Plurocracy

Yes we can go for growth moving forward – it’s time.

The word democracy comes from two Greek words: demos, meaning people or population, and kratos, meaning power. So, democracy means people power – government by the people… at least in theory.

In practice, modern ‘democracy’ provides people not with the power to govern themselves, but with inadequate options between often misrepresented party devotees who, once elected, effectively run society (occasionally into the ground). Not choice but the relinquishing of choice, and the abdication of responsibility.

Power is not the sole province of ‘representatives’ however. It’s also shared by a few outside government: dominating contemporary ‘democracy’, mutually masturbating coalitions of political and economic forces constantly shift and realign as they overtly and covertly tussle for control. But although the elected and the elect may swap or share puppet and puppet-master roles as circumstances change and interests overlap or diverge, the concentration of so much power in so few hands prevents any possibility of true democracy.

Democracy also fails because of its one-size-fits-all approach. Many democracies elect political parties or squabbling coalitions with bare majority support. Neighbouring electorates often have diametrically opposed voting patterns. Yet governments claim mandates or consensus despite a clear and obvious plurality of views.

To avoid the failures of

‘democracy’, a bottom-up decentralised

participatory

system is needed, underpinned by small self-governing electorates

arranged into

progressively larger associations whose decisions require the majority

agreement

of constituent groups.

To avoid the failures of

‘democracy’, a bottom-up decentralised

participatory

system is needed, underpinned by small self-governing electorates

arranged into

progressively larger associations whose decisions require the majority

agreement

of constituent groups.

Call the arrangement plurocracy (since it correctly assumes a plurality of views), and base it on electorates called localities, each consisting of (say) 250 people (perhaps 200 old enough to vote).

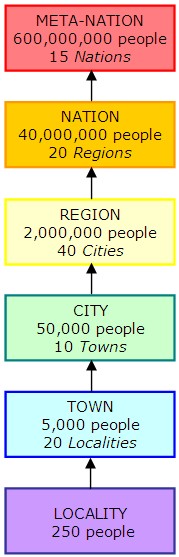

Groups of (say) twenty localities form electorates (of 5,000 people) called towns. Groups of towns, in turn, form larger electorates – groups of these, still larger electorates – and so on, with the biggest varying in size to suit population densities, ethnic and religious groupings, state boundaries, and other factors. To illustrate the idea (as in the diagram at right), ten towns might form a city (50,000 people), forty cities might form a region (2,000,000 people); twenty regions, a nation (40,000,000); fifteen nations, a meta-nation (600,000,000); and ten meta-nations, the world. Something like that.

At least at the locality level, voters make the decisions – for any and all issues with which they wish to be involved. Representatives ‘merely’ co-ordinate, providing or disseminating options and proposals to their electorates, and making sure they have all available and necessary information to make up their minds.

Decisions are made from the bottom up: for any electorate to plurocratically pass any proposal requires approval not only by a majority of the electorate’s voters but also by a majority of the electorate’s constituent electorates – each, in turn, approved also by a majority of their constituent electorates – all the way down to the locality level.

Plurocratic electorates at every level function semi-autonomously. Although each locality, for example, must heed the plurocratic decisions of its town, these apply only to issues affecting two or more localities (such as construction methods or building height restrictions). Each locality makes its own rulings for purely internal affairs (such as where to build a new house or shop, though recommendations for this might be made by its town or city).

Importantly, each electorate has the right to secede from its ‘parent’ electorate. If, for example, a locality found itself often voting against decisions plurocratically passed by its town, and felt enough dissent, it might choose to secede from its town, and join other more-like-minded localities (not necessarily with common borders) or else become independent.

Electorates might even determine their own definitions of ‘majority approval’ or vary it according to the issue, or seek consensus by modifying proposals until they satisfy all who previously dissented. Some might ‘weight’ votes in certain circumstances, so people most affected by decisions have the greatest say. Others might vote on a scale of (say) 0 to 100, with a pre-agreed average or median score required for any decision to be passed.

By whatever method they choose, each locality selects its representative from one of its own voters – most probably by voting for him or her, or by selecting different representatives for different issues, or by rostering representation among volunteers. Whatever the method chosen,representation is not faceless or unaccountable in an electorate of two hundred voters.

Similarly, each town selects their representative from their constituent localities’ representatives, or maybe the localities’ representatives make the choice, with town reps perhaps replaced or assisted at the locality level. Likewise for higher levels.

Much less complacent representation than occurs now can be further encouraged by storing the votes for all levels’ representatives online, each vote accessible to its owner to change any time he or she wishes. This saves the cost and tedium of periodic elections. And because power remains with the people, any change of representation merely means voters have changed their minds, not a potentially destabilising power shift.

The online voting system can also be used to register anyone’s opinion on any issue requiring a decision, seek and obtain ‘expert’ advice, bring any issue to the attention of those it affects, function as an electronic communal noticeboard, and allow any vote on any decision to be altered as voters plurocratically change their minds. True democracy from the comfort of your favourite armchair, with people self-governing – proposing, deciding, and implementing their own schemes whenever possible, advised by ‘experts’ when unavoidable, and coordinated by each level’s representatives directly answerable to their electors.

Something akin to plurocracy already operates – highly successfully – in Switzerland. It’s not as multi-layered, flexible or as feature-laden as this proposal, but even so it has probably helped avoid the religious feuds and ethnic cleansing that might have been expected in a nation comprised of various ancestries, about equal parts Protestants and Catholics, and with four main languages. Other important factors aside, it has undoubtedly encouraged a stable co-existence of diverse views, without which Switzerland would probably not have achieved its enduring peace and prosperity.

Plurocracy would probably take longer to decide what needs doing than does current democracy – but, as numerous recent political decisions have demonstrated, haste makes waste. In any case, this would be a small price to pay for decisions voters actually want – for returning power to the people.