – the payments made to do the producing and thus made available to consumers to spend – sums to less than the total prices of those goods.

As a result, not all businesses can profit: even if consumers spend all of the money paid to them by producers, during production, they can buy only some of the goods available at their profit-inclusive prices. If some producers sell at a profit, others – regardless of their efficiency – will necessarily not recoup their expenditure: either they will be forced to sell at a loss or they will stockpile unsold goods they might be able to sell later… except that they face the same situation every cycle of the flow. So, ultimately, some will profit, others might recoup their costs with nothing to spare, others will lose.

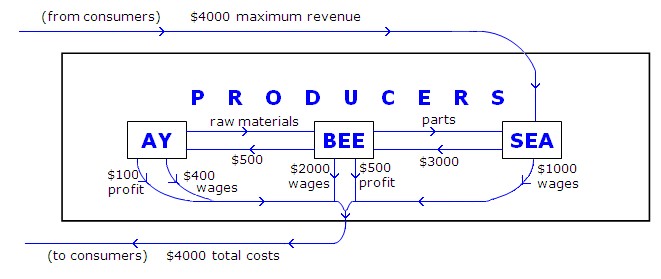

More detailed analysis confirms that not all businesses can sell all of their goods at profit-inclusive prices – the net profits for all businesses must sum to zero. The diagram below shows why. The three producers depicted can be treated as groups of different producers at the same ‘stage’ of production. For the period shown, ‘Ay’ and ‘Bee’ profit, but ‘Sea’, the producers of final consumable products, can at best recoup only their total costs – and only if workers spend all of the income they receive over the period, and Ay and Bee spend all of the profits they make over the period (their profits reducing to zero as a result). In this eventuality, some of Sea’s member businesses might manage to profit, but others must lose by the same amount.

On the other hand, if Ay and/or Bee retain any part of their profits (for investment or other non-consumption purposes), Sea’s members cannot even cover their costs – they make a net loss equal to the profits retained by Ay and/or Bee.

Of course, as textbooks eventually admit, the economic flow also has purchasing power added to it via exports, government spending, and credit. But even if the total of these exceed the total money leaving the flow via imports, taxes, and savings, still they do not prevent losses, they only transfer or delay them. Exports merely redistribute between national economies, shifting the burden without adding purchasing power globally. Government spending also only redistributes. Credit, a more complicated beast, initially adds to the economic flow, but repayment of the debt with interest – by which lenders profit – ultimately siphons more back than went out, depriving other competitors of their chance of profiting…

When credit is provided to producers, they must set prices high enough to cover their costs, make a profit, and repay their debt and its interest. Hence, producer credit can be treated as one of the ‘raw materials’ of Ay or ‘parts’ of Bee, necessary for Sea’s production. But then, producer credit does not change the dynamics: still, whether funded by credit or not, businesses who profit (whether by making goods or by lending money) deprive others of doing so.

Credit provided to consumers, however, works differently: it adds extra money, originating from lenders (‘outside’ the producers’ box), to the flow passing to consumers. Enough consumer credit could even cover every producer’s profit (in theory, although consumer expenditure would never be spread so evenly for this to actually occur), but even then, this could happen only initially: repaying consumer debt requires eventually foregoing some other purchase, which again means that eventually not every producer profits, or else the consumer defaults on the debt and the lender fails to profit.

Inevitable loss can at best be postponed, by injecting consumer credit into an economy more quickly than debt repayments siphon it back out, but because this leads to a rising level of debt, and of repayments, it cannot forever delay the day of reckoning. Although debt often does rise, for years at a time, every recession proves this cannot be sustained. Inevitably, debt fails to mount, losses occur, and the delaying tactic collapses. (Sound familiar?) A snake trying to swallow its tail must stop sooner or later, if only to throw up.

So, the goal of profit, however it might motivate innovation, productivity and activity, guarantees loss for someone, somewhere, sometime or another. Hardly surprising really: whoever heard of a competition in which everyone wins? Competition means someone has to lose. But with our current economic rules, someone has to lose, regardless of their efficiency – yet another reason why the standard arguments for optimal outcomes and the efficiency of free markets founder.

The Modern Economy & Other Disorders

Starting to feel the cognitive dissonance? If so, you might be about to object that economic growth, the eternal saviour, must put things right. Afraid not. This is not some technical issue, or some fault in economic science. We are talking about a critical systemic failure, one that cannot be properly fixed without abandoning profit and interest. It stems not from how much is spent, but how it is spent. Winners’ reinvested profits boost spending and growth, but losers have the opposite effect: their diminished expenditures, like those of any employees they consequently shed, reduce potential profits for others, retard growth and encourage recession. To achieve net growth, either debt or net aggregate profits are required, but the latter can only happen via mounting consumer debt. So, growth, like net aggregate profits, depends on continuously creating more debt than is repaid – on debt always mounting, and at just the right pace. When this inevitably fails to happen, growth falters, profits slump, losses mount, and economies collapse.

As all this follows directly and unavoidably because of the nature of profit, the dynamics of competitive market economies make them inherently unstable, prone to fall over sooner or later – and neither credit nor the obsessive-compulsive disorder of growth can prevent it.

In addition to this fundamental problem, because winning the economic game increases the chances of continuing to win, and likewise losing fosters more losing, wealth tends to concentrate, and inequality generally increases.[15] And because competition to maximise profits usually results in costs minimised or avoided – via production methods that erode, deplete, pollute and/or in some other manner degrade the environment – the rules of our economic game not only guarantee instability, poverty, and inequality, they also all but assure ecological degradation.

Economic theory – as usual by adopting many assumptions that are often not valid, and assuming many conditions that are often not met – has claimed that competition in a free market causes the most efficient to succeed, while the lazy or incompetent or inferior are out-competed and fall by the wayside. With this view, losers have no argument to make, they simply aren’t up to the job, and winners deserve their success. Losers will just have to wait, as they have for centuries, for the wealth to ‘trickle down’ from the winners. It could be redistributed by governments but (unlike corporate subsidies and bailouts) that would be interfering with the infinite wisdom of the market. Belief in this dogma exonerates the conspicuously successful from feeling any guilt while allowing the biggest losers to be ignored, since they clearly deserve their fate.

Yet the preceding analysis forces the opposite conclusion: that economic success need not follow necessarily from efficiency, discipline, skill, or any other advantage – nor failure from their lack. It more resembles a lottery. The ideal that anyone with an idea and perseverance can prosper sounds enticing, but you can do everything right and still, if someone else does it with more luck, you will fail simply because not all can win. Even if you win for a while, every winner always retains a chance of joining the losers: you could fail through no fault of your own when the next recession hits – and recessions happen inevitably when the rules ensure that someone is losing and/or going into debt all the time. In economies ruled by competition for profits, there can be no security for anyone, and no guarantee of efficient let alone optimal outcomes or resource allocation.

Less Is More

How’s that cognitive dissonance going? It will probably increase as you read on, but perhaps a brief recap will help…

By adopting many unrealistic assumptions, economists have claimed that market prices function as accurate signals for the assignment of resources and so lead to optimal results. But this ignores the inherent inaccuracy of prices… their exclusion of many relevant costs (such as ecological, social, government)… their inclusion of many other unwarranted costs (mostly waste and excess)… the delusional manipulations of financial flows which cause money to be mistaken for real wealth… and how the pursuit of profit causes work of great need to be ignored unless it looks lucrative. The inclusion of profit in prices also means someone has to lose – somewhere, sometime or another – regardless of their efficiency. Increasing debt delays but doesn’t prevent this, because lenders pursue their own profits. And spending more to pursue economic growth also proves no help, because it only provides more of the same. Instead of guaranteeing optimal outcomes, inaccurate profit-inclusive L$D-prices make our economic game unstable, prone to fall over sooner or later, while all the time wasting resources, subjecting its players to a lottery, assuring poverty and inequality, and all but assuring ecological degradation.

Yet the economic rules that compel this counter-productivity, and the self-destruction it may be leading us to, are not god-given, self-evident, unalterable commandments. They have become entrenched due to historical accident, so ingrained from long use that alternatives may evoke cognitive dissonance, but they remain arbitrary.

Perhaps we have grown too used to it all to consider changing, too habituated to recognise the addiction. But I am going to dream on. Instead of the profit-mad economic flow and its deranged rules, I will describe another more balanced, calmer, more controlled arrangement, one at our beck and call, with better rules more suited to modern times, needs and abilities, and more capable of providing a truly sustainable and attractive future.

We don’t need ever more of the same as techno-optimists hope. And we certainly don’t want the disasters of insufficiency envisioned by doomsayers. Yet we do not have a choice only between ever more and dangerously less. Rather, we need to find a balance. And to achieve that, we need economic (and political) systems that allow us to organise and ensure enough, yet able to cope with fluctuations above or below expectations or ideals (rather than falling in a heap each time we don’t spend ever more).

Understanding those systems may not be easy because they will seem alien. So you’ll probably need to read the following at least twice, once to take in the parts separately, the second time to see the big picture to which they sum.[16]

Stability

To a large extent, we’ve been doing it backwards, horses dragged behind runaway carts. Our current economic rules compel us to spend ever more – actions and decisions are then made subject to that compulsion, with much harm and inefficiency resulting. To avoid that, we need to construct new economic rules that don’t compel ever more activity, but which ensure that only work of genuine need or sufficient desirability is paid for, that all such work can be afforded, and that no-one is penalised whenever less (or more) work is needed.

Suitable rules have already been hinted at when discussing growth: a reduction in the work required to produce and distribute needs and desires should be treated as welcome, it should cause the necessary work to be redistributed among all so that the average time spent working reduces – and with less costs for producers, prices could also be lowered so that reduced working hours involve no loss of purchasing power.

This can be arranged most easily by abandoning profit and interest – perhaps the greatest sources of instability in market economies – and by keeping wage rates static.[17] Such radical changes can be justified by explaining the considerable advantages they provide…

Consider an economy of any size over (say) a week during which it’s expected to neither grow nor contract: production won’t change, and everyone keeps their jobs and consumes as normal. Production costs for such a stable economy over the week are known in advance: without interest or profit, total producer costs equal total wage costs (either paid directly to the producers’ employees, or indirectly to those of other producers, as the figure above demonstrated). Hence, without profit or interest, the total prices of the goods produced over the week can be set to equal the total production costs.

Of course, expectations are not always met. So, at the end of the week, it makes sense to examine what actually happened, what work was really required, especially the time needed to do it. If less work was needed by some producers than anticipated and paid for over the week, then average working hours for the entire economy can be reduced accordingly for the next week – with the necessary work shared. But if the total costs of work reduce, so too can the total prices of the goods produced by that work – by the same proportion.

This approach – Cost And Price Equalisation (CAPE) – has the main effect of absorbing changes which now give rise to the boom-bust business cycle into altered working hours and prices. If efficiency improvements and/or sales declines and/or reduced consumption and/or anything else decreases the need for work by x percent, the same work is shared over a working week also lowered by x percent. Income and total costs then also reduce by x percent, because of which, CAPE requires an x percent reduction of all prices. Similarly, more shared work, whether because of reduced productivity, natural disaster, or any other reason, causes the working week, income and prices to all rise by the same proportion.

So, though people can get less (or more) income, none lose (or gain) purchasing power because all prices drop (or rise) by the same proportion as income.

A One-Day Working Week

Because CAPE prevents people from being penalised for finding ways to save work, it allows work to be minimised: gradually, we could automate as much as possible, abandon the seventy percent of work currently performed in developed economies that produces no wealth, and build to last instead of to obsolesce – eventually, we could do only work that is really needed and wanted. (The shock of adjustment for people doing work identified as unnecessary could be minimised if they are paid the same wage to be retrained for other useful employment, with retraining payments included in CAPE calculations.)

If developed economies do only the thirty percent of current work really needed, then CAPE ensures we will have prices much lower than today’s, and a working week of only about a day and a half!

Of course, the less people work, the less resources (like petrol, tyres, steel, concrete, paper) are needed for that work, and the less pollution, congestion, waste and other damage caused, so the working week could shorten further. But we must also consider whether much work that isn’t now done really should be.[18] In the short term at least, these opposing concerns might well balance out, but in the medium term of perhaps a decade or so, as we learn to produce and consume more sensibly and responsibly, we could well end up with a one-day working week.

Not everyone need work the same hours of course. Those whose work cannot easily be performed in a single day per week can work longer hours but (hopefully) over compensably shorter working lifetimes. An economy might have so few doctors, for example, that each needs to work (say) five days a week, until more are trained to ease their burden and allow them to return to standard hours – but then their extra initial contributions would be compensated by subsequent reduced hours and/or earlier retirements. This complicates CAPE, but given sufficient computer resources and organisation, it almost certainly poses far less trouble than what now goes into calculating GDP.

Attitudes & Motivation

Gasp, shock, horror! An end to profits!? Job sharing!? Static wage rates!? A one-day working week!!? Impossible! Disastrous! What would motivate people? How could they cope with all that spare time? Idle hands make the devil’s work. Harrumph.

Yes, yes, heard it all before. Protestant work ethic and all that, flowing from the belief that human nature is fundamentally competitive and our economy merely reflects this. But this belief has it back to front.

To a dominant extent, ‘human nature’ is determined by the specifics of ruling institutions and societal conventions, not vice versa. Change the economic game and ‘human nature’ alters too. For example, the practice of Soviet Socialism moulded the ‘nature’ of its practitioners, but when Eastern Europe’s centrally planned economies converted in the 1990s to ‘free’ markets, many once docile, unquestioning followers turned into aggressive demonstrators, coup defeaters, and profit-hungry capitalists. Anthropological studies of other cultures also demonstrate that a competitive ‘nature’ is neither natural nor mandatory. Nicobar Islanders play (or played) sports without starting points or winning posts, full of strenuous competition, but only until one side gains a significant lead, after which they ease off and allow the opposition to take the lead… for a time. Trobriand Islanders grow(or grew) yams to excess, their social conventions demanding they keep about a quarter and give most of the rest to in-laws. Agree to define any set of conventions, institutions and/or economic game rules, and ‘human nature’ changes accordingly.

Profits and rising wages are now seen as fundamental only because of habituation to long-used (stale) economic rules. Their allure will disappear under an arrangement that guarantees what they are now supposed to enable: affordability, stability, and more leisure. Neither need a shorter working week without any loss of purchasing power spoil people, destroy their incentives, or encourage hedonism and anarchy. We will still need to use our time productively, spurred on by other – better – motivations than higher wages and profits, reasons far more sustaining and ‘natural’ than the current ‘need’ to work: reasons such as the urge to avoid boredom and to feel useful and valued (or, if you prefer, to satisfy and please others)… the thrill of achievement... self-development and the hope for immortality through exceptionality… and the satisfaction of basic needs and desires. Indeed, vastly increased spare-time should unleash rather than quell our potentials, and inspire greater creativity.

The goal of arranging a fairer saner economic system that allows all people to prosper should provide sufficient motivation in itself – a truly worthy goal capable of serving (in the words of JFK’s speechwriter) “to organize and measure the best of our abilities and skills”, much more so than did the mostly technological achievement of a lunar landing.

Determining What’s Needed

Nevertheless, the idea of sharing all necessary work probably evokes clichéd fears of socialist planning – fears that are not warranted. Figuring out what work – public and private – is really needed and wanted, and ensuring it suits priorities appropriate to circumstance and culture, cannot be left to central planning by faceless bureaucrats and party apparatchiks, any more than it can to profit-obsessed CEOs and marketing managers.

The task can be considerably eased by the adoption of a bottom-up decentralised participatory form of online democracy underpinned by small self-governing electorates arranged into progressively larger associations whose decisions require the majority agreement of constituent groups – this is detailed later (beginning in the section Plurocracy). While specialist co-ordination and advice at times will be needed, especially regarding the latest innovations, newly invented products, and availability of resources, mostly requirements can be determined and fed into an online database at the base-electorate level by the people themselves, then tallied and tabulated at successively higher levels, up to (and for some concerns even beyond) the level of a nation.[19] Such a market surrogate enables needs and desires for goods and services (and provision of labour) to be identified and accrued from the bottom up, assisting producers and workers to plan and employ resources accordingly.

Once the necessary work is identified, co-operatively sharing it is assisted by the same online mechanisms, with people nominating themselves for specific work. Personal choice, needs, skills, dispositions, and experience – as well as practicalities such as location and transport availability – should continue to play the dominant roles in determining who gets what work. However, people are always going to see some work as odious or undesirable, and it seems unreasonable to expect a cooperative society to require those jobs to be performed by an unlucky few. Rather, true cooperation requires all to take on an equal small share of work that none or too few want to do. Once established which work lacks workers, people can choose which of the unwanted work they prefer. But probably still some work will lack sufficient volunteers, and have to be assigned – perhaps most fairly by periodic randomisation, subject to the constraints of spreading the load evenly, and not forcing people to work impractically far from home or to do labour for which they clearly have no suitability (for example, abattoir work for vegetarians). Even then, volunteers’ online recording can indicate they prefer to swap or give up any assigned work to others less repelled by it. Certainly, hard and fast draconian solutions need not be imposed, but all willing participants need to be prepared to compromise to some small extent – the advantages that flow from doing so should provide persuasive enough arguments to ensure it…

Affording What’s Needed

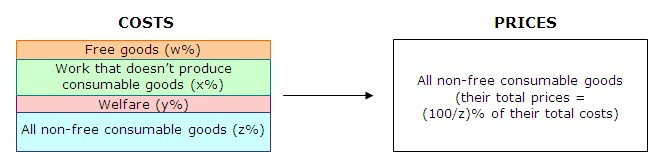

Although CAPE balances total costs with total prices, the price of any individual product need not equal its cost.

Given a choice, people might indeed prefer some goods to be made free – housing, education, health care, a reasonable minimum yearly quota of staple food and basic clothing, and perhaps more. Also, some work definitely needs doing but does not directly result in finished consumable goods, such as environmental regeneration and repair, construction of community facilities and public roads, international development and aid, and the less dysfunctional work of governments such as welfare for the disabled, retired, injured, and anyone genuinely unable to work.[20]

With CAPE, any product can be made free, and any worthwhile work that does not produce consumable goods can be afforded – simply by increasing the prices of all non-free consumables by the appropriate proportion. As the figure below shows, these costs, in effect, are ‘absorbed’ into the prices of all non-free consumables. (Yes, Virginia, there really is such a thing as a free lunch.)

No, this approach does not lead to outrageous prices for consumables: CAPE’s balance between total costs and total prices ensures all goods can be afforded by definition. Consider too: if you don’t pay anything for your most fundamental needs like housing (including mortgages and rent) and basic food and clothing, you have less to spend on, and a much greater disposable income – especially if you don’t pay taxes (directly at least, since their equivalent is absorbed into the prices of all non-free consumables). Even if prices of non-free goods exceed those now current, so too will your capacity to afford them. But prices will probably decrease compared to now, because if the working week is substantially reduced to include only useful work, then CAPE requires the reduced costs to be balanced by similarly lower prices. Keep in mind, too, that if any product starts with a low price relative to others, it stays relatively low, whether prices rise or fall in line with the working week.

Of course, disasters might prompt increased work, an aging population might push up working hours and prices, and other factors might have similar effects, but no system can guarantee a constant utopia. CAPE, however, provides a mechanism for dealing efficiently and fairly with any potential disruption.

So, with CAPE, no longer does the question ‘what can we afford?’ take priority, but rather ‘what do we need?’, and ‘what do we want that we’re prepared to work for?’

Stewardship

The possibility of free housing may evoke thoughts of socialism and collective ownership. I have something else in mind – and not just for housing.

Like staple food and other free goods, the costs of developing land for use, and building homes and fixed capital such as factories, can be CAPE-absorbed into the prices of all non-free goods and services – in other words, land, homes, and fixed capital can be made free. Doing so renders stocks, bonds, and other destabilising speculative money-raising devices, as well as mortgages and business loans, (deservedly) obsolete.

It can be afforded quite easily. The costs of fixed capital are now already absorbed into prices (or at least are meant to be). The costs of housing – less than ten percent of current national spending – require only a similar increase to prices in order for housing to become free (and most people now spend several times more than ten percent of their income on mortgages or rent).

Unable to be acquired by a highest bidder, free land, housing and fixed capital need not be owned (nor rented), but instead plurocratically stewarded…

People living in the smallest plurocratic electorate with borders fully enclosing unused land steward it. They have responsibility for looking after the land until they agree on how, if at all, to use or develop it, with larger principles and interests protected by the plurocratic decision-making process (see the section Decision-Making).

Home stewards have all the usual rights bestowed by ownership, except they cannot sell (or buy) their houses. Responsible home stewards simply move house – the more responsible their stewardship, the greater their options. Computerised waiting lists assist the process by allowing people to nominate houses and/or areas of most interest to them.

Fixed capital is stewarded mostly by the people operating it – all the workers of a factory, for example – but also, and ultimately, by those most directly affected by the capital’s operations: those living in the smallest plurocratic electorate with borders fully enclosing the capital. Such an arrangement encourages ecological and social care, which CAPE ensures can be afforded.

Accounting For What’s Needed

With CAPE, not only is the pursuit of profit abandoned, and businesses stewarded rather than owned, but individual producers do not even have the capacity to set or alter prices of their goods. Some even have to accept that their goods are sold for free. But all of this can be handled easily enough if…

Every producer has a CAPE account, credited at the start of each CAPE period, say a year, with an amount that fully covers their expected expenditures for the work planned to be done by them. When a good or service is purchased, the account of the purchaser is debited by the price, but the account of the producer of the good or service is credited with the cost of producing what was bought.

Over the year, some producers undoubtedly spend more or less than they expect, or sell fewer goods,[21] or suffer shortfalls – so by year’s end, their accounts differ from at the start, thus providing data to inform future allocation of work and resources. Nevertheless, at year’s end, producer accounts are reset to zero then re-credited for the next year’s expected expenditures.

Similarly, ‘project’ accounts for work that does not produce consumable goods (such as housing construction or factory building) function like producer accounts, except they involve no purchases of produced goods. If, for example, a new energy system needs to be implemented within a decade, its anticipated costs for that decade can be balanced with all other anticipated costs, and absorbed into the prices of all goods to be produced over the decade. At the beginning of each year, the project account is credited with its expected costs for the period. As work done on the project is paid, its account dwindles, but at the end of every year until the project is completed, the account is reset with a credit sufficient to cover its anticipated expenses for the following year. Any differences between the final figure at the end of each year before re-setting the account is used to assist better subsequent planning, but these ‘discrepancies’ have no more significance than that (except perhaps for pride or shame if planning consistently proves accurate or not).

Similarly, each worker is credited their full year’s income at the start of each year, and welfare recipients likewise (or this can be done weekly, fortnightly, or monthly). As people spend, their accounts dwindle. But unlike producer and project accounts, those for consumers are not reset to zero at the end of each year, rather they accumulate, so functioning as statements of each individual’s overall contribution to their community. Hard workers and frugal spenders keep their accounts mostly in credit. Big spenders and lazy burdens, on the other hand, have accounts more often in debit.

With this arrangement, all forms of money-lending and interest can be abandoned, as well as superannuation.[22]

Encouraging Responsibility

“Unrestricted credit!”, I hear some cry in utter exasperation. So what would stop a person from simply refusing to work at all, yet still spending like a millionaire? Even if those who deliberately and consistently choose not to contribute receive no welfare payments, they could still run up unlimited debts.

I suggest few people would abuse a system built around cooperation and sharing of both the work and the fruits of that work, especially with community approval likely to play an even more significant role than it does now. Those who did fail to pull their weight would likely have personality problems of a scale that would make them difficult for any system to handle. However, probably few could persist for long without ending up shunned by their communities – which might well change their minds. Most people, however, would instead feel liberated – not just by stable economic conditions, and the abolition of any need to compete, but perhaps most by the absence of compulsion. They’d be motivated to make a responsible choice because they could do so without coercion. And we’re talking, remember, of eventually only one day’s work per week. So, probably, most people would keep their accounts in approximate balance from one year to the next.

Nevertheless, while no one would be forced to work, they can still be encouraged in different ways to do the responsible thing. The most obvious encouragement stems from the knowledge that if enough people take the lazy option, too few people are left to do the necessary work, and then everyone suffers. Co-operation can be further, and more inventively, encouraged if anyone refusing work for more than a year (or with an account in debit beyond a plurocratically agreed value) is disallowed moving house except to a place of lesser value than their existing residence (the longer they refuse to work, or the larger their debit, the less the quality of housing they can choose). Similar encouragement follows if everyone’s account balance is made public information at all times (even after death), freely available online and accessible to anyone desiring to see it (likewise for producer and project accounts). Having everyone’s final account balance displayed on their gravestone or memorial plaque also seems likely to motivate most people to avoid an unflattering epitaph. As a last resort perhaps, anyone refusing to work for a long enough period might have their plurocratic voting privileges revoked until they started putting in a reasonable effort.

Stable Money

Some readers might object to the rubbery and manipulated figures produced by CAPE. But that misses the point. As previously explained, L$D has inspired plenty of the same. Money can be accepted and used only if there exists a common acceptance of utterly artificial definitions of its ‘value’, its means of creation, and its purpose. Make no mistake: we do have a choice as to which definitions to use. As occurred for example in Germany after its runaway inflation of the early 1920s, if people grow convinced firstly of the usefulness of new definitions, then of their necessity, they will become part of the social fabric, woven tightly enough not to risk immediate unravelling. We have great need for new definitions, because accustomed definitions are wasting and threatening our lives. CAPE’s definitions offer many advantages.

For example, with CAPE’s accounting of expenditures, and without money lending, mortgages, compound interest, superannuation funds and the like, banks and financial institutions cannot collapse and savings cannot disappear into thin air. And with wage rates essentially fixed (alterable only when plurocratic agreement determines that circumstances have changed enough to make any existing wage rates misrepresentative of the value to the community), it becomes possible to assign currencies fixed ‘labour standards’. One dollar can be defined as the payment for (say) five minutes of carpentry, three minutes of medical care, six of farming, or any combination of these and/or other labours.

Definitions might differ from one nation to the next, but an average of all national standards – a global ‘composite-job’ – can determine international exchange rates (not to mention an international currency). For example, if Australia pays $4 for ten minutes of the composite-job, and the USA $3, then the Australian dollar has the same value as three-quarters of a USA dollar. No more energies squandered on currency speculation.

Fair Trade

Although it makes sense for all nations to aim for as much self-reliance as possible, some nations will always find it much easier to produce certain goods and services than others – not much chance of growing pineapples within the Arctic circle, for instance. So CAPE has to cater for exports and imports.

For consistency with CAPE’s overall approach, the costs of imported goods need to balance (and so be afforded by) the prices charged for exports. However, inevitable imbalances (current account surpluses or deficits) need prompt nothing more inconvenient than altered working hours to restore balance: longer hours to increase exports, shorter to reduce them. If so handled by CAPE accounting, international trade need not require any exchange of hard currencies.

Only when a large national surplus or deficit persists does a problem exist, but this seems unlikely to occur in a co-operative world unless as a result of differing levels of development between nations. To discourage this, to ensure that appropriate technology and other means to produce goods are made available to all, to help develop the poorest nations (though not to the level of the worst excesses of the developed world, which is probably not even possible), and to relieve incipient international tensions (and motivations for seeking refuge in other countries), exports to poorer nations can be discounted.

Say, on some measure of relative wealth, Australia rates 9 (out of 10), Turkey 5, and Liberia 1. Australian goods can be sold to Liberia for 1/9th of their cost, or to Turkey for 5/9ths. Liberia can buy Turkish goods at 1/5th cost. To buy a $90 Australian product, for example, Liberia debits its CAPE-trade account by $10 in favour of Australia, which credits itself with the discounted $80. (Credit itself! Harrumph! Outrageous! Don’t forget, the rules can be chosen – why not replace troublesome old habits with new methods that serve a desirable purpose?) This process of Poor And Rich Exchange (PARE) offers an alternative to the currently popular RAPE.

Democracy

All of the preceding economic proposals are advantaged by an equal revitalisation of political arrangements.

The word democracy comes from two Greek words: demos, meaning people or population, and kratos, meaning power. So, democracy means people power – government by the people… at least in theory.

In practice, modern ‘democracy’ provides people not with the power to govern themselves, but with inadequate options between often misrepresented party devotees who, once elected, effectively run society (occasionally into the ground). Not choice but the relinquishing of choice, and the abdication of responsibility.

Power is not the sole province of ‘representatives’ however. It’s also shared by a few outside government: dominating contemporary ‘democracy’, mutually masturbating coalitions of political and economic forces constantly shift and realign as they overtly and covertly tussle for control. But although the elected and the elect may swap or share puppet and puppet-master roles as circumstances change and interests overlap or diverge, the concentration of so much power in so few hands prevents any possibility of true democracy.

Democracy also fails because of its one-size-fits-all approach. Many democracies elect political parties or squabbling coalitions with bare majority support. Neighbouring electorates often have diametrically opposed voting patterns. Yet governments claim mandates or consensus despite a clear and obvious plurality of views.

Plurocracy

To avoid the failures of ‘democracy’, a bottom-up decentralised participatory system is needed, underpinned by small self-governing electorates arranged into progressively larger associations whose decisions require the majority agreement of constituent groups.

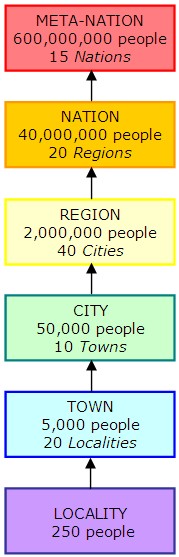

Call the arrangement plurocracy (since it correctly assumes a plurality of views), and base it on electorates called localities, each consisting of (say) 250 people (perhaps 200 old enough to vote).

Groups of (say) twenty localities form electorates (of 5,000 people) called towns.[23] Groups of towns, in turn, form larger electorates – groups of these, still larger electorates – and so on, with the biggest varying in size to suit population densities, ethnic and religious groupings, state boundaries, and other factors. To illustrate the idea (as in the diagram at right), ten towns might form a city (50,000 people[24]), forty cities might form a region (2,000,000); twenty regions, a nation (40,000,000); fifteen nations, a meta-nation (600,000,000); and ten meta-nations, the world. Something like that.

Decision-Making

With plurocracy, decisions are not abdicated to representatives, but made by the people themselves – for any and all issues with which they wish to be involved. (Representatives still serve a role, however, as the next two sections explain.)

Decisions are made from the bottom up: for any electorate to plurocratically pass any proposal requires approval not only by a majority of the electorate’s voters but also by a majority of the electorate’s constituent electorates – each, in turn, approved also by a majority of their constituent electorates – all the way down to the locality level.

Plurocratic electorates at every level function semi-autonomously. Although each locality, for example, must heed the plurocratic decisions of its town, these apply only to issues affecting two or more localities (such as construction methods or building height restrictions). Each locality makes its own rulings for purely internal affairs (such as where to build a new house or shop, though recommendations for this might be made by its town or city).

Importantly, each electorate has the right to secede from its ‘parent’ electorate. If, for example, a locality found itself often voting against decisions plurocratically passed by its town, and felt enough dissent, it might choose to secede from its town, and join other more-like-minded localities (not necessarily with common borders) or else become independent.[25]

Electorates might even determine their own definitions of ‘majority approval’ or vary it according to the issue, or seek consensus by modifying proposals until they satisfy all who previously dissented. Some might ‘weight’ votes in certain circumstances, so people most affected by decisions have the greatest say. Others might vote on a scale of (say) 0 to 100, with a pre-agreed average or median score required for any decision to be passed.

Of, By & For the People

By whatever method they choose, each locality selects its representative from one of its own voters – most probably by voting for him or her, or by selecting different representatives for different issues, or by rostering representation among volunteers. Whatever the method chosen,representation is not faceless or unaccountable in an electorate of two hundred voters.

Similarly, each town selects their representative from their constituent localities’ representatives, or maybe the localities’ representatives make the choice, with town reps perhaps replaced or assisted at the locality level. Likewise for higher levels.

And so, ‘government’ at any level consists of all the elected representatives of that level, not simply those able to form a majority based on their affiliations with political parties. Indeed, given the bottom-up process of plurocratic decision-making, political parties seem more likely to impede true independent representation than assist it, and so might be best avoided.

Representation

Representatives have mostly coordinative roles, providing or disseminating options and proposals to their electorates, and making sure they have all available and necessary information to make up their minds.

Much less complacent representation than occurs now can be further encouraged by storing the votes for all levels’ representatives online, each vote accessible to its owner to change any time he or she wishes. This saves the cost and tedium of periodic elections. And because power remains with the people, any change of representation merely means voters have changed their minds, not a potentially destabilising power shift.

To assist representatives and their electorates, the online voting system can also be used to register anyone’s opinion on any issue requiring a decision, seek and obtain ‘expert’ advice, bring any issue to the attention of those it affects, function as an electronic communal noticeboard, and allow any vote on any decision to be altered as voters plurocratically change their minds. True democracy from the comfort of your favourite armchair, with people self-governing – proposing, deciding, and implementing their own schemes whenever possible, advised by ‘experts’ when unavoidable, and coordinated by each level’s representatives directly answerable to their electors. (This probably provokes more hands upraised in horror: How can people be trusted with so much power? They’re bound to abuse it. Yet this attitude, provoked by historical examples of people with excessive centralised power, misses the point: problems are created by concentration of power, not the sharing of it. Ask any parent: a child only learns responsibility when they are given it. Similarly, adults won’t learn political responsibility until they are given it.)

Rights & Duties

Of course, even with plurocracy and the right to secede, agreements could discriminate against minorities, and perhaps even formalise persecution. To avoid this, people must participate with vigilance, and be educated from an early age to understand the responsibilities associated with self-determination.

To this end, I propose a simple overarching guideline: everyone has a right to do as they see fit, as long as their choices fulfil the duty not to harm others in the process. Of course, no guideline is foolproof. Care must always be taken to distinguish the truly harmful from the merely disagreeable – to avoid misinterpreting due to shocked sensibilities or outraged ‘morality’ (or laziness). And because even a majority definition of ‘harm’ opens the door to just the sort of rule by weight of numbers that persecution depends upon, localities (at least) should probably pursue consensus rather than majority approval.

(Sorry, no absolute solutions exist, no hard and fast realities. Each moment involves choice and chance. Control is not possible, only trust. And care. And forgiveness and understanding when mistakes are made.)

Progress

Would the process of plurocratic decision-making, especially if involving consensus, slow down the wheel of progress? Or grind it to a halt? Plurocracy might well take longer to decide what needs doing – but decisions will more accurately represent what people want. So, with sovereignty over themselves, perhaps people will make a less fast wheel, but for most it will seem a better wheel.

Certainly, with CAPE and a shorter working week, people will have ample spare time to properly deliberate over decisions, to seek and assess information, and to use their plurocratic abilities for change creatively and responsibly…