Chapter 2

Costs & Prices

“No other civilization has permitted the calculus of selfishness so to dominate its lifeways, nor has any other civilization allowed this narrowest of all motivations to be elevated to the status of a near categorical imperative.”– Robert L.Heilbroner[84]Market economies play the game of competition, but prices yield the scores. This chapter discusses the scoring process, with particular attention to economic theory’s claim that prices function as accurate and meaningful market ‘signals’ which lead to so efficient an allocation of resources as to provide optimal outcomes.

Prices are said to serve this role even though they do not include considerable social and ecological costs that can exceed reported profits. Nor do prices take account of the direct and indirect savings to businesses that result from unpaid work done outside the official market economy by members of households and by volunteers, and from much else paid for by governments, including public-funded bailouts, and subsidies that again sometimes exceed reported profits. But although many costs are excluded from prices, many others of waste, duplication, ego gratification and high living are inappropriately included. (Section 2.1)

Prices, according to economic theory, are set by the ‘Law’ of Supply and Demand (LSD),[85] at least when a plethora of unrealistic assumptions hold: uniform market prices for identical goods, no expenses for tracking down or delivering them, and ‘perfect’ competition (2.2) – the last requiring not just enough buyers and sellers to avoid any having enough market power to set prices, but also rising costs with the scale of production. Only by assuming perfect competition can economists claim ‘optimal’ prices, efficient use of resources, and trickle down wealth creation. In practice, however, common situations where prices fall with the scale of production give rise to widespread dominance by oligopolies and, to a lesser extent, monopolies, which makes competition much less than perfect and thwarts the rosy outcomes it is alleged to provide. (2.3) Equally crippling to the concept, perfect competition also requires what economists call ‘rational’ behaviour but which more closely resembles ‘perfect foresight’. (2.4)

Economists nevertheless retain their horde of unrealistic assumptions because of allegiance to the idea that the general interest is achieved best by leaving people to pursue their own interests. Yet this mistaken dogma requires not just perfect competition and other unrealistic assumptions, but also scrupulous behaviour, and governments to perform crucial functions that don’t provide market players with maximised profits. Meanwhile, in the real world, imperfect market competition resembles a lottery, with success not necessarily following from efficiency, discipline or any other advantage, nor failure from their lack, and with no guarantee of efficient let alone optimal prices, outcomes, resource allocation, or trickling down of wealth. (2.5)

2.1 Rubbery Figures

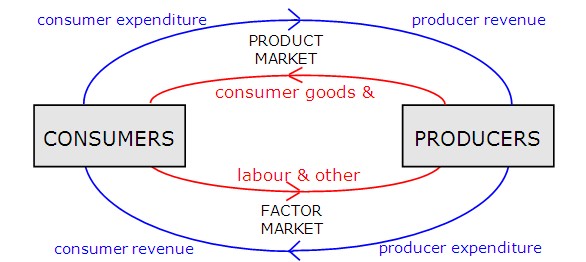

“Traditional definitions of wealth and production, of productiveness and efficiency in terms of market values… , are among the most important obstacles to an understanding of… socio-economic issues” – K.William Kapp[86]In the ‘free market’, everybody pays. Money is exchanged for goods (like food, clothes, paperweights) and for services (like psychoanalysis, accountancy, babysitting), manufactured and distributed by producers (individuals and business firms) for sale to consumers (purchasers). For convenience, orthodox (‘neoclassical’) economic theory splits the free market into two parts: in the ‘factor’ market, producers exchange money for factors, such as labour and equipment, that are needed for production of goods and services (often just called ‘goods’); while in the ‘product’ market, producers receive money for their goods.

Economists depict the process of exchange in a free market as a circular flow, between producers and consumers, through the factor and product markets (see Figure 2):[87] businesses pay money to their workers, who use their earnings to buy the goods and services produced. The money that flows out from producers to consumers returns (unless some of it is saved). However, the depiction comprises a gross oversimplification, in particular because, as discussed in the last section, it ignores the effects of profit. It also ignores how producers’ non-wage costs – such as for raw materials, parts, equipment, advertising, office rental, furniture, electricity – constitute revenue for other producers, and so cause the economic flow to also circulate within the producers box; and how second-hand sales, gifts, and so on flow within the consumers box. The full extent of the depiction’s oversimplification, however, including many other omissions, will take most of the rest of part one to detail.

Figure 2: The Circular Flow of Free Market Economic Activity

Winning or losing at the game of competition depends on how one fares at each exchange, of money for goods, or vice versa. No goods or money are created by an exchange, merely swapped in what is consequently called a ‘zero-sum game’ (whereas positive-sum games involve a net gain for at least one player, and negative-sum games, a net loss). Yet frequently, both parties to an exchange believe they have gained by it – a zero-sum game thus worth playing (at least in moderation).

Treated by economists as voluntary and mutually beneficial, exchange does not produce only winners, however. Because we compete to exchange, always winners are balanced (somewhere) by losers. As section 1.5 explained, each profit is counterbalanced by a loss for someone else sooner or later. Similarly, for some producers to win higher profits, their competitors must lose profits, and/or their customers must pay higher prices, and/or their employees must lose jobs or income due to cost-cutting changes such as automation. If employees win pay rises, either their employers lose profits, and/or consumers pay more. If consumers win with lower prices, uncompetitive producers lose business, and/or employees of competitive producers lose jobs or income. Even the discovery of an abundance of natural resources creates winners and losers: an oil strike, for example, can keep prices low for consumers, create jobs, and keep oil companies afloat, but it can also lose business for gas companies and alternate fuel and/or energy suppliers. In the game of competition, there really ain’t no such thing as a free lunch – you mightn’t pay for it, but someone does, beforehand, during, and/or afterwards. For losers, an unrewarding zero-sum game.

But no matter who wins or loses, market competition, as section 1.4 explained, compels producers to aim to maximise profits, because otherwise they risk shrinking profits and ultimate loss. Hence, producers constantly seek new profit-maximising opportunities. If, say, oil producers consistently make an average of a dollar in profits for every minute worked, but vinegar producers make profits of only ten cents per minute, then vinegar producers have an obvious motivation for abandoning their business and moving into oil production (if they can).

Profit maximisation and cost minimisation usually go hand in hand. But cost minimisation – sometimes deliberately, sometimes inadvertently – often takes the form of cost avoidance. Techniques employed in mining, forestry, agriculture, and many other economic sectors, often minimise ‘official’ costs in ways that erode, deplete, and/or in some other manner degrade the environment – degradation which may (and usually does) soon create costs for others to meet.[88]

For instance, without sufficient enforcement of government regulation, to pollute usually costs less for firms than not to pollute – so, many do. But because other people suffer from, and pay for dealing with the effects of, pollution – even, in some cases, those living far away, as when it induces acid rain – Barry Commoner’s conclusion on the matter seems unavoidable: “A business enterprise that pollutes the environment is… being subsidized by society; to this extent, the enterprise, though free, is not wholly private.”[89]

Costs avoided by being effectively transferred to others to pay are called ‘social costs’, or (more frequently) ‘externalities’. Neither voluntary nor mutually beneficial (unlike exchange), externalities “arise when the voluntary economic activities of economic agents – in production, consumption, or exchange – affect the interests of other economic agents in a way not setting up legally recognized rights of compensation or redress.”[90] Much rarer than negative externalities like pollution, positive externalities also occur when people’s economic activities benefit others without cost, as when a farmer cultivates a natural predator of pests that spreads to neighbouring farms.

Negative externalities typically involve ecological degradation: soil erosion and/or salinity… reduced biodiversity… desertification… air, water, soil and any form of pollution, including consumer litter, traffic din, and the often emetic audiovisual assaults of advertising, even “the noise generated by a new factory or the view spoilt by its construction [which] are real costs that should be taken into account in determining whether it is worth building.”[91]

For some industries, the most easily quantified externalities can comprise about fifteen percent of total costs.[92] If producers had to increase the prices of their goods by fifteen percent (or more) to pay for the externalities they create, many might find themselves uncompetitive and unprofitable. This is overwhelmingly confirmed by another estimate of “only those costs which had been properly established by authoritative studies” which indicated that “in 1994 corporations in the United States were permitted to inflict $2.6 trillion-worth of social and environmental damage, or five times the value of their total profits.”[93] This does not even take into account K.William Kapp’s suggestion “that at least some of the much-taken-for-granted economies of large-scale production and many of its apparent advantages would be partly if not wholly offset by the tangible and intangible social costs of over-concentration”,[94] such as urban congestion, gridlock, peak hour pollution, and diminished physical and mental health from over-work, under-work, and other stresses of economic competition.

It must be emphasised that externalities are not caused by lack of efficiency or productivity: higher productivity – increased output for the same or decreased input – can be achieved by adopting quicker but more sloppy, dangerous, and/or polluting methods. Rather, ecological degradation follows all but inevitably from the rules of the game: through the market’s profit-dazed eyes, screened by its single-minded, aggressively competitive tunnel-reality, mother nature seems to shamelessly flaunt her alluring ‘free’ spoils and promise quick and easy profit – so she can hardly avoid being gang-raped and left to rot.

Yet producers do not just exclude many costs of externalities from prices, they also exclude many other contributions to production. To function in the manner to which they have become accustomed, businesses depend on much activity performed ‘outside’ the market economy which, because it costs them nothing, is not included in their prices. For instance, in households with only one wage earner, the partner, usually for free, often performs most or all housework, home maintenance, child-minding, pseudo-psychological counselling, shopping, and various other duties, without which the average money-earner would have less time to spend either at his/her job or at leisure; with either option (because reduced leisure-time often results in stress and lowered efficiency), businesses would suffer – and not just to a minor extent. According to Trainer: “Some have estimated that as much as half the work or production that takes place in our society is in this non-commercial category… [T]he domestic work of housewives [may have an unpaid value of]… 25% of GNP.”[95] Almost priceless. Other unpaid formal volunteer work similarly adds to society’s direct and indirect discounting of business costs.

Producers also avoid costs through their use of goods and services paid for by society and provided by governments. Costs of production and distribution would invariably rise without roads, railways, ports, police, free or subsidised education, and other goods and services useful to business. While some might argue in response that business pays for its use of these items through taxes, the evidence indicates that it receives more than it gives.

Bernard Lietaer has made the sweeping claim that “American corporations pay less in US taxes than they receive in public subsidies from US taxpayers.”[96] More specifically, a Congress report from the 1970s estimated that the USA federal government then annually spent $100 billion on direct subsidies to business, more “than the total yearly corporate profits of all American business.”[97] Reported profits are at least sometimes exceeded by government grants, tax breaks, incentive schemes, loan guarantees, investment rebates, and wage and other subsidies. For instance, according to Trainer, the British government’s direct subsidies to business, and its indirect payments in the form of research funding, “in 1973 came to a far higher total than the 1,650 million pounds figure for profits made by private firms… [I]t would seem that business in Britain could not have made a net profit had it not received these huge transfers. One single tax write-off scheme introduced by the British government in 1974 gave 3,800 million pounds to business.”[98] Companies in most nations probably benefit from similar government generosity.[99]

Government support of business does not stop there, however. Sometimes governments fund research and development of their own, only to hand over the results to private industry gratis or heavily discounted. For example, “$155 billion of the American people’s money… went into developing atomic energy”,[100] yet in 1953, apparently satisfied with the results of its efforts, the USA government handed over the fruits of its labour to free enterprise, and atomic energy – funded by all – became another means of generating private profit – for a few.

Let’s also not forget publicly funded bailouts of ‘too-big-to-fail’ corporations – even, or especially, of those who most ardently chant that the market knows best and must not be regulated or otherwise interfered with by the state. Governments certainly came to the rescue of numerous teetering financial institutions when the Great Recession began in 2007 (no wonder with “the finance sector… making 40% of [all] corporate profits”[101]), as well as affected corporations such as major USA auto companies. But the precedent was set long ago: Lockheed Aircraft in 1971, Chrysler Corporation in 1980, and too many banks and financial institutions in the years in between and since to list here.[102]

But if, because of all this, the costs, prices, and profits of producers, though often claimed to the exact cent, seem almost arbitrary, then other factors make matters even worse.

Many costs are excluded from prices, but many others are inappropriately included. Especially for firms with market control, production need involve payments not simply for wages, equipment, transportation, and other unavoidable costs. Production ‘costs’ can also include those of advertising, public relations, political lobbying, glittery excessive packaging (discarded immediately upon unpacking to usually then turn into garbage or pollution), and much else thought by business as essential for successful competition but which necessarily raises prices.[103] Consumers also have to ultimately pay through prices (and/or taxes) for even more unnecessary unjustifiable business ‘costs’, such as payments for unduly lavish office furniture and equipment… prestigious petrol-guzzling company cars… exorbitant business lunches and dubious client entertainment expenses… jobs for the boys… Picassos and weekly lock-changes for executive washrooms… million-dollar consultancy fees for five minutes of pre-determined discussion with self-styled authorities long past their use-by dates… ‘brainstorming’ retreats and overseas ‘business’ trips that include five-star accommodation, century-old brandy, and Kama Sutra instructors… mega-tonnes of smooth marble floors and walls conspicuously adorning skyscraper lobbies of corporate headquarters… and various other forms of waste, duplication, ego gratification and high living. Let’s not forget plain incompetence either. For Big Business at least, gambles that don’t pay off, and other miscalculations, can often be covered simply by raising prices. For instance, when nuclear energy went out of fashion after the Three Mile Island accident, many plants under construction in the USA were abandoned at a total cost to energy companies of $900 million – which they then retrieved by raising electricity prices.[104]

Given that prices do not include many costs avoided while pursuing profit maximisation, but do include many unnecessary and/or unjustifiable costs, it seems ludicrous to regard prices as accurate or meaningful. Yet economic ‘science’ doesn’t settle for doing just that – it elevates prices to lofty heights of reverence usually reserved for gods…

2.2 The ‘Law’ of Supply & Demand

“The avowedly straightforward theoretical determination of price by the intersection of the two lines expressing the hypothetical possibilities of the effect on price of changes in supply and demand… does not turn out to be so simple.” – Thomas Balogh[105]Because of the way markets compete to sell and profit, prices depend, to some extent, on both the supply (market availability) of goods and services, and their demand (the financially-backed desire to purchase them): as soon will be demonstrated by examples, if demand for a good (or a specific type of labour) rises (or falls), its price also tends to rise (or fall); whereas if its supply increases (or decreases), its price tends to fall (or rise).[106]

So, plentiful supply and demand – as for water in a river district, iron ore, unskilled labour – result in low prices. Plentiful demand but little supply – as for water in a desert, diamonds, skilled labour – result in high prices. Plentiful supply but little demand – as for salt water, mud, proficiency at snoring – rarely result in market exchanges, but always at very low prices.

These tendencies, however, were elevated long ago by economists to the status of ‘law’ – the so-called Law of Supply and Demand (LSD). For about two centuries, most economists have claimed not simply that LSD sets prices, but that it determines, in an orderly straightforward fashion, stable and ‘optimal’ prices. This follows, according to a textbook because: “Price is determined by the intersection of market demand and market supply. It is only at the intersection of the market demand and market supply curves that an equilibrium exists.”[107] To explain…

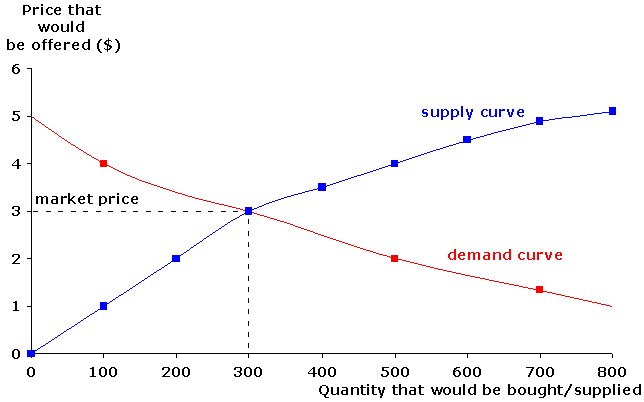

The amount that people buy of any good depends partly on its price. As an example, consider a small town in which, if bread cost two dollars a loaf, 500 loaves would sell, but at three dollars a loaf, only 300. Plotted on a loaves-versus-price graph, this and additional data might suggest a line or curve; economists call it a ‘market demand curve’, and it represents the total quantity of bread that all buyers in the market would demand depending on its price (see Figure 3). Note that to plot such a curve requires assuming, in the words of a textbook, that “the same price… is being charged to every individual in the market. Where this assumption is not appropriate, a market demand curve in the ordinary sense cannot be constructed.”[108]

Figure 3: Price Establishment by Supply and Demand

In a similar fashion, because competitive producers alter their production rates depending on what prices they can obtain in their markets, a ‘market supply curve’ represents the quantity of a good that all sellers in a market would supply depending on its price. Continuing the example, at two dollars a loaf, the town’s bakers might supply 200 loaves, but at three dollars a loaf, 300 (also see Figure 3).

Given the size of most markets, the numbers and variety of people involved, and the changing conditions each must face, rarely can market supply and demand curves – also called ‘schedules’ – actually be measured, or even estimated. Thomas Balogh, a not so orthodox economist, went so far as to call schedules “figments of the imagination”.[109] In his view: “The only observations we have… relate to price, demand and output at different historical points of time. How they are connected with each other, if they are so connected, is a Gestalt in the beholder’s eye… The shape of the curves… might in fact be so intricate as to defy mathematical handling. Their shape and position will in all probability change in time. And they are by no means necessarily independent from one another – if they are important, quite the contrary. Indeed they might be better represented by discontinuities rather than smooth curves. They are most unlikely to be linear.”[110] Despite these objections, however, schedules are usually depicted as straight lines.

Economists inevitably draw demand curves (as in Figure 3) with a negative slope (downwards from left to right) so as to agree with the alleged Law of Demand: “The quantity demanded varies inversely with relative price, other things held constant.”[111] But the law of demand “does not follow from the pure logic of choice. Its justification is empirical observation of the world”;[112] that is, in any market: “Buyers are willing to purchase more, the lower the price”.[113] Of course, small price differences may encourage no changes to buying habits, so at least parts of demand curves – to the extent that they mean anything at all – can be horizontal.

On the other hand, supply curves are drawn positively sloped to agree with the so-called Law of Supply: “the quantity supplied is directly related to the price.”[114] While the Law of Supply seems oddly incongruous with LSD’s ruling that if overall supply increases, prices fall, it is said to be justified because “sellers will offer more the higher the price.”[115] Yet this is not always true. In much modern industry, technology works most cheaply and efficiently at certain optimum levels – producing less (or more) than the optimum amount then actually costs more. Hence, producers may offer lower prices to encourage demand up to the optimum level of production, and so break the law of supply in the process. The law, broken when costs fall with the scale of production, can also fail if one producer’s actions unintentionally benefit others. For example, if one farmer cultivates a natural insect predator that feeds on plant pests, then as the predators thrive and spread, nearby landowners most probably reap some of the benefits and produce more for the same or reduced cost. They could then offer more for a lower price. But although textbooks admit that “[i]t is possible… to generate a negatively sloped supply curve”,[116] they nonetheless treat it as exceptional.

When supply and demand curves are plotted together, as in Figure 3, they intercept at a point said to represent market ‘equilibrium’; the price corresponding to that point is said to equal the actual market price. Thus, Figure 3’s market equilibrium would see 300 loaves of bread supplied and bought at three dollars each. If bakers chose to charge more than the equilibrium price, they would be left with much unsold stock, prompting discounts and a lowering of the average price. For example, the supply curve of Figure 3 indicates that if bakers charged four dollars a loaf, they would have to make 500 loaves, but the demand curve shows that only 100 would be bought at that price – hence, the 400 leftover loaves would soon go cheaply. Likewise in reverse: a price lower than the equilibrium price would lead to less loaves produced than demanded, so some people would bid up the price in order to get what they wanted in an undersupplied market. Only at the equilibrium price would the quantity supplied equal that demanded, and so only the equilibrium price is regarded as stable and able to arrange ‘optimal’ production and distribution.[117]

That two mostly guessed estimates of probably unconstructable curves allow economists to conclude that a single stable optimal market price operates should not seem surprising – as pointed out earlier, to construct the curves, a single price must be assumed. Even so, the tautological conclusion still cannot be reached without assuming zero ‘transaction costs’ (no expenses for tracking down or delivering goods), otherwise “information concerning prices and quantities will not be readily available.”[118] Even disregarding this impossibility, single stable optimal market prices cannot occur unless markets practice what is called ‘perfect competition’ – a notion which requires not only “a substantial number of potential and actual buyers and sellers”,[119] but also rising costs with the scale of production, and either perfect foresight or no change.

Each of these assumptions will be examined in more detail soon, and found wanting. As they seem unlikely to be realised in the real world – as instead, more often, individuals and businesses alike must make mistakes, must under- or over-estimate supply and/or demand – it follows that supply and demand often can be mismatched, and numerous prices may apply for any one good, none of which need be considered ‘optimal’ or remain stable. Many factors besides supply and demand – even the mood of the day – can influence prices. For instance, “a decline in price may cause panic selling and drive the price still further down, or the reverse.”[120]

So, while LSD has an influence on prices, the ‘law’ can be bent, especially (as will be detailed) by market power, or occasionally even annulled, by mass hysteria, leading to flawed and frequently delusional market signals more aptly called LSD-prices. Revolving round these often misleading market signals, the frantic chaos of free enterprise’s imperfect competition – however ordered it might seem to economic theory – also seems better described, along with capitalism itself, as LSD-competition.

2.3 ‘Perfect’ Competition

“…an impersonally determined price which applies to all and which no single seller can influence or control [is] the kind of market which the neoclassical system assumed and in substantial measure still assumes. As a rough guess, around half of all economics lectures begin with the statement, ‘Let’s assume competition.’” – John K.Galbraith[121]Early classical economists assumed the existence of ‘perfect’ (or ‘free’ or ‘pure’) competition: each market served by numerous small firms usually producing easily substitutable goods such as food and fibre, and with few businesses requiring any specialist skills to work for or to own. With perfect competition, no individual or business, however advantaged, could take charge of the market more than any other. If any tried, the market would adjust to thwart them. As John K.Galbraith explained: “If prices and profits and therefore income were exceptionally favorable, some or all producers would be induced to expand production. Some others… would be induced to enter the business, and since it was assumed that the firms were generally small and the required capital [ie. physical productive assets or money required to obtain them] of manageable size, this would be practical. The expansion in output would [via LSD] lower the market price – the price that none controlled – and therewith the resulting profit and income. This, in turn, would reduce the power, i.e., the purchasing power which the producer deployed as a consumer. Thus not only was the consumer ultimately in control, but built into the system was a powerful force, that of competition, which acted to limit or equalize income and thus to democratize that control.”[122]

Treating consumers as in charge of the market – thus enabling the market to ‘regulate’ its prices via competition – naturally leads to the conclusion that the market works efficiently and beneficially. Indeed, perfect competition, mediated by LSD, was thought to cause prices to fall as riches accumulated; rewards of capitalists would reduce, and those of workers increase, as wealth gradually ‘trickled down’ from rich to poor.[123] It was even believed, at least before the Great Depression, that perfect competition was able to ensure (almost) full employment, because anyone out of work could compete with those employed by lowering his/her wage demands.

The wondrous tonic of perfect competition (it even made the coffee) may have seemed plausible in the days of classical economics. At the time, most markets were served by small business firms, and many “goods were also easily substitutable. The yarn from one mill or the cloth from one loom was much the same as that from another. So the competitive ideal was closely approximated. Applying the test, if one producer disappeared, the effect on price was not noticeable. But even then there were always exceptions. In classical and neoclassical economics there was always the flawing case of monopoly.”[124]

The market does not regulate the prices set by a monopolist: someone with a backyard containing the only mineral spring for miles around has little or no competition, and can charge more or less any price desired.

Neither is the game of perfect competition played among oligopolies. An oligopoly consists of a market dominated by a small number of producers of similar products – such as cars, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, rubber, steel, aluminium, electrical goods, computers, oil, airlines, communication, banks, insurance, and supermarkets – who together hold an effective monopoly between them. Whenever new technology or other techniques allow costs to fall with increasing scales of production, oligopolies have tended to form…

Perfect competition requires costs to always rise with increasing scales of production[125] – for example, a baker who makes 500 loaves of bread each day would have to charge more per loaf to produce 1,000 loaves – so that producers cannot try to corner a market without their prices losing competitiveness. Some costs certainly do rise as production mounts: for instance, as the area of still available unfarmed land decreases, its cost (and consequently that of farming it) rises. But if costs fall as the scale of production increases, those first to expand can undersell their smaller competitors, and eventually control their markets, so ending any hope of perfect competition in them. And of course, most technological advances do allow more to be done with the same amount of land, or labour, and so do often cause costs to fall with increased production, thus giving rise to oligopolies, which clearly do not engage in perfect competition.

Sometimes, just two or three oligopolist companies provide half or more of all business in their field. Oligopolist firms have no need to try to become monopolists, even if able to avoid anti-monopoly government actions,[126] and even if seeing the inherently high risks and costs as worthwhile. Instead, as Galbraith put it, they “will see the common advantage in the most profitable price and the common disaster in price-cutting. So the resulting price will be much the same as with monopoly. The sense of the common or group interest allows firms, usually without any formal communication, to find the best price.”[127] Meaning best for themselves.

Once oligopolies gain control of a market, nothing is served by losing it. Producing goods with built-in obsolescence – goods designed to have limited lifetimes so that when they stop working well or at all they are likely to be replaced – helps keep business booming, especially if newer, revamped, slightly different, more ‘feature-loaded’, but at least equally obsolescent versions of the same goods are continually made available. Many oligopolist firms not only prevent their privileges from slipping, however, they often enhance them by buying out raw material suppliers, distribution and retail firms, and any other group depended upon during production or which limits control. The USA car manufacturer, General Motors, provided an extreme example of an oligopolist expanding its power: “By 1949,… [it] had been involved in the replacement of more than 100 [public transport] electric transit systems with GM buses in 45 cities.”[128]

Clearly, because monopolies and oligopolies (together referred to henceforth as ‘monoligopolies’, a deliberately ugly word) do not engage in perfect competition, the neoclassical notion of consumers instructing and controlling the market is not valid. Furthermore, because “[a]ny non-price-taking behavior… implies violation of… efficiency”,[129] monoligopolies’ price-setting abilities mean that their prices cannot be optimal.

Even so, neoclassical economists, like their classical predecessors, treat monoligopolies as exceptions to the norm and thus as not significantly affecting market self-regulation by competition.[130] Since the 1920s, orthodox economists have conceded that monoligopolist control impedes free enterprise’s purported tendency for income equalisation, yet they regard it as not significant enough (!) to have much effect on perfect competition. (Likewise, even those who have accepted Keynes’ analysis that full employment cannot be guaranteed by market self-regulation, simply advocate a little state regulation as the re-optimising cure.) Still, they retain most classical conclusions based on the assumption of perfect competition and insist on seeing competition as maybe not absolutely perfect, but perfect enough.

Neoclassical economics’ incessant commitment to a self-regulating free market seems much like a child’s desperate wish to continue believing in Santa Claus. But as Galbraith put it: “when something gets fixed in the textbooks, it becomes sacred writ.”[131] This is exemplified by Say’s Law, a mistaken nineteenth century doctrine which claimed (unlike the analysis of section 1.5) that economies always have sufficient purchasing power to afford all that they produce. The sacredness of this particular writ was fervently passed down from one generation of economists to the next as largely unquestioned dogma, only to be over-turned by Keynes’ analysis of the Great Depression. According to Galbraith: “Until Keynes, Say’s law had ruled in economics for over a century. And the rule was no small thing; to a remarkable degree, acceptance of Say was the test by which reputable economists were distinguished from the crackpots. Until late in the thirties no candidate for a Ph.D. at a major American university who spoke seriously of a shortage of purchasing power as a cause of depression could be passed. He was a man who saw only the surface of things, was unworthy of the company of scholars. Say’s law stands as a most distinguished example of the stability of economic ideas, including when they are wrong.”[132]

Because of the stability of economic ideas, neoclassical economics also ignores how, even if numerous small firms did serve most markets and costs always did rise with the scale of production, still one other significant factor would stop competition from ‘being’ perfect.

2.4 God-like Rationality

“…even if the survival of the small firm were not made difficult or impossible by the conditions of production, by the possibility of reaping high rewards through mass production and mass advertising, it would not necessarily follow that production would be, in the jargon of the economists, ‘optimal’.” – Thomas Balogh[133]Perfect competition requires not only that prices not be controlled, but also that they act as market ‘signals’ which reflect competitors’ responses to consumer demand. For prices to act as accurate market signals, the market must behave in an orderly, easily assessed, and fairly predictable fashion, thus allowing people to communicate their desires to it. This, in turn, requires people to behave rationally, to take “action well-suited to achieve… [their] goals.”[134] Indeed, according to one textbook, the “essence of the assumption of free competition is… that it is an assumption about rationality.”[135] If we assume enough rationality, we can even treat economies as ordered and predictable, a notion that led Kapp to claim that “practically the whole system of theoretical conclusions of modern economic science could be deduced from the assumption of rational economic conduct.”[136] Without such an assumption, optimality would seem doubtful if not indefinable, but also behaviour would lack consistency and so could not be modelled mathematically and (hence) predicted.

The economic orthodoxy admits irrationality exists, but they regard it as too minor to have any important impact.

Perfect competition, however, requires a great deal of rationality – considerably more than some ancient cultures expected from their gods. In Balogh’s words, a “consumer’s behaviour must not be impulsive; he must be assumed to have considered all the possible choices open to him and to have fully understood their implication.”[137] Difficult at the best of times, change makes this impossible.[138] New techniques of production or newly discovered resources, for instance, create new market signals and alter old ones, in the meantime causing (at least initially) some measure of consumer ignorance and uncertainty. As long as things change, and especially as the rate of change continues to mount, people cannot know all their choices – not unless their rationality more closely approximates precognition or what Balogh called “perfect foresight”. Without perfect foresight, even rational people bereft of impulsiveness can experience uncertainty, risk, or just plain ignorance about market opportunities, and so can “rationally react to the same sort of situation in different ways”.[139] In which case, prices do not act faithfully as clear market signals ultimately reflecting consumer demand, but simply as the chaotic end-product of market competition.

In effect, neoclassical economic theory treats people as mechanistic and robotic, faithfully repeating the same behaviour quantified in ‘economic laws’. This approach encourages the belief that people can be influenced deterministically, in accordance with those ‘laws’, by an adjustment of appropriate economic parameters such as the money supply. But on planet earth, as Balogh pointed out: “So far from rational expectations being the norm, undue optimism and pessimism alternate and cause untold harm.”[140] Many examples could be given, but the unpredictable heaving and plummeting of stock markets around the world best demonstrates the considerable influence of irrational economic behaviour.

So, even ignoring its requirements of numerous small firms serving markets and costs always rising with increased production, perfect competition that involves prices which accurately reflect consumer demand requires the impossible: either rationality equal to god-like perfect foresight or an absence of change. Yet without perfect competition, full employment, trickle-down income equalisation, and other ‘optimal’ results do not follow.

So why has neoclassical theory held onto such unrealistic assumptions? Because they have a quasi-religious faith in market competition that compels them to do so…

2.5 The Invisible Hand

“…the theory now called ’neoclassical’’… explains how demand is determined by the urgency of consumers’ wants and how land, labour, capital and entrepreneurship receive, with perfect impartiality, neither more nor less than what they have contributed to the productive process. Harmony of interests and complete social justice were thus assured.” – Thomas Balogh[141]Economists treat the idea that market competition ‘optimally’ regulates prices with almost religious reverence. According to one textbook: “As astronomy has Newton’s principle of universal gravitation, and biology Darwin’s principle of evolution through natural selection, economics also has a great unifying scientific conception. Its discovery was, like Newton’s and Darwin’s, one of the most important intellectual achievements of humanity.”[142] This “great unifying conception” claimed that, left to pursue their own interests, people are often “led by an invisible hand to promote”[143] the general interest.

This idea of a guiding Invisible Hand was conceived by Adam Smith who popularised it in his economic treatise, The Wealth of Nations, published in 1776. Smith, sometimes called the father of free enterprise, believed that, generally, left to themselves and the rule of “natural liberty” (meaning the freedom to pursue self-interest), people behaved in ways that improved society; the greater the effort made for self-betterment and the more competitive the striving, generally the greater (more optimal) the public good.

Smith’s belief followed essentially because of LSD. Putting Smith’s reasoning into what it calls “more modern language”, a textbook explains it this way: “Each person will be motivated by rational self-interest to employ the resources under his control wherever he can get the highest possible price. But high prices reflect scarcity of supply relative to intensity of consumer demands. Hence the private incentives will work continuously to overcome scarcity and meet consumer demands, i.e., to direct resources to the employments most suited for satisfying consumers’ desires.”[144] With LSD, Adam Smith’s Invisible Hand can be clearly seen (sic).

By assuming the presence of an Invisible Hand, orthodox economists can hardly avoid concluding “that the economy is an integrated system whose behavior follows scientifically determinable laws… We owe to Smith the conception of the market economy as a self-regulating mechanism, harnessing as motive power the self-interest of participants, yet so integrating their activities that each is led to serve the desires of his fellows.”[145]

However, although Smith “was ready in the main to allow the public good to rest on ‘the natural effort of any individual to better his own condition’”,[146] he qualified his claims about self-regulating free enterprise considerably more than the above suggests. As Keynes put it: “the conclusion that individuals acting independently for their own advantage will produce the greatest aggregate of wealth, depends on a variety of unreal assumptions… For economists generally reserve… for a later stage their analysis of the actual facts.”[147]

For Smith, the Invisible Hand would bless free enterprise with optimality only if three (unreal) conditions were fulfilled.[148]

Firstly, perfect competition must rule, which the last section explained is not the case.

Secondly, an Invisible Hand requires not simply perfect but scrupulous and morally restrained competition. A sizeable requirement indeed, unless you have a tendency to believe in it beforehand. As Kapp put it, the Invisible Hand depends on Smith’s “presupposition of the existence of a natural moral law which would induce the prudent man to improve himself only in fair ways, i.e. without doing injustice to others.”[149] Keynes likewise explained that “Smith’s advocacy of the ‘obvious and simple system of natural liberty’ is derived from his theistic and optimistic view of the order of the world, as set forth in his ‘Theory of Moral Sentiments’ [1759], rather than from any proposition of political economy proper.”[150] In other words, neither the Invisible Hand, nor the scrupulousness it depends on, have been justified, merely postulated. Furthermore, assuming scrupulousness effectively pre-ordains the end result claimed, that competition provides optimal results. A case of circular reasoning.

Even if, for the sake of argument, we assume perfect and scrupulouscompetition, although prices might reflect consumer demand, still – and crucially – they need not express the relative urgency of needs. In the “more modern language” of the textbook, producers chase high prices – or more accurately, high profits – which reflect low supply and/or high demand; but because need is not demand unless backed up by money, producers can usually make more profits by ignoring the needs of the poor and kowtowing to the desires of the rich – by building Mercedes for the Mercedes-less rather than homes for the homeless, by pursuing medical research that panders to the vanity of the rich rather than curing diseases of the poor, by stockpiling mountains of excess food in the First World while the Third World starves. Putting it into even more modern – and more accurate – language, because market economies are hooked on LSD, they are deafened by the hallucinatory sound of money talking, and so pursue profits and cash flows, not the satisfaction of needs. Lacking money and (consequently) demand, the poor cannot offer business any chance of maximizing profits, so their needs take a back seat to the mere desires of others. Work of great need is sacrificed in lieu of work that makes great profits.

Hence, even an impossibly scrupulous, perfectly competitive market must result in a mixture of privilege and suffering – clearly not an optimal result. Furthermore, the inevitability of loss and the presence of losers adds to the pressures and stresses associated with competition, and so encourages abandonment of whatever moral restraint may operate. Even so, to talk of optimality at all without defining it in terms of satisfaction of need (rather than of financially-backed demand) makes about as much sense as roller skates for squids. In Balogh’s words, if “relative profit opportunities could not express social urgencies… [then] the ‘best’ or most efficient production would become uncertain if not meaningless”.[151]

The failure of even impossibly perfect, scrupulous competition to guarantee optimality because of the difference between demand and need is related to Smith’s third and final condition for the Invisible Hand: that governments maintain defence, justice, public works, and other economic affairs which, though desirable, do not provide commercial competitors with much or any profit. This amounts to more than might be thought. For example, imagine trying to run a lighthouse as a business. How could it be ensured that all signalled ships paid for the service? Lighthouses are traditionally used as an example of public goods, those that are “(or may be) used concurrently by many economic agents.”[152] TV or radio signals also comprise a public good, but they can be ‘scrambled’ to exclude non-payers from receiving them; although this costs the community in resources, it does allow profits to be maximised. But many public goods do not allow profits to be maximised, and so often become the responsibility of governments. In a textbook’s words: “Government provision is inevitable only for those public goods for which exclusion of non-payers is unfeasible.”[153] Yet even with this qualification, Smith’s original conception of the Invisible Hand clearly claims ‘optimality’ only for a limited domain involving maximised profits – elsewhere the market need not serve the community at all, let alone optimally.

Although the assumptions necessary for its existence simply don’t hold, nevertheless the Invisible Hand has been retained in economics. Still the textbooks claim that “the market system… harnesses individual self-interest to achieve a kind of mutual co-operation in the face of scarcity.”[154] The evidence against such a conclusion is discounted: according to Kapp, “phenomena which upset rather than furthered the assumed tendency toward balance and harmony were seen as atypical exceptions or minor disturbances… [Over time,] the scope of economic science… was more and more adapted to the original (normative) aim of demonstrating not only the existence but the superiority of the ‘system of natural liberty’ over alternative forms of economic organization.”[155] Indeed, again according to Kapp: “There is not a basic concept of neo-classical economics which does not in one way or another reflect and at the same time serve the purpose of demonstrating the alleged social efficiency of the market economy.”[156] And this has happened despite misgivings by classical luminaries like Malthus and Ricardo who thought the Invisible Hand much less than fully reliable and who eventually concluded that some people lose more than gain from free enterprise competition and technical progress.[157] Similarly, according to Keynes: “Some of the most important work of Alfred Marshall… was directed to the elucidation of the leading case in which private interest and social interest are not harmonious. Nevertheless, the guarded and undogmatic attitude of the best economists has not prevailed against the general opinion that an individualistic Laissez-Faire is both what they ought to teach and what in fact they do teach. Economists, like other scientists, have chosen the hypothesis from which they set out, and which they offer to beginners, because it is the simplest, and not because it is the nearest to the facts.”[158]

Yet whatever capitalism’s apologists insist, clearly competition is not perfect and does not produce optimal results, just winners and losers. So even some textbooks have to admit that “the Invisible Hand is too good to be true! There are many ways in which things can go wrong. Indeed, a large portion of modern economic analysis has taken the form of exploration of conditions leading to failure of the theorem.”[159] Some of that analysis not only earned Joseph Stiglitz a ‘Nobel’ prize but forced him to conclude that “one of the reasons that the invisible hand may be invisible is that it is simply not there.”[160] Consider one simple case, provided by Knut Wicksell,[161] concerning a situation where existing retail firms adequately serve consumers. If another retail firm opens, greater competition results (more numerous firms). Yet unless the number of consumers also increases, the same business must be spread across more stores. Hence, some store(s) must lose business, perhaps enough to warrant closing down. So, extra competitiveness in this example, prompted by the Invisible Hand’s free pursuit of self-interest, does not increase optimality as the dogma claims should happen – instead, it disadvantages some people and utilises resources inefficiently.

Clearly, market economies do not engage in perfect competition or use optimal prices that ensure efficient resource allocation. Rather, actual LSD-competition instead resembles a lottery. As section 1.5 explained, the market cannot buy all goods produced for the profit-inclusive prices charged without going into more and more debt, so some goods must at some stage remain unsold, however efficiently they might be produced. Blind faith in an Invisible Hand might motivate the claim that efficient producers will sell their goods, and the inefficient lose, but nothing guarantees this in the real world, where hands are not only always visible but also often quicker than the eye. Efficient businesses can lose because of actions of more established, more powerful, yet less efficient competitors. Inefficient businesses can profit because of monopoly or a lack of more efficient competitors or vapid fad.

And so, economic success need not follow necessarily from efficiency, discipline, skill, or any other advantage – nor failure from their lack. The ideal that anyone with an idea and perseverance can prosper sounds enticing, but you can do everything right and still, if someone else does it with more luck, you will fail simply because not all can win. Even if you win for a while, every winner always retains a chance of joining the losers: you could fail through no fault of your own when the next recession hits – and recessions happen inevitably because the rules ensure that someone is losing and/or going into debt all the time. In economies ruled by competition for profits, there can be no security for anyone, and no guarantee of efficient let alone optimal outcomes or resource allocation.

One thing the Invisible Hand has produced: a great deal of very visible ejaculate in the form of modern economic theory. To better understand why capitalism has its own professional cheer squad, ever ready to heap praises on it for its alleged success, and to find pretexts for its frequent failures, further details about the ‘science’ of economics must be given.

Please prepare yourself – you are about to enter the land of extremely weak excuses…

Chapter 1 Chapter 1 |

Chapter 3 |