Chapter 1

Symptoms & Disease

“Convictions cause convicts” – Gregory Hill[11]

Recipes for cooking our own goose abound: industrial-exhaust-led greenhouse steaming, deliberate or accidental nuclear barbecuing, chemical stewing, Peak-oil sautéing, population-bombed curing, ozone-depleted ultraviolet baking, and a host of other family favourites…

This chapter begins with an overview of the widespread ecological and social damage on which most doom ‘n’ gloom scenarios and predictions are based, before considering more optimistic views (section 1.1). To better comprehend how such opposing views can co-exist, various barriers to human understanding are discussed (1.2). Revisiting the arguments with those barriers in mind, a usually ignored or else blithely assumed central issue to both sides of the debate is highlighted: the indefinitely continued if not expanded functioning of competitive market economies. Accepting as very real the symptoms of ecological and social damage, they are assessed as incapable of being properly addressed without focussing on the underlying disease of market competition. (1.3). An overview of market competition is then given (1.4), including an explanation of why it compels ever more production, distribution, exchange, and consumption (which, in turn, require ever more work), how it inevitably fosters poverty and inequality, and how it generally causes rampant ecological degradation. Section 1.5 outlines a fundamental systemic flaw of market economies: how competition for profits sooner or later ensures loss for some players, and incessant instability. Loss cannot be avoided, not even by steadily increasing debt (because interest functions as another form of profit) or by economic growth (which only provides more of the same) – at best, loss can only be diverted by exports and government spending, or delayed by credit.

1.1 Half Empty Or Half Full?

“…the modern industrial system, with all its intellectual sophistication, consumes the very basis on which it has been erected…: fossil fuels, the tolerance margins of nature, and the human substance.”– E.F.Schumacher[12]We have been advised repeatedly for decades how we may be running out of arable soil, forests, food, water, fossil fuels, minerals, energy, living space… Our agricultural habits erode and cripple soil, and render rivers fit only for algae because of run-off from artificial fertilisers and other chemicals. Annually, we extract and process billions of tonnes of minerals, using methods which inject toxic metals, powders, liquids and gases into earth, water and air. Our cars and refrigerators belch greenhouse and ozone-depleting gases. Most forms of electricity generation, manufacturing, and mining fester with manifold pollutants. Chemical industry products infiltrate isolated waterholes and all levels of the food chain – toxic dioxins have been found, courtesy of humanity, even in polar bears. We pump raw or barely treated sewage into oceans, suffocating coastlines… litter the planet with tar, asphalt, cement, mountain ranges of throwaway plastic, old newspapers, discarded toys, construction rubble, and obsolesced machinery… make rain acidic, and now even risk an unstable climate. Other life wilts under our impact, whether cohabiting our cities or isolated in difficult and hostile terrain. Indeed, we plunder other life-forms not only for food, clothing, fuel and shelter to help us survive, but often more or less for the hell of it. Baby seals die so a rich few can pursue fur-lined ego gratification. Whales vanish to satisfy a few cultures’ parochial tastebuds; rhinos, so their horns can provide imaginary medicinal effects. Forest the size of small nations disappears every year,[13] partly to create throwaway chopsticks. So extensively do humans exploit other life that, if present trends continue, in about a hundred years, some estimate that as much as half the animal and plant species currently alive will have been wiped out.[14] Not all those that disappear will do so because of direct exploitation – many will simply get in our road.

While our activities undermine the earth’s capacity to sustain life, this of course has no advantage for us. Indeed, if we keep on doing what we are doing, we could put mother nature’s supermarket out of business, and starve ourselves to death. So, if we continue to act as though we own the planet, ownership must eventually have no value.

Our apparently rampant ecological problems are compounded by poverty and often widening inequality. While a minority in the developed world own and consume the vast majority of everything of value,[15] the least fortunate contend with hunger, homelessness, plague, or a zero or minimal income, resulting in tens of thousands of children dying each day[16] mostly from hunger and disease,and a billion or more landless.[17]

Yet inequality occurs not just between, but also within, nations: “Almost nowhere do the poorest fifth of households collect even 10 percent of national income, while the richest fifth commonly receive half.”[18] Even in many of the most developed nations, official poverty rates usually exceed one in eight (up to one in four) individuals.[19] For many poorer nations, the poor sometimes form a majority of the population.[20] Furthermore, the gap between rich and poor generally continues to widen, again both between and within nations.[21]

Ironically, poverty often prompts theft and other unlawful acts aimed at the relatively wealthy, adding to their worries: obesity, mortgage rates, health insurance premiums, job security and promotion or the constant potential threat of the dole. Meanwhile, rich and poor alike are beset by often escalating rates of violence, mental illness, stress, suicide, alcoholism, drug abuse, bigotry, intolerance, alienation, loneliness, civil disorder, and social disintegration.

Compounding our problems, poverty and ecological damage feed each other. Desperately poor people, especially the landless of the Third World, unable to look beyond day-to-day survival, often have no choice but to exploit their environment in unsustainable ways. Such behaviour can provide short-term success, but in the long run it perpetuates poverty by removing the land’s capacity to support life. And the effects spread beyond the poor. For instance, overgrazed land absorbs less water because of absent vegetation, and so erodes and floods more easily, passing the problems downstream to often richer landowners.

To many, these problems look if not insurmountable, then at least extreme, and warranting tough measures – or at least tough rhetoric.

Others, meanwhile, are not convinced. After all, doomsayers have often got it wrong…

For instance, early in the nineteenth century, Thomas Malthus expected population growth to soon outstrip food production, resulting in mass starvation – yet his predictions have been mostly thwarted (so far at least) because he did not anticipate many ingenious methods of food production developed subsequently.

More recently, in 1972, the famous Limits to Growth report[22] claimed that a continuation of trends then occurring would cause oil and copper to run out in a few decades, coal in two centuries, gold some years ago now, and almost all else within the next century or so – yet none of those forecasts so far have been borne out. The computer model used has been severely criticised for obscuring and excluding many factors and interrelationships, such as subtle economic feedbacks, unforeseen technological breakthroughs, even the resilience and fortitude of human nature. Quoting the computer maxim ‘garbage in, garbage out’, some suggested the model was based on inaccurate underestimates about existing resources, which consequently pre-determined gloomy but erroneous conclusions. For instance, one response stressed that: “Published estimates of [fossil fuel/mineral] reserves usually relate to proven quantities, recoverable under existing economic conditions. As more information becomes available the estimates for a particular reservoir are revised. In the past, a significant increase in reserves has occurred as initial estimates have been revised upwards. In addition to the geological uncertainties, conservatism in reporting initial discoveries has often been reinforced by commercial considerations.”[23]

So, maybe we shouldn’t panic after all. Maybe the doomsayers have it wrong. Or maybe they have exaggerated our glaring ecological and social problems: one recent and wide-ranging if hotly disputed assessment of mostly ecological indicators[24] claimed all sorts of relatively optimistic trends, even suggesting species extinction has been over-estimated by perhaps a hundred-fold. So maybe our problems aren’t as bad as we thought and they can be fixed with suitable efforts. Certainly, some have tremendous optimism.[25] For example, on the subject of hunger, according to Medard Gabel: “If the potential for multiple cropping in the tropics is tapped, world output of cereal crops could increase five or six times above its present level.”[26] According to Ted Trainer (though not an optimist), “one-third of the world’s grain production and half its fish production are fed to animals in rich countries… The entire problem of hunger in the world could be eliminated by the diversion of less than 3% of that grain.”[27] Food crisis? What food crisis? And what energy crisis? According to Gabel, “all the energy needs of the world could be met from non-depletable energy sources.”[28] The same or similar conclusions have been reached more recently by others.[29] We won’t run out of minerals either because, according to Buckminster Fuller, “metals once mined go into eternal recirculation… All that is needed is energy and knowhow to free them in pristine purity for further tasks. The United States has no tin mines, yet it has a tin reserve in aircraft and rocket production’s soft tools greater than the ore reserve in Bolivia’s great tin mines.”[30] Even the population explosion could be avoided if we developed quickly enough, because “populations tend to stabilize as industrialization increases. As a region’s life-support capabilities go up, the need for more people goes down.”[31]

Most who see the future optimistically rely on technology and ephemeralization – the doing of more with less, or raised productivity – to save the day. These ‘techno-optimists’ stand in stark contrast to the ‘neo-Malthusian’ doomsayers. Yet even some of those most convinced of looming eco-disaster claim it can be averted: for example, the Worldwatch Institute estimated in 1988 that reforesting, protecting topsoil, slowing population growth, moving to efficient renewable energy, and retiring Third World debt “could be achieved with [worldwide] annual expenditures approaching $46 billion by 1990 and increasing to $145 billion in 1994 and $150 billion in 2000”[32] – a tiny fraction of the world’s then annual $1 trillion defence budget. The 1992 Earth Summit reached similar conclusions. A 2009 update of the Worldwatch Institute approach estimated an annual expenditure for “social goals and earth restoration… of $187 billion, roughly one third of the current U.S. military budget or 13 percent of the global military budget.”[33]

But all this begs the question: how can doomsayers and techno-optimists examine the same situation and reach such widely divergent conclusions about the potential for ecological and social disaster, or its avoidance? Who should be believed – the pessimists or the optimists?

I suggest neither side should be believed. Both sides have valid concerns but both rely on extrapolating short-term trends – usually very short-term downwards trends of a few years in the case of some doomsayers, somewhat longer upward trends of decades for most optimists. This assumes a continuation of a single pattern, not a possible cycle or chaotic sequence from which a short-term trend has been isolated. Just because a crop yield fell for a few years, or rose for a longer period, does not mean either ‘trend’ will continue – too many complex factors interplay for simplistic trends to be assumed.

Consequently, I think both sides of the debate have only partial understandings. Both have some things right, and some wrong – and always will. The reasons for this abound…

1.2 Forests Of Trees

“…what are the criteria for the validity of any statement, of right and wrong, of true and false, of good and bad? There are none, independently of certain arbitrary points of reference, assumptions, or premises. And we can never be sure whether our arbitrary points of reference, assumptions, premises, or ends are actually valid.” – Michael Wertheimer[34]Human understanding rests on precarious foundations. Not only do our senses apprehend the world imperfectly, but our brains process the sensory data we receive in ways prone to misinterpretation and dependent on previous experience and habit.

The sensory information and stimuli received by the brain affect its growth and development. At birth, a young immature brain receives much novel sensory information which prompts trial-and-error reactions. Some ‘work’, others don’t. Hence, at first, babies try to touch fire. But when stimuli grow familiar through repetition, the brain ‘knows’ how to respond – with tried-and-proven semi-automatic reactions. Babies stop trying to touch fire. ‘Knowing’ appears to correspond to particular structural arrangements of the brain – specific circuits of, or associations between, neurons. Different lives, and thus different stimuli, lead to different brain structures. The most memorable or impressionable experiences imprint onto the brain in all but permanent, static, embedded structures. More flexible brain circuitry can be built onto imprints via conditioning (repetitious or otherwise significant experiences), and a third, very adjustable circuitry results from learning (each newly acquired fact or opinion probably corresponds to some small, newly adjusted brain circuit).

Thus, experience shapes the brain, but response to further experience is shaped by the brain. Indeed, experience can imprint brain structures and brew personal viewpoints so fixed that we sense only what supports our beliefs, ignoring the rest or excluding them as mistaken. Even when it grows obvious that our chosen reality no longer exists, if it ever did, our fixed brain circuitry can force us to refuse to admit it and continue to perceive only what we believe. Alas, it seems that the “human brain, which loves to read descriptions of itself as the universe’s most marvellous organ of perception is an even more marvellous organ of rejection.”[35]

The misperceptions of reality to which we stubbornly cling – our ‘tunnel-realities’ – may satisfy us for a time, but eventually they can seem absurd. People once believed in a flat earth, round which the sun revolved. Until the nineteenth century, nearly all scientists – supposedly the most adept conceptualisers and most rigorous perceivers and measurers of reality – refused to believe rocks could fall from the sky, against much evidence for meteorites.

But we don’t just deny perceptions that fit poorly into our tunnel-realities, we also fabricate others to suit. Biologists, peering through early microscopes, thought they saw miniature people inside spermatozoa. Physicists, for a while, saw N-rays, even when their detection equipment had not been turned on. Our past is strewn with various ‘experts’ who fervently believed what later proved false: that humans could never fly, or travel to the moon; that continents do not drift; that bacteria do not cause stomach ulcers; that stock markets would continue to rise. As a result of both intentional and unintentional indoctrination by such experts, as well as by parents of babies, teachers of students, peers of adolescents, social leaders of followers, media of users, and so on almost ad infinitum, the tunnel-reality we each permit ourselves to perceive is largely shaped for us, by others.

As a result, each society develops an overall ‘consensus tunnel-reality’, carved by social, political and economic conventions and structures, moral codes, religious beliefs, and various other habitual practices. Christian Capitalism. Atheistic Communism. Islamic Fundamentalism. Pagan Hedonism. Local Currentism.

Tunnel-realities, personal and consensus, are further reinforced by language. For instance, people who habitually use the word ‘businessmen’, rather than ‘businesspersons’, tend to feel surprise or shock upon meeting businesswomen. Similarly, repeated use of the word ‘housewife’ tends to cause us to disregard, or view as abnormal, househusbands. But sexist language only comprises the tip of the iceberg.

Alfred Korzybski explained in the 1920s that when words are identified with each other, in the manner of ‘A is B’, labels for one perception become associated with those for others, and emotional associations linked to one word transfer to the other. We perform these ‘identifications’ frequently – in common everyday exchange, heated arguments, simplistic slogans, political speeches, advertising – and each time, perceptions, descriptions and inferences merge into confused creeds…

He ‘is’ a bastard. She ‘is’ a slut. You ‘are’ wrong. The real problem ‘is’ unemployment (or inflation or global warming or immigration or whatever’s fashionable). The current USA president ‘is’ an imperialist dog. The nation currently number one on our country’s hate list ‘is’ an evil empire (or a pack of butchers or something newer, nastier and catchier than what was last said of them or their predecessors). With this drink, the opposite sex ‘is’ easy meat.

All identifications, even those based on seemingly indisputable observations such as ‘grass is green’, mislead to some extent (in a drought, grass ‘is’ yellow, brown, even white, but rarely green). According to Korzybski, even ‘John is a carpenter’ comprises an identification – not normally emotive, but still misleading because “the characteristics of a class [carpenter] are not the ‘same’ as nor identical with the characteristics of the individual [John].”[36] Although John might now work as a carpenter, come the next recession, he might not; to then say that John ‘is’ an unemployment statistic, or a dole-bludger, would likewise oversimplify and misrepresent him. Korzybski argued that we can say ‘John is not a cat’ because this states difference not sameness. But “whatever one might say something ‘is’, it is not”,[37] because the ‘something’ – the reality – changes over time, and remains much more than any sounds we use to very roughly categorise our brief subjective imperfect perceptions of it. The map is not the territory.[38]

According to Korzybski, identification works against understanding so effectively as to produce “results [which] are semantically and structurally far-reaching and are found to underlie modern mythologies, militarism, the prevailing economic and social systems, the control by fear (be it ‘hell’ or machine guns), illusory gold standards, hunger etc.”[39]

So, casual identification augments our brain-structured tunnel-realities, personal and consensus, to make us creatures of habit, devoted to fabricating and defending our personal ‘truth’ and denying that of others, committed to our ideologies and dominant paradigms. Or as an old saying puts it, you can’t teach old dogs new tricks – at least not without a lot of work.

No wonder we suffer from what has been called ‘confirmation bias’, by which we “seek out and believe evidence that fits with our preconceived ideas while ignoring or dismissing the rest.”[40] We confirm what we think we already know, and discount what we don’t. Thus we resolve – in an illusory way – a natural urge for certainty in an uncertain world. Even supposedly objective scientists are not immune. In the words of two physicists: “Paradigms, especially after they have been established for some time, hold the consensual mind in a ‘rut’ requiring a revolution to escape from. Such excessive rigidity amounts to a kind of unconscious collusion, in which scientists unconsciously ‘play false together’ in order to ‘defend’ the currently accepted bases of scientific research against perceptions of their inadequacy.”[41]

In social sciences, the behaviour studied has less orderliness and predictability than that dealt with in ‘harder’ sciences. But social scientists can be thwarted less by the inherent difficulties of their field than by their own tunnel-realities. One social scientist, an economist, wrote: “Hidden valuations and normative judgements which parade as analytical… statements, the tendency to put one’s conclusions into definitions and assumptions, reasoning by analogy and by past experience, wishful thinking and self-deception, deliberate suppression and manipulation of information by interested groups, preconceptions including distorted time-perspectives and, last but not least, elements in the personality structure of the investigator – these are some of the obstacles which tend to defeat social inquiry by subverting the required critical and dispassionate attitude of the social scientist.”[42]

Another economist, a ‘Nobel’ Prize winner, explained it in different terms: “Ideology provides a lens through which one sees the world, a set of beliefs that are held so firmly that one hardly needs empirical confirmation. Evidence that contradicts those beliefs is summarily dismissed. For the believers in free and unfettered markets, capital market liberalization was obviously desirable; one didn’t need evidence that it promoted growth. Evidence that it caused instability would be dismissed as merely one of the adjustment costs, part of the pain that had to be accepted in the transition to a market economy.”[43]

Tunnel-reality, paradigm, ideology, preconception, confirmation bias, even cognitive dissonance – call it what you will, but it poses an enormous barrier to understanding anything other than what we already believe, which may or may not be based on repetition of errors or outright lies. Ultimately, it all depends on who you believe, who you trust.

1.3 Second Opinions

“…were the current orthodoxies reliable and the policies they advocate applicable, we wouldn't be in the trouble we are in. We have seen the present and it doesn't work.”– John K.Galbraith[44]So, because of tunnel-reality dominance, neither the neo-Malthusian doomsayers and eco-worriers nor the techno-optimists should be believed as having the full truth. We may desire black and white, but reality has far more shades of grey.

Given the complexity of ecological systems, we can probably never have complete certainty about the extent to which they have been damaged, or why, or their capacity to recover. Even so, because damage can be clearly seen all about us, it can’t be dismissed as negligible.

Looking as dispassionately as I can at the evidence and conflicting opinions about it, I’m forced to conclude that humanity is having a marked deleterious effect on its environment, one which could reach perilous extremes sooner or later, and almost certainly has in some regions of the world already. Malthus and other doomsayers may have got it wrong in the past, but maybe their predictions have not been thwarted, instead merely delayed.

Undoubtedly, optimists would counter that humans have capacities to overcome all threats, that practices we have adopted and which have previously delayed the worst Malthusian fears can be enhanced, augmented and continued indefinitely. Perhaps best summing up this view, Buckminster Fuller wrote: “There is no energy crisis. There is a crisis of imagination.”[45] But the crisis works in both directions – too little imagination for some, too much for others…

The what-looming-disaster school don’t have their heads stuck in the sand, but maybe they have them too firmly wedged in economics textbooks and operatic science-fiction novels. To some techno-optimists, like Herman Kahn,[46] Gerald O’Neill[47] and Daniel Bell,[48] not only can humanity avoid disaster but it can grow indefinitely. Automation, information technology, biotechnology (genetic engineering), nuclear fusion and/or some other hi-tech power, and the final frontier of space, will all allow the limitations of a finite planet to be transcended. No limits to growth in an infinite universe. New industries will take us on and on, expanding forever with no strain too much for our economic system to handle. All problems will be sorted out on the way by science and the purported common-sense of the market. Indeed, according to proponents of this view, most problems that look like looming disasters “are more the growing pains of success (often accentuated by ill-timed bursts of mismanagement as well as the needlessly dire prophecies of doomsayers) than the inevitable precursors of doom.”[49]

At the very base of their beliefs, most techno-optimists rely on the market to move us forward and beyond, trusting in its purported wisdom to cure all problems. But then many doomsayers also ultimately assume much the same, albeit usually with some additional government regulation of markets. For instance, the Worldwatch Institute’s aforementioned estimate of the money needed to avert disaster assumes the continuance of market economies.

Of course, who could fail to notice the achievements of market economies? Even allegedly communist China has hopped onto the bandwagon. No wonder. Through market competition, successful nations – their most profitable competitors at least – have raised their standards of living sky-high, and faster than a speeding bullet, in the process doing away with many of the hardships that have defined human existence since we dwelt in caves.

And yet, despite the avowed superiority of market economies, despite them being constantly touted as successful beyond peer, and admired with not merely religious but often fanatical devotion, occasionally they are acknowledged as also sometimes failing abysmally – even by their most ardent defenders. When the 2006 Stern Report called the threat of climate change “the greatest market failure the world has seen”, the then Australian Federal Treasurer would not agree, pointing out that “we have seen market failures that have led to wars and famine and global poverty”.[50] With market enthusiasts like this, who needs critics?

At least one noted techno-optimist did not think the market could be relied upon to solve our problems. Buckminster Fuller long claimed that the ecological and social problems we face stem not so much from ephemeralized technology, as many neo-Malthusians suggest, but from its subservience to market competition, from the continued insistence that we compete rather than co-operate for wealth – a primary issue that the standard techno-optimist stance, and the typical neo-Malthusian, ignores. Convinced that if nations stopped concentrating on weaponry for the defence of competitively won advantages, and instead poured the same energies into “livingry”, Fuller maintained that within a decade or so, abundance could be shared worldwide – whereas continued competition would guarantee oblivion for all. Thus, to Fuller, the market offered not the means of eternal beneficial growth favoured by most techno-optimists, nor even a hope for averting neo-Malthusian disaster if suitably regulated, but rather ultimate doom.

I agree with Fuller on this crucial point. As the next section will outline, and the rest of part one of this book will detail, the very rules of market competition inevitablycause and perpetuate widespread, often increasing, poverty and inequality, and all but inevitably cause ecological degradation. Hence, as long as most doomsayers and techno-optimists alike assume market competition, they deal with symptoms not the disease. And as any half-decent medic knows, a cure depends on treating the disease not the symptoms.

Warning: cognitive dissonance ahead.

1.4 The Economy & Other Disorders

“…modern capitalism is absolutely irreligious, without internal union, without much public spirit, often, though not always, a mere congeries of possessors and pursuers. Such a system has to be immensely, not merely moderately, successful to survive.” – John Maynard Keynes[51]Two economic systems have dominated the last century or so: capitalism and socialism. The latter has been largely abandoned as a failure, while the former has been adopted by more and more nations – apparently, a big winner (or is that ‘wiener’?).

Capitalism, also known as free enterprise and private enterprise, has been defined as “an economic system in which the means of production are privately owned and operated for profit.”[52] Although accurate, this leaves out something crucial: owners of the means of production (a minority of the population) compete with each other to make profits, just as those they pay to work for them (the majority) compete for jobs and wages. Fundamentally, capitalism revolves around competition – more generically, ‘market competition’.

To profit from market competition, a business must gain more money from sales than it spends during production of its goods or provision of its services. More pedantically, when costs include payments for labour of business owners roughly equal to those that would be paid to anyone else for similar labour, profit goes by the official name of economic profit – “the difference between revenue and economic cost”.[53] Although owners are often rewarded more lavishly than this, the discussion henceforth treats ‘profit’ and ‘economic profit’ identically.

Businesses who use more efficient methods, or cheaper resources such as labour, can sell for lower prices than their competitors, and because lower prices generally attract more consumers, these businesses tend to make more profits. But, unsurprisingly, not all can win at market competition. Although, theoretically, every individual can own something and thereby manage and control it for his/her own reward, market competition always results in some (‘winners’) owning and controlling a lot, and others (‘losers’), next to nothing. In the words of one of the most famous and eloquent twentieth century economists, John Maynard Keynes, capitalism constitutes “a method of bringing the most successful profit-makers to the top by a ruthless struggle for survival, which selects the most efficient by the bankruptcy of the less efficient. It does not count the cost of the struggle, but looks only to the benefits of the final result which are assumed to be permanent. The object of life being to crop the leaves off the branches to the greatest possible height, the likeliest way of achieving this end is to leave the giraffes with the longest necks to starve out those whose necks are shorter.”[54] In other words, losers and therefore poverty and inequality follow inevitably from market competition.

Textbooks claim that no-one can keep making profits for long, that a firm’s profit now balances with a loss later, and that in “the long run, economic profit for any firm in a competitive industry is zero… due to downward pressure on product price and upward pressure on factor prices”.[55] But in fact, profits for some industries do not average zero, they instead remain positive for substantial periods of time,[56] because, in this game, winning increases the chances of continuing to win, and likewise losing fosters more losing – hence, wealth tends to concentrate, and inequality generally increases.[57]

Market competition’s inherent tendency to widen the gap between rich and poor can be offset by altruism or government intervention, but neither follow naturally from the economic game rules. Nevertheless, recent research suggests that it doesn’t pay to have too much inequality, even for the rich: “even those at the top are better off if their society is more equal, regardless of their relative level of actual wealth. Studies… consistently show that greater equality improves wellbeing even for those in the top 25 percent.”[58] Factors of well-being consistent with this finding include “life expectancy, obesity, imprisonment rates, teenage pregnancy, mental health, levels of trust in the community, education performance, status of women, and [more]… most of the indicators being three to ten times worse in more unequal societies. This applied even when none of the subjects in the group being researched were anywhere near what could be considered poor. So, for example, among U.K. civil servants in Whitehall, all well paid by global standards, the bottom of the group had a death rate three times as high as the top of the group, of which only a third could be explained by other causes like obesity and smoking (and some of those were perhaps driven by inequality anyway).”[59]

Given capitalism’s inherent tendency towards widening inequality, it naturally didn’t take long for it to inspire the development of ‘socialism’, first as theory in the mid nineteenth century, and then in the next century as practice. Socialism advocates not private but social ownership and control of the means of production, distribution and exchange. Yet ‘social ownership and control’ has considerable ambiguity. In every nation so far to have attempted socialism, ownership and control have largely or entirely resided with the state – the various levels of government, and the military, judicial, police, administrative and other groups in their employ. Alas, centralised control of economic activity by distant bureaucratic overlords has mostly proved destructive to both the environment and to the general population. Saved from competing for profits, people suffered instead from a lack of incentive and involvement, which dissuaded innovation and ultimately led, in most cases, to the jettisoning of socialism in favour of capitalism. China, Cuba, Venezuela and some other South American nations still claim socialism, but all have a degree of private ownership of the means of production and market competition for profits, which leaves them socialist in little more than name only.[60] More accurately, they have adopted merely a more government-regulated form of capitalism rather than the pure unregulated ‘laissez-faire’ version (which, strictly speaking, no nation practices).

So, capitalism dominates today. And yet, it is compelled by its own game rules to dominate even further – to grow, relentlessly, perpetually. If it can…

A growing economy, by definition, spends more money. For all the talk about, and priority given to, economic growth, it consists of nothing more than increasing expenditure (adjusted for inflation). Competition for profits compels it, because businesses that gain profits are obliged to invest much or all of them in new ventures intended to increase their profits, thus boosting production and spending, which equates to economic growth. If businesses don’t reinvest, they risk shrinking profits and ultimate loss, because either their markets will become ‘saturated’ with too many consumers already having purchased their goods, or newer products will supersede theirs, or they will be out-competed eventually by other businesses that do grow.[61]

So, the compulsion to grow is built into the game rules of market competition.

But not only businesses have compelling reasons to want economies to grow, so do wage earners. If an economy does not grow, if instead its spending reduces, it has less need for production and work – and because less work almost invariably means less income, this causes obvious problems, not only for those whose income reduces, but also for the producers of the goods that might otherwise have sold if income had not reduced. Failure to grow thus encourages more of the same. Or, as Tim Jackson succinctly put it: “Growth is necessary within this system just to prevent collapse.”[62]

The same undesired effects follow even if an economy’s spending somehow stays static, neither growing nor contracting: in this rare situation, efforts to maximise profits still unleash productivity improvements that reduce the need for workers, meaning less income and spending, and a conversion of no growth to reduced growth, with all its associated problems. Hence, a no-growth or ‘steady-state’ economy, though increasingly advocated, cannot be maintained if profit maximisation is pursued.[63]

Clearly, profit-driven market economies are compelled to grow. No surprise then that growth is widely promoted as a cure-all. We are constantly told how growth, a simple easily digestible measure of national success in a complex hard-to-fathom world, bakes a bigger economic cake, so providing more to eat for the same share. Yet market competition’s steady churning of winners and losers actually causes the various sizes of slices of the economic cake to constantly change, usually resulting in widening gaps between rich and poor, within nations and between them. So, rather than growth causing everyone to eat more because of a bigger economic cake, instead it tends to result in winners eating more but losers less.

Just as importantly, a bigger cake is not necessarily tastier or more nutritious: widespread growth since World War 2 has seen unpaid social and ecological costs poison many slices of the economic cake. No wonder: because growth concerns only quantity not quality, perhaps forty percent of all money spent cleans up the mess made by the rest.[64]

Yet it is not growth per se that causes ecological degradation – rather, it follows, like poverty and inequality, from market competition itself. But whereas poverty and inequality follow inevitably in principle from market competition, ecological degradation follows from it ‘merely’ generally in practice. As the next chapter details, profits can be maximised by minimising or avoiding costs, which often involves using production methods that erode, deplete, pollute and/or in some other manner degrade the environment. Unless governments decide to try to regulate ecologically damaging practices, most businesses continue to use them because doing so maximises their profits. Growth ‘merely’ compounds the extent of the damage, by involving more expenditure and more production.

The environment, clearly, is not the economy’s first priority – nor that of governments. Profits and growth take precedence. So, for example, various corporations keep pumping out greenhouse gases as they amass profits and help sustain growth. They are exonerated by widespread and dominant faith that ‘the market knows best’, that some of the profits gained will fund investment to eventually discover new ways to operate without the alleged ecological costs (such as by developing renewable alternatives). Some governments might try to hasten market progress by imposing carbon taxes and emission trading schemes[65] which increase costs and add layers of complexity but do not directly change the methods in use nor the message: keep operating in ways seen as dangerous and damaging until you can eventually afford to figure out how to operate safely. Keep doing things wrong until you can afford to do them right. Profit and growth first, all else second. If the same approach was taken towards thieves, they’d be allowed to keep stealing until they could afford to go straight.

So, with growth and profits the priorities, competitive market economies require ever more activity, ever more building, extracting, transporting, generating, producing, all to spend ever more money, in order to buy more, to use more, to make more, to spend more to buy more to use more to make more to spend more… ever more… whatever the associated costs. Not mere compulsion, but obsessive-compulsion.

And yet, however much we single-mindedly pursue our arrested adolescent idée fixe about the size of our spending, and however much social and ecological damage we cause in the process, the goal of ever more growth remains elusively out of reach, interrupted irregularly by recession and depression. These occur when an economy spends less, even the tiniest percentage less, for just six months or more – which happens frequently: most countries experience at least one recession every decade (see section 5.2).

The inevitability of recessions indicates the obvious: despite market economies being compelled to grow, perpetual growth is simply not possible. This can be seen most glaringly by considering natural resources: if we keep increasing our extraction of the top ten minerals by the modest three percent growth rate economies usually aspire to as a bare minimum, then in a thousand years we’d need to be digging up an amount weighing more than the entire earth.[66] Talk about digging your own grave.

Some optimists suggest we can grow eternally, without ever more resource extraction, by recycling, ephemeralization, and/or expansion of service and information industries. In other words, some constant or declining amount of energy and materials could sustain ever more information processing and service provision. Although possible in the short-term (if resource use can reverse its general tendency to increase[67]), this futile hope cannot succeed in the long run, particularly if the global population stabilises, as trends suggest it will by about mid-century. Even if somehow involving a stable or decreasing level of resource use, for a roughly constant number of people to exchange ever more money for ever more provision of services and information, they would have to either spend more and more time in that provision and exchange, or else find ever more productive ways to provide more, or a combination of both. Yet surely, eventually, a physical limit must be reached as to how often and efficiently we can all research our family trees or have our hair cut or palms read or nails manicured or eat out – even the modern economy cannot give us more than 24 hours in each day to consume.

So, at least as long as we remain restricted to the one finite planet, it seems certain that market economies can only grow so much before they consume their natural resources and/or reach their limits, and then contract.[68] Although the methodology of the original Limits To Growth report can be criticised, and the forecasts from its more pessimistic scenarios have not eventuated – although other neo-Malthusian arguments may not have proved correct in detail, their forecast calamities overdue or overstated – still their fundamental argument holds true: exponential trends like economic growth cannot be continued indefinitely in a finite system. Yet our economic game rules compel us to try to always grow. Catch-22.

Ironically, obsessive-compulsive, socially and ecologically destructive, unsustainable, competitive market economies also suffer from a sort of split personality: their dynamics compel growth, but also work against growth. Businesses try to maximise profits not just by reinvestment and expansion, but also by reducing costs, either via automation, increased productivity, or out-sourcing to cheaper labour in other nations. However it is achieved, reducing costs usually causes jobs to be lost, leaving consumers with less money to spend, and hence, businesses with fewer potential buyers of their goods.[69] Thus, trying to maximise profits contradictorily risks reducing profits (and growth), unless replacement jobs to produce new goods and services are perpetually created. So, competitive market economies must aim not just for more spending and more profits, but also for more work. Ever more. In the name of the profit and the job and the holy growth.

Not just businesses and workers, but also banks and other financial institutions have a vested interest in the creation of jobs and maintenance of growth: for loans to producers to be repaid, they must finance enterprises that eventually make sufficient profits to cover the costs of servicing the loans, which means more spending. Similarly, if consumers spend less, not only do they have less need to borrow money, but also fewer sales happen, and therefore profits reduce, leaving businesses with less money to repay debts. So, like any profit-seeking business, lenders want growth.

But lending money also compounds the split personality of market economies: repaying business debt depends on growth – more spending – but consumers can only repay their debt by foregoing spending, by saving. Of course, ‘too much’ saving means no need to borrow money in the first place but also too little spending for an economy to grow – anathema to lenders and business. On the other hand, ‘too little’ saving can mean profligate spending leading to inflation and debt bubbles.

Compounding the issues further, while lenders depend on growth to allow debt to be repaid, growth also depends on debt in order to happen at all: to spend more requires having more available to be bought, which requires higher productivity and/or more production facilities – the former usually and the latter always require investment via profits and/or debt, but because profits ultimately cannot be made in aggregate without debt, this makes growth entirely dependent on debt. To understand why net aggregate profits cannot be made without debt, some little known facts need to be detailed…

1.5 Profits Of Doom

“…profit earned by one capitalist must be at the expense of someone else—be it worker, other capitalist, or banker. ”– Gunnar Tomasson & Dirk J.Bezemer[70]As explained, economic competition has two possible broad outcomes. Either we spend more money, so we can make more profits and repay more loans and create more work to replace jobs lost because of the way previous profits were increased, in order to earn more money and make more profits and create more work and repay more loans made to allow us to spend more money, so we can spend more money and make more profits and repay more loans and create more work, so we can spend more money… spend more money… more… more… more, you can do it for me baby, keep going, keep going, aaah, aaaaaahhhhh… uhh… eh?! Or, we fail to grow: spend less, shed jobs, make fewer profits, repay fewer loans, suffer bankruptcies, financial collapse, recession, and the economy disappearing up its assets.

Yet this sad dilemma is made even more difficult by the nature of profit.

Because prices include a profit margin (an amount over and above production costs), the amount of money distributed during production of goods – the payments made to do the producing and thus made available to consumers for spending – sums to less than the total prices of those goods. As a result, not all businesses can profit: even if consumers spend all of the money paid to them by producers during production, they can buy only some of the goods available at their profit-inclusive prices. If some producers sell at a profit, others will necessarily not recoup their expenditure: either they will be forced to sell at a loss or they will stockpile unsold goods they might be able to sell later… except they face the same situation then as well. So, ultimately, some will profit, others might recoup their costs with nothing to spare, others will lose.[71]

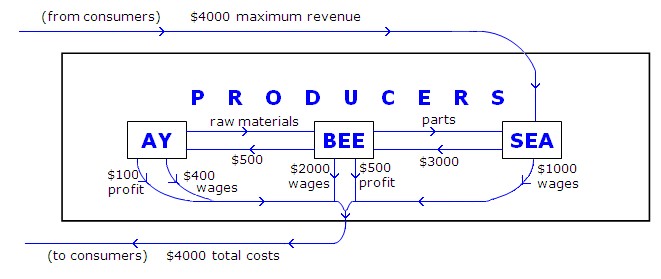

More detailed analysis confirms that not all businesses can sell all of their goods at profit-inclusive prices – the net profits for all businesses must sum to zero. Figure 1 below depicts a hypothetical example which shows why. The three producers depicted can be treated as groups of different producers at the same ‘stage’ of production.

Figure 1: Zero Net Profits

For the period shown, ‘Ay’ and ‘Bee’ profit, but ‘Sea’, the producers of final consumable products, can at best recoup only their total costs – and only if workers spend all of the income they receive over the period, and Ay and Bee spend all of the profits they make over the period (their profits reducing to zero as a result). In this eventuality, some of Sea’s member businesses might manage to profit, but others must lose by the same amount.

On the other hand, if Ay and/or Bee retain any part of their profits (for investment or other non-consumption purposes), Sea’s members cannot even cover their costs – they make a net loss equal to the profits retained by Ay and/or Bee.[72]

For both eventualities, any extra spending resulting from investment of retained profits is balanced by the reduced spending caused by the necessarily accompanying losses – meaning no growth.

Of course, the ‘flow’ of monetary exchange in a national economy also has purchasing power added to it via exports, government spending, and credit. But even if the total of these exceed the total money leaving the flow via imports, taxes, and savings, still they do not prevent losses, they only transfer or delay them, and so, for a while, effectively hide the fact. Competitive market economies can shoot up on as many liquidity injections as they like, but, still, purchasing power cannot buy all goods while their prices include profits…

Exports merely redistribute between national economies, shifting the burden without adding purchasing power globally.[73] Government spending also only redistributes – within rather than between nations. Credit, a more complicated beast, initially adds to the economic flow, but repayment of the debt with interest – by which lenders profit – ultimately siphons more back than went out, which deprives other competitors of their chance of profiting…

When credit is provided to producers, they must set prices high enough to cover their costs, make a profit, and repay their debt and its interest. Hence, producer credit can be treated as one of the ‘raw materials’ of Ay or ‘parts’ of Bee, necessary for Sea’s production, and profit-seeking lenders can be treated as ‘just’ another type of producer. But then, producer credit does not change the dynamics of Figure 1: still, whether funded by credit or not, businesses who profit (whether by making goods or by lending money) deprive others of doing so.[74]

Credit provided to consumers, however, works differently: in Figure 1, it would add extra money, originating from lenders ‘outside’ the producers’ box, to the flow passing to consumers. If spent on the products of Sea, consumer credit could allow Sea to profit – initially. But because borrowers must eventually repay their debt with interest,an amount over and above that previously added by the loan to the economic flow ultimately must be subtracted from the flow. This again denies others of their chance of profiting, as an example best demonstrates…

Assume in Figure 1 that Ay and Bee spend rather than retain their initial profits (meaning they end up with zero profits), and that $500 credit is leant to other consumers, making a total of $4,500 available to buy Sea’s products – this would allow Sea to make $500 profit. But for consumers to repay the $500 loan, plus interest of say $50, they must subsequently save a total of $550 – this cannot be spent on consumption, it requires foregoing some other purchase(s). If, for simplicity of explanation, the savings are accrued in the next period, then Sea can at most receive $3,450 for its products by the end of that period, making a loss of $550 for the period (or delaying it by retaining unsold goods), and a total loss over both periods of $50 – the amount by which the lender profits. In other words, lenders’ profits, if realised, must eventually ensure a corresponding loss for others.[75] Alternately, if consumers default on any part of their loans, lenders suffer losses equal to the total profits made by Ay, Bee and/or Sea over the periods in question. Either way, over time, for producers and lenders together, profit and loss must still balance.[76]

Conceivably, consumer credit could be injected into an economy more quickly than debt repayments siphon it back out. As long as this was kept up, as long as consumer debt mounted, producers could keep making net aggregate profits.[77] And debt does indeed increase in modern economies, at least as long as they are growing.[78] No wonder: it’s all intertwined, profits, growth, debt, each feeding on and dependent on the other. The end of the last section explained how lenders depend on growth to allow debt to be repaid, and how growth requires profits and/or debt, but because net aggregate profits cannot occur unless consumer debt mounts, growth depends ultimately just on debt.

Unfortunately, not only does saddling consumers with mounting debt in order to enable net aggregate profits seem a dubious tactic for achieving economic growth, just as importantly, it does not work for long. Alas, debt does not always mount, just as economies do not always grow. When recessions strike, as they inevitably do, debt usually dips or at least stops growing, and the postponed losses occur. Indeed, sometimes, as for the Great Recession, debt mounts too quickly to be sustained and its sudden dip causes recession via a calamitous surge of losses. Obviously, consumers unable to repay their debts suffer – adding to problems of poverty and inequality – but so do producers who depend on them to consume. So even a mounting level of debt has an actual outcome of merely delaying not preventing inevitable loss, of putting off the day of reckoning via a precarious and ever-mounting stack of cards prone to eventual collapse when one decent economic sneeze causes the lenders themselves to lose.

Now if economies could always grow, the delaying tactic of mounting consumer debt might be made to work: perpetual growth, the spending of ever more money, would not obviate the dynamics that ensure loss – still some would lose – but it would postpone many losses by allowing consumer debt to ever mount, which, in turn, would allow the economy to ever grow (and vice versa). Even so, like the mounting debt itself, an economy would have to always grow at just the right pace. Too much growth yields inflation (see section 4.5), too little and jobs are not created quickly enough to compensate for those lost to rising productivity or cheaper competitors – with either outcome, debt is prevented from mounting at the required rate.

In practice, history attests that economies rarely grow at just the right pace, and never for long – so, clearly, an optimum level of growth cannot be maintained indefinitely.[79] No wonder: as the last section explained, competitive market economies constantly try to run in two different directions at once. Repaying business debt depends on consumers spending more, but consumer debt can only be repaid by saving – spending less. Likewise, trying to maximise profits by cutting costs means shedding jobs and distributing less money to the very consumers whose spending enables those profits, so it contradictorily risks reducing profits and growth.

These opposing tendencies, like all of the problems and difficulties associated with growth, ultimately stem from the fundamental driving force of market economies: competition. To make this clearer, a brief summary of the foregoing details about profit and debt follows…

Competing capitalists try to profit, but only some can succeed: in the absence of mounting consumer debt, profits balance losses. Winners can reinvest their profits, thus boosting spending and growth, but losers have the opposite effect: their diminished expenditures, like those of any employees they consequently shed, reduce potential profits for others, retard growth and encourage recession – which makes life more difficult even for winners. To achieve net growth, either debt or net aggregate profits are required, but the latter can only happen via mounting consumer debt. So, growth and net aggregate profits depend on continuously creating more debt than is repaid – on debt always mounting, and at just the right pace. When this does not happen, as inevitably occurs because of the aforementioned contradictory impulses at work and the sheer impossibility of indefinitely maintaining the necessary rate of increase while simultaneously repaying ever more, growth falters, profits slump, losses mount, and the processes collapse.

Hence, directly and unavoidably because of the nature of profit and interest, the dynamics of competitive market economies make them inherently unstable, prone to fall over sooner or later. Those dynamics and their consequences cannot be thwarted by either mounting debt or the obsessive-compulsive disorder of growth – only revising the economic game rules offers any hope.

In essence, capitalism’s fundamental processes force it to operate as a sort of grand Ponzi scheme (a fraudulent investment fund which pays dividends to members from their own invested funds). Ponzi schemes ‘work’ as long as a sufficient number of new investors continue to be found, but when this fails to happen, or when enough investors for whatever reason decide to withdraw their money, the process falls apart and losses ensue. With capitalism, just as for a Ponzi scheme, many or most players aim or expect to get more money back than they put in – not just businesses via profit and banks via interest, but also investors via their invested money. Via credit, the semblance of profit is gained, but repayment of debt with interest must ultimately spoil the illusion. Just as Ponzi schemes eventually unravel, so too must capitalist expectations be disappointed: to have more returned than is contributed cannot be maintained, indeed, ultimately makes no sense. Loss is guaranteed, sooner or later.

The inevitability of loss should not surprise: whoever heard of a competition in which everyone wins? Competition means someone has to lose.

Yet most economists pay little attention to loss, or even to profit. Indeed, although the significant question of how producers can possibly obtain net profits in aggregate – now known as ‘the paradox of profits’ or ‘the profit puzzle’ – was raised in the nineteenth century, and prompted many attempts to resolve it, it has been largely ignored since the Great Depression.[80] Karl Marx believed his concept of ‘surplus value’ allows net aggregate profits to be gained, and so solves the puzzle, whereas Keynes reached the same conclusion via what he called ‘user cost’. Both solutions have been criticised as inadequate.[81]

More recently, the ‘Circuitist’ school of economics concluded that producer profits in aggregate must sum to zero, though they seem split as to whether they have reached a valid conclusion or have analysed erroneously.[82] However, recent work by Gunnar Tomasson and Dirk J.Bezemer reached the same conclusion as my own: that only mounting consumer debt can allow net aggregate profits to be realised.[83]

Yet because debt cannot always mount at just the right pace, the goal of profit, however it might motivate innovation, productivity and activity, guarantees loss for someone, somewhere, sometime or another, and thus ensures economic instability. Remember, too, as the last section explained, that market competition for profits also guarantees poverty and inequality, and all but assures ecological degradation.

One might think all of this would make for not just an unstable system but a very inefficient one as well, yet economists have long argued the opposite: orthodox economics claims that market economies allocate their resources so efficiently that they enjoy optimal outcomes. The next chapter examines this dubious claim, and shows that in order for it to hold, prices must function as accurate ‘market signals’ for resource allocation, an assumption invalidated by many considerations, especially the extent to which businesses leave out many relevant costs and subsidies when setting prices. The reality of not optimal but very imperfect prices instead results in meaningless profits: as the next chapter details, profits are often (if not generally) exceeded not only by the costs of social and ecological damage inflicted by businesses, but also by the government subsidies they receive. If properly and fully accounted for, perhaps no business would ever truly profit.

In addition to the inherent inaccuracy and sometimes just plain meaninglessness of prices and profits detailed in the next chapter, other problems inherent to both the theory and practice of competitive market economies will be discussed in the rest of part one. These further details reinforce the conclusion forced by what has been explained so far: that competitive market economies have fundamental dynamics that compel inevitably thwarted attempts at ever more producing, distributing, exchanging, consuming and debt, with individual profit as the first priority, perpetual invention of work as a necessary accompaniment, instability, inequality and poverty as inevitable consequences, and ecological damage as an all but inevitable consequence – all symptoms that cannot be cured without tackling the disease, without moving beyond market competition for profits.

Part 1 Part 1 |

Chapter 2 |