Losing The Game

Modern civilisation suffers from a critical systemic failure which cannot be fixed without a complete re-invention of the way we do business.

Orthodox economic theory – that old-time religion that worships god the profit, the job and the holy growth – claims that market competition causes the most efficient to succeed, while the lazy, incompetent or inferior are out-competed and fall by the wayside. This claim rests on many dubious assumptions and unlikely conditions, but, as I’ll explain, it’s invalidated by something more fundamental.

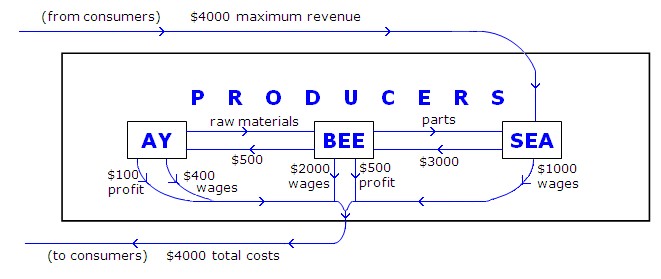

Most economics textbooks usually include, early on, a figure depicting the ‘circular flow of the economy’: businesses pay money to their workers, who use their earnings to buy the goods and services produced. The money that flows out from producers to consumers returns (unless some of it is saved). But this (too) simple overview hides the obvious: because prices include a profit margin (an amount over and above production costs), the amount of money distributed during production of goods – the payments made to do the producing and thus made available to consumers to spend – sums to less than the total prices of those goods.

As a result, not all businesses can profit: even if consumers spend all of the money paid to them by producers during production, they can buy only some of the goods available at their profit-inclusive prices. If some producers sell at a profit, others – regardless of their efficiency – will necessarily not recoup their expenditure: either they will be forced to sell at a loss or they will stockpile unsold goods they might be able to sell later… except that they face the same situation then as well. So, ultimately, some will profit, others might recoup their costs with nothing to spare, others will lose.

More detailed analysis confirms that not all businesses can sell all of their goods at profit-inclusive prices – the net profits for all businesses must sum to zero. The diagram below shows why. The three producers depicted can be treated as groups of different producers at the same ‘stage’ of production. For the period shown, ‘Ay’ and ‘Bee’ profit, but ‘Sea’, the producers of final consumable products, can at best recoup only their total costs – and only if workers spend all of the income they receive over the period, and Ay and Bee spend all of the profits they make over the period (their profits reducing to zero as a result). In this eventuality, some of Sea’s member businesses might manage to profit, but others must lose by the same amount.

On the other hand, if Ay and/or Bee retain any part of their profits (for investment or other non-consumption purposes), Sea’s members cannot even cover their costs – they make a net loss equal to the profits retained by Ay and/or Bee.

Of course, as textbooks eventually admit, the economic flow also has purchasing power added to it via exports, government spending, and credit. But even if the total of these exceed the total money leaving the flow via imports, taxes, and savings, still they do not prevent losses, they only transfer or delay them. Exports merely redistribute between national economies, shifting the burden without adding purchasing power globally. Government spending also only redistributes. Credit, a more complicated beast, initially adds to the economic flow, but repayment of the debt with interest – by which lenders profit – ultimately siphons more back than went out, depriving other competitors of their chance of profiting…

When credit is provided to producers, they must set prices high enough to cover their costs, make a profit, and repay their debt and its interest. Hence, producer credit can be treated as one of the ‘raw materials’ of Ay or ‘parts’ of Bee, necessary for Sea’s production. But then, producer credit does not change the dynamics: still, whether funded by credit or not, businesses who profit (whether by making goods or by lending money) deprive others of doing so.

Credit provided to consumers, however, works differently: it adds extra money, originating from lenders (‘outside’ the producers’ box), to the flow passing to consumers. Enough consumer credit could even cover every producer’s profit (in theory, although consumer expenditure would never be spread so evenly for this to actually occur), but even then, this could happen only initially: repaying consumer debt requires eventually foregoing some other purchase, which again means that eventually not every producer profits, or else the consumer defaults on the debt and the lender fails to profit.

Inevitable loss can at best be postponed, by injecting consumer credit into an economy more quickly than debt repayments siphon it back out, but because this leads to a rising level of debt, and of repayments, it cannot forever delay the day of reckoning – inevitably, debt fails to mount, losses occur, and the delaying tactic collapses. (Sound familiar?) A snake trying to swallow its tail must stop sooner or later, if only to throw up.

Don’t expect the eternal saviour of economic growth to help either. Growth just means more spending – yet the problem stems not from how much is spent, but how it is spent. Winners’ reinvested profits boost spending and growth, but losers have the opposite effect: their diminished expenditures, like those of any employees they consequently shed, reduce potential profits for others, retard growth and encourage recession. To achieve net growth, either debt or net aggregate profits are required, but the latter can only happen via mounting consumer debt. So, growth, like net aggregate profits, depends on continuously creating more debt than is repaid – on debt always mounting, and at just the right pace. When this inevitably fails to happen, growth falters, profits slump, losses mount, and economies collapse.

As all this follows directly and unavoidably because of the nature of profit, the dynamics of competitive market economies make them inherently unstable, prone to fall over sooner or later – and neither credit nor the obsessive-compulsive disorder of growth can prevent it.

For the same reasons, competition for profits also ensures that economic failure need not result from a lack of efficiency, discipline, skill, or any other advantage. The ideal that anyone with an idea and perseverance can prosper sounds enticing, but does not accord with economic reality, which more resembles a lottery. You can do everything right but someone else might do it with more luck and you will fail simply because not all can win.

Yet the economic rules that compel this are not god-given, self-evident, unalterable commandments. They have become entrenched due to historical accident, so ingrained from long use that alternatives evoke cognitive dissonance, but they remain arbitrary. Perhaps we have grown too used to the profit-mad economic flow and its deranged rules to consider changing, too habituated to recognise the addiction, but other more balanced and controlled rules – suited to modern times, needs and abilities – can be devised.

Pssst. New system for sale. It’s got the lot. A one-day working week. Afford anything deemed appropriate. No more financial hardship, unemployment, job insecurity, mortgages, rent, corporate tyranny. Save work without fear of losing income. Competition subservient to cooperation. Local stewardship, environmental care, international security, unfettered aid, truly sustainable development, political self-determination, change… You know you want it.