Chapter 5

Profits, Jobs & Holy Growth

“…the complacency with which Laissez-Faire capitalism was expounded especially by its economist-flag bearers, was not vindicated. The system as such has not been stable; it has not produced equality, whether nationally or internationally; it has done little or nothing to mitigate the privileged position of the richer areas by a more equitable international distribution of wealth. There has been no automatic tendency for countries (nor regions within countries) of unequal economic strength to become more equal merely through the mechanism of trade or growth.” – Thomas Balogh[304]This chapter looks at the ‘macro’ effects of L$D-competition, beginning with how the compulsion to grow motivates the creation of an endless amount of frequently unnecessary, often counter-productive, even self-destructive activity: only about thirty percent of work in modern economies produces real wealth, while forty percent cleans up the mess made by the rest, with the minority who do the essential work often rewarded far less than many of the majority devoted to producing no real wealth whatsoever. (Section 5.1)

And yet, despite their compulsive need to grow, and the efforts made to try to ensure this, L$D-competitive economies periodically contract into recession, casting many participants aside in the wake. Indeed, business cycles of boom and bust cannot be avoided as long as we L$D-compete. (5.2)

Governments try to keep L$D-competition growing smoothly, but because they remain part of the market, because they are inextricably tied to the private sector by mutual self-interest, they cannot play the role of the market’s fuse-like optimiser. (5.3) Certainly, the methods they use to try to regulate the market – fiscal and monetary regulation of aggregate demand – often just don’t work, for a multitude of reasons, but principally because they require a series of often contradictory juggling acts. (5.4)

L$D-competition has no way of avoiding its unwelcome outcomes, because they follow irrevocably from its game rules. As a result, despite claims of orthodox economic theory, market economies do not involve equilibrium and have no neat circular flow. Instead, their interdependent parts engage in a perpetual contest to direct onto themselves as much as possible of a complex and turbulent, yet coagulated, eddy-filled flow of liquidity – a contest which invariably leaves some fully immersed if not drowning but others bone dry (5.5).

5.1 Employmentism[305]

“If we continue to believe that the goals of the industrial system – the expansion of output, the companion increase in consumption, technological advance, the public images that sustain it – are coordinate with life, then all our lives will be in the service of these goals. What is consistent with these ends we shall have or be allowed, all else will be off limits.” – John K.Galbraith [306]Near the end of section 1.4, it was explained how market competition’s drive to maximise profits encourages cost reductions which often involve less labour, and how fewer workers with less money to spend contradictorily risks reduced consumption, profits and growth. So, to truly maximise profits and growth, new jobs have to be perpetually created to replace those lost. And so, competitive market economies must aim for ever more work, which, as the last section mentioned, requires new consumable wants to be contrived. Hence, the game can have no end, and the economic engine cannot be turned off, instead it drives the vehicle round in endless circles until it must grind itself into the ground or run out of fuel.

The compelled invention of contrived wants and ever more work may comprise the real growth industry, but invented work need achieve nothing especially useful. Frivolous goods with built-in obsolescence, toothbrushes with inbuilt brushstroke counters, office furniture too expensive to sit in – whatever – just so long as they make a profit (even a short-term one) and so help the system survive and, preferably, grow. For the same reasons, more of what used to be done for pleasure is now done instead for money. Now we have entertainment, sport, recreation, and sex industries. One day, perhaps, a slumber industry will pay people to sleep (perhaps with the slogan “at least it keeps them off the streets”).

It can’t be helped, at least not as long as L$D-prices measure manipulated financial-backed demand rather than genuine need, and the market values profit-making activity over and above scarcity-minimising and/or life-improving and/or wealth-creating work. Nevertheless, profitable but otherwise useless activity now tends to dominate…

Fuller estimated that “70 percent of all jobs in America and probably an equivalently high percentage of the jobs in other Western private-enterprise countries are preoccupied with work that is not producing any wealth or life support – inspectors of inspectors, reunderwriters of insurance reinsurers,… spies and counterspies, military personnel, gunmakers etc.”[307] To this overly brief list, I would add most or all work in advertising, marketing,[308] red-tape-binding, consultancy, administration, lobbying, stockbroking, employment counselling, currency and other financial trading, cosmetic surgery, real estate, commercial law, research of the bleeding obvious or utterly useless, multi-level management and supervision, door monitoring, and various other jobs that do not create wealth nor serve any genuinely useful purpose except to prompt more spending and help make (or, in government circles, redistribute) profits.

Fuller’s estimate, made in the 1970s, can be treated only as approximate, but most likely also as conservative, because of subsequent productivity increases, and growth in financial and other service industries. However, much modern contrived work doesn’t just seem merely unproductive or unnecessary, but also counter-productive, even self-destructive: as section 1.4 mentioned, perhaps forty percent of all money spent cleans up the mess made by the rest, with the environment treated as “a garbage dump and a get-rich-quick scheme.”[309] Indeed, the notion of the market optimally allocating resources can only be viewed as a mistaken article of faith when one realises that “half to three quarters of annual resource inputs to industrial economies are returned to the environment as wastes within a year.”[310]

And so, forests die for memos in quadruplicate giving inaccurate details about subjects of no relevance to people who aren’t interested. Toxic waste and littered packaging spew forth so some can own lights that switch on and off by themselves, or toy penguins which sweep up table-crumbs. Chemical weapons capable of wiping out the biosphere proliferate, only to become victims of treaties demanding their destruction (at fifty times the cost of production[311]). Health and environment degenerate because of pollution from gridlocked cars ‘travelling’ between homes and distant workplaces that many drivers would prefer not to have to attend. Inadequate leisure-time and crèche-dumped quality-time-unsatisfied children languish because of double-income stress. Corporate power games and promotional struggles sell out friendship, self-respect, and individuality. Lives waste away from workaholism or alternative addictive states sought for escape from nine-to-five humdrum. Relentless L$D-competition transforms “I was just doing my job” into a universal excuse for collective idiocy – even bestowing clear consciences to exporters of hi-tech weaponry and torture equipment banned in the exporting countries, yet sometimes sold even to nations rife with human rights violations and/or links to terrorism. If we did not ‘have’ to keep the economic flow growing, surely at least seventy percent of jobs in the developed world would not be ‘needed’. But instead we keep on inventing new, futile, frivolous and/or dangerous forms of employment. Mundanity ’til Friday (or, nowadays, Sunday).

Naturally, too, L$D-competition ensures that the monetary reward for work has much less to do with its actual need than its capacity to assist in the making of profits. So, necessary but comparatively easily supplied work to produce food, housing and clothing, due to its inability to maximise profits, often returns low L$D-pay. In contrast, other activities akin to recreational hobbies in art, music, sport, literature, film and TV – sometimes with intrinsic value but never serving fundamental needs – often receive ludicrously high rewards due to their profit-maximising capacities… as do other unproductive jobs in marketing, legitimised gambling, pen-pushing, paper-shuffling, post-15-minutes-of-fame speaking engagements, finance – especially speculation – and much much else. Perfectly exemplifying the disconnect, according to Das: “In 2007 the combined remuneration at the five major Wall Street investment banks alone exceeded the world’s total foreign aid budget of $850 billion.”[312]

The cost of invented work though, whatever its true value (or lack of), must be covered by a price. Even if work is not invented quickly enough to sustain growth, still someone pays – via higher taxes or reduced government services to cover extra unemployment benefits, greater crime rates (and consequently bigger insurance premiums), and a less cohesive and compassionate social fabric. One way or another, rich must subsidise poor; winners, losers; and those with jobs, the unemployed.

Even so, despite all the efforts to contrive wants and create jobs, to maximise profits, and above all else to sustain growth, remarkably, the efforts periodically fail…

5.2 The Manic Depressive Market

“…anything which interferes with the processes of production necessarily interferes also with those of consumption… [W]hen a man is thrown out of work… his diminished spending power causes further unemployment amongst those who would have produced what he can no longer afford to buy… If you buy goods, someone will have to make them. And if you do not buy goods the shop will not clear their stocks, they will not give repeat orders, and someone will be thrown out of work.” – John Maynard Keynes[313]L$D-competitive economies are never static: often they grow, but sometimes they shrink. Alternations of expansion (growth) and contraction (often, somewhat euphemistically, referred to as ‘negative growth’) have been termed the ‘business cycle’.

During expansion, expenditures, demand and consumption rise, and so businesses, sensing increased profits, often further expand production and hire extra staff, causing unemployment to reduce and/or consumption to increase further. Yet despite this positive feedback process, which ostensibly seems capable of keeping expansions going forever, competitive economies somehow flip over to a contraction phase, during which expenditures, demand and consumption fall, which prompts businesses to jettison staff or pay them less or close down altogether – all options that cause unemployment to grow and/or demand to reduce further, thus potentially creating another vicious circle.

Of course, growth is seen as desirable, but mostly because of the undesirable consequences of contraction. Periods of six months or more of sustained negative growth are called ‘recessions’, or if particularly severe or protracted, ‘depressions’. When recessions and depressions end, the initial period of positive growth is called the ‘recovery’ phase, and the peak of expansion that follows it, if involving near-capacity production, is called a ‘boom’. Recessions and depressions are also sometimes called ‘busts’, and the business cycle, ‘boom ‘n’ bust’.

Most economies bust at least once a decade. In the eighty years immediately following World War 2, the USA, the world’s richest nation over the period, experienced no less than eleven recessions – in 1948-49, 1953-54, 1957-58, 1960-61, 1969-70, 1973-75, 1980-82, 1990-91, 2001, the ‘Great Recession’ of 2007-09, and 2020. Depressions occur much less frequently: the last one (the Great Depression) occupied most of the world for the entirety of the 1930s, coming four decades after the previous one in Australia and Britain, and six decades after the previous USA depression.

Busts sometimes affect only one or a few countries, but more often they spread from one to another, especially when severe or originating in economically strong nations. The weakest, of course, feel most the adverse effects. But in depressions, L$D-competition’s losers proliferate and dilute the economic flow so much that even most winners are inconvenienced (although, as always, some of the more astute rich grow richer by plundering the cheap spoils made available by others’ hardships).

That L$D-competition self-regulates itself optimally by repeatedly falling in a heap may seem absurd, but at least until the Great Depression, the dominant economic opinion made just that claim. At first, bewildered economists blamed ‘external’ causes: sunspots that impoverished harvests, inept government intervention, wars and trade breakdowns, stock market crashes, exceptional changes to money supplies (such as the retirement of the USA greenbacks just prior to the depression of the 1870s), even “inexplicable waves of psychological pessimism… [that] cause temporary panics during which money is hoarded and credit is withheld.”[314] But “inexplicable” and/or “external” causes allow no general design for prevention or cure, and so economists claimed that bust economies had to correct themselves – meaning self-regulation. The same conclusion followed when treating business cycles as ‘normal’ or inevitable rhythms, in which economic weaknesses or ‘maladjustments’, picked up during booms, could only be purged by busts: any attempt to hasten the end of ‘bad’ times or coax the ‘good’ could interfere with the economy’s self-healing capacities, and perhaps even cause the maladjustments to be retained into the next cycle.

For all of the nineteenth century, the orthodox viewed recessions as possibly exceptional but always necessary self-regulated purgings of the economic system. It was not until early in the twentieth century, in England, that John Hobson proposed an alternative explanation: that recession resulted from insufficient consumption caused by higher profits. Hobson argued that, during expansions, profits rise faster than wages, which leaves already high-income profit-makers with a larger share of the total national income; because, generally, the higher the income, the less inclination to spend it all, the success of profit-makers in expansions reduces a nation’s total inclination to consume, which turns boom into bust. However, the ‘underconsumptionist’ reasoning of Hobson, and many others to follow him, failed to take into account that investor demand may compensate for lower consumer demand. Underconsumptionists also could offer no practical advice for avoiding busts, merely calling for higher wages to raise consumer demand and so maintain profits and the boom – fundamentally flawed advice because higher wages also mean higher costs and potentially reduced profits.

‘Overinvestment’ theorists agreed with Hobson that the higher profits of an expansion sow the seeds of a subsequent bust, but claimed the seeds sprout because of too much investment, not too little consumption. Higher profits allow greater investment, which prompts the creation of new production equipment, but this raises demand for, and prices of, factors used in producing the goods, including labour and raw materials. Hence, by the time an economy booms, prices of consumer goods do not rise as quickly as their costs, and so, profits reduce – which decreases investment – which causes the growth in employment, income, and consumption to fall – which reduces profits and investment further – and so on – eventually increasing unemployment and turning boom into bust. The opposite process later reverses the cycle. But the many overinvestment theorists proved just as impractical as underconsumptionists when it came to advising how to prevent recessions: costs, especially wages, they said (contrary to Hobson), should be kept as low as possible, even though this would keep consumer demand low, and thus retard the growth of profits. Not until the Great Depression and the work of Keynes did economics progress beyond the joint impasse of underconsumption and overinvestment.

In 1936, in the depths of the Great Depression, John Maynard Keynes, a well-known and respected British economist, published his “General Theory of Employment Interest and Money”, in which he refuted century-old dogma that had originated with “J.B.Say, the French counterpart and interpreter of Adam Smith… Say’s law, not a thing of startling complexity, held that, from the proceeds of every sale of goods, there was paid out to someone somewhere in wages, salaries, interest, rent or profit (or there was taken from the man who absorbed a loss) the wherewithal to buy that item. As with one item, so with all. This being so, there could not be a shortage of purchasing power.”[315]

According to Say, even savings could not reduce purchasing power, because they allow a compensating level of investment. If investment fails to keep up with savings, according to Say, the problem resolves itself in a manner typical of equilibrium theory: savings surpluses reduce consumer spending and demand – which lowers interest rates and prices – which stimulates investment and consumption – which reduces and discourages savings, and brings them into line with investment. Similarly, Say viewed unemployment as sure to lead to a reduction in wages sufficient to encourage the hiring of the unemployed; because of “always sufficient” purchasing power, wages would not rise until nearly full employment had been achieved. Say’s L$D-inspired visions of economic heaven, however, did not materialise in the Great Depression, when investment, savings, wages and prices all fell, and unemployment rose to unimaginable heights – in Britain, one person in three.

In essence, Keynes’ overturning of Say’s law centred on the fact that “since savings and investment were by different people and institutions, there was no good reason to expect them to be equal.”[316] In an economy’s expansion phase, wages, profits, consumption, production, employment and investment all increase; but as underconsumptionists suggest, sooner or later, consumption fails to keep up, and savings grow. Contrary to Say, however, Keynes maintained that savings need not all be invested – instead, as a precaution, they could be retained for the sake of increased liquidity. Of course, retained savings reduce aggregate demand and consumption, which decrease production and employment. Keynes agreed with Say that interest rates, wages and prices then all reduce, but Keynes claimed this in no way guarantees a return to full employment. Lower interest rates might merely reinforce liquidity preferences; lower wages need not be accepted, at least by those who can instead rely (for a time) on savings; and hence, lower prices need not increase consumption or investment. By the time savings reduce out of need to a level matching investment, wages, prices and production could reduce considerably, and unemployment could rise dangerously high – not a full employment but an ‘underemployment’ equilibrium.

Keynes’ conclusion, that free markets do not always optimally self-regulate, forced him to argue for governments to regulate aggregate demand by spending in ways that compensate for changes to consumption and investment. And his methods (to be detailed in the next two sections) worked – for a while. Ultimately though, history since Keynes has shown that government regulation cannot avoid business cycles, only soften their blows (even fully regulated Soviet socialism could not avoid them[317]). However, not just Keynes’ remedy but also his explanation seems flawed: it treats inadequate demand as sure to lower production, employment and prices, whereas recent recessions have been accompanied by rising prices.

Many attempts have been made since Keynes to more fully explain business cycles, and according to Howard Sherman: “Almost all economists agree that the crisis leading to a recession or depression is caused by a profit squeeze.”[318] Sherman’s own detailed analysis of business cycles[319] – based on data for USA cycles between 1947 and 1975, and synthesising underconsumption and overinvestment with Marx and Keynes – does explain simultaneous recession and inflation; my own emphasis has been placed on the summary of it which follows.

After declining during a contraction, profits stabilise at a recession’s trough, whereas wages, costs and prices all continue to fall (or else, if cost-push forces have not been quelled by reduced demand, they grow more slowly); but also, as per Hobson’s logic, proportionately more income is left in the hands of workers than in the earlier stages of contraction. So, with the economy overall having a rising inclination to consume, and with a negative (or else a diminishing positive) rate of growth of wages and costs, businesses are enticed to make use of equipment left idle in the recession and produce more continuously – which reduces their costs and so increases their profits. The expansion begins. Greater consumption and profits encourage increased production, investment, and eventually, once all idle equipment is re-functioning, employment – which increases income and, with it, demand and consumption – which further increases employment, production, profits, investment, and soon, prices (or else allows them to grow even faster). The economy booms. But aggregate demand has limits and cannot forever grow as or more quickly. Rising investment demand raises the prices of labour and, even more so, non-labour costs, especially raw materials. Higher wages lead to higher savings, which, with rising profits, reduce the economy’s overall inclination to consume. The combination of tapering consumer demand and rising costs slows the growth of consumer prices until they rise more slowly than costs – so profits taper off and fall – which reduces investment – which lowers income – which lowers demand – which lowers production. The expansion turns into a contraction: reduced production lowers employment, which further reduces demand, and eventually, wages, costs and prices (or else slows their growth rates) – lower wages and costs then cause profits to fall more slowly and eventually taper at the recession’s trough – at which point, the economy is doomed to repeat the sequence just described.

The interplay of many economic factors to create the business cycle is also greatly affected by the exercise of market power (particularly by groups like OPEC), by “irrational optimism and pessimism,… foreign trade and investment,… postponement or hurrying of major inventions and innovations,… depreciation and replacement cycles,… panics and expansions in money and credit,… some kinds of government intervention, and… inventory cycles.”[320] The recession of 1990-91, for example, saw profits fall because of high interest rates and debt levels following pervasive financial deregulation in the 1980s, a relatively brief oil price spike in the second half of 1990, and cutbacks in military expenditures due to the end of the cold war. By contrast, the Great Recession of 2007-09, as mentioned in section 4.4, followed after rising interest rates led to falling house prices, which prompted widespread defaulting of mortgages, the demise of mortgage-backed securities, the consequent collapse of many financial institutions, and the stock market plummeting and credit crisis this triggered – all of which led to reduced lending to businesses and lowered demand, which eroded profits. In both cases, resultant unemployment was aggravated by increased automation, computerisation, off-shore migration of facilities and labour, and other ‘productivity improvements’ which had boosted profits and economic growth more than job growth. The recession of 2020, on the other hand, resulted from the COVID-19 pandemic prompting governments to restrict social interaction including employment, thus immediately reducing profits and income for many.

The interplay of many factors nevertheless cannot hide how profits have the most fundamental influence on the business cycle: rising profits cause bust economies to limp into expansion; tapering then falling profits contract booming economies into recession. However, because aggregate net profits cannot happen without mounting debt (as section 1.5 explained), financial markets also play fundamental roles.

In distinct contrast to neoclassical theory, Hyman Minsky argued that financial markets have major influences on the business cycle. In his “financial-instability hypothesis”, Minsky contended that the swelling profits accompanying economic growth sooner or later prompt ‘speculative euphoria’, which results in riskier investments through ‘innovative’ finance, so that “over a protracted period of good times, capitalist economies tend to move… to a structure in which there is large weight to units engaged in speculative and Ponzi finance.”[321] Eventually, the process peaks, the Ponzi investments can no longer be sustained and therefore suffer defaults, credit is tightened, and panic may set in, all of which are “likely to lead to a collapse of asset values.”[322] The Great Recession of 2007-9 provided an egregious example of the outcome.

However, Minksy emphasised that: “In spite of the complexity of financial relations, the key determinant of system behavior remains the level of profits.”[323] Debt enables profits (which foster growth) but the pursuit of profit motivates and requires (as per section 1.5) the creation of debt – therefore profit has the primary role. Consistent with this, Minsky contended that the instability of business cycles follows irrevocably because of the “internal dynamics of capitalist economies” (though cycles can be moderated by “the system of interventions and regulations that are designed to keep the economy operating within reasonable bounds”).[324]

So, although profits rise or fall depending on the behaviour of many factors, especially debt and interest rates – but also wages, costs, foreign competition, and others mentioned above – nevertheless, because people L$D-compete for profits (and for most all else), no balance can be reached. Profits must rise and fall, and market economies – inherently unstable – must boom and bust.

In modern affluent economies, which maximise profits by contriving wants and work, profit-makers may lack sufficient new products in which to invest; then, profits can act much like Keynes’ notion of retained liquidity, rising too quickly to be put fully to use, and instead clogging the economic flow and slowing expansion. Alternately, inadequate contrivance of new wants may prompt profits to be invested, as Minsky argued, in risky, non-wealth creating, speculative ventures, leading to fragile bubbles[325] – especially if recent success has encouraged more casual, even careless attitudes towards investment, reduced or less enforced regulation by government, and/or greater lending to those with few assets and, thus, little credit-worthiness. All of these profit-related factors played their part in causing the Great Recession, but likely they influence all recessions to some extent.

The same factors also play their part in turning recessions into depressions. Keynes deduced that the Great Depression began because of reduced demand. Some have suggested demand fell because of high interest rates squeezing profits. Others have claimed that economic difficulties ‘transmitted’ to the whole economy from troubled sectors like agriculture, where poor harvests especially in 1926 left many barely usable farms in the hands of bankers. Galbraith proposed merely that “business concerns, in the characteristic enthusiasm of good times, misjudged the prospective increase in demand and acquired larger inventories than they later found they needed. As a result they curtailed their buying, and this led to a cutback in production.”[326] Galbraith also mentioned that, after years of rising profits, investment might have “failed to keep pace”, which also would have resulted in “falling total demand reflected in turn in falling orders and output.”[327]

Undoubtedly, as in any recession, many factors helped squeeze profits and reduce demand, but the contraction that began near the middle of 1929 at first seemed no different to earlier short contractions such as in 1924 and 1927.

Monetarists (naturally) have argued that poor government management of the money supply turned the 1929 contraction into the Great Depression: instead of growing to compensate for falling demand, as monetarists advise, the money supply fell in the USA by one-third between 1929 and 1932. Yet in Britain and Canada, central banks expanded the money supply from the start, and bank failures were kept to a minimum, but still these countries were gripped by depression as much as or more than the USA.[328]

Keynesians (also naturally) claim that inept fiscal policy had a greater effect than inept monetary policy: after an initial fall in investment in 1929, dwindling consumption reduced tax revenue, which prompted the USA government to raise tax rates, which reduced consumption and growth even further.[329]

The ineptitude of official policy certainly seems significant, but other entwined factors seem just as or more important – the stock market crash especially. All great periods of speculation end, and usually tumultuously – the nature of speculation ensures it. As section 4.4 explained, anything which seriously interrupts the rise of a stock market also weakens the expectations of the market’s players, without which the rise cannot be maintained. Hence, when demand reduced in the middle of 1929, this only lit a Minskian fuse already in place (and with so much bull in the air, an explosion had to occur). That the market responded to its serious interruption by converting undue optimism to excessive pessimism, and confidence to panic, merely demonstrates the inherent insecurity of securities markets. But because lowered stock values mean less capacity to spend, cheaper assets, and decreased liquidity, the stock market crash bled dry corporations and those who depended on them for proceeds (such as the many holding companies and investment trusts that had earlier proliferated). Thus, with the bursting of the speculative bubble, much of the wealth claimed by the rich was wiped off the board.

The loss of income resulting from lowered demand and the stock market crash turned numerous loans bad, and also forced many people to use their savings; consequently, the liquidity of banks, many of which had also lost money on the stock market, partly or wholly evaporated. The banking structure of the time seems somewhat fragile, “implicit in the large numbers of independent units. When one bank failed, the assets of others were frozen while depositors elsewhere had a pregnant warning to go and ask for their money. Thus one failure led to other failures, and these spread with a domino effect.”[330] With less money about, fear motivated some people to keep a supply of cash hidden away at home, which deprived others of its turnover, and which reduced demand and bank liquidity further. Eventually, to entice sales, many producers felt they had no option but to lower prices, setting in a period of deflation, which further aggravated the situation.

The avalanche of bank failures also had the effect of a large reduction in foreign lending. Foreign demand had contributed significantly to the USA’s aggregate demand during the 1920s, and loans had been freely granted to foreign debtors to cover their trade deficits. Once the loans stopped, and the depression spread from the USA to just about everywhere else, it interrupted and reduced the income flow of many of these debtors. So, more loans defaulted, aggravating the USA depression, which aggravated the depression elsewhere.

One further aggravation stemmed from economists’ rigid defence of their dogma. The market must be allowed to heal itself, went the creed, and experts paraded no action as the best action. Business leaders generally believed this too, feeding another piece of dogma: that actions contrary to the views of market forces would decrease business confidence and so exacerbate existing problems.[331] Hence, little effort to ‘cure’ the Great Depression was made until it had been running for more than three years – by which stage, prices, output and money supply had all been slashed by up to a third, and USA unemployment had risen to about one person in four. In Galbraith’s words: “The rejection of both fiscal… and monetary policy amounted precisely to a rejection of all affirmative government economic policy. The economic advisers of the day had both the unanimity and the authority to force the leaders of both parties to disavow all the available steps to check deflation and depression. In its own way this was a marked achievement – a triumph of dogma over thought. The consequences were profound.”[332]

The influence of economic dogma (perhaps) aside, the causes of all depressions and recessions, of the business cycle itself, and of the various sources of its aggravation, arise ultimately from the pursuit of self-interest, capitalism’s first commandment. Competition for profits, dividends, interest, income, goods – real and imagined wealth in general – guarantees that some win and some lose. Nothing, not even government regulation and money-printing, can long compensate for the nature of a zero-sum game.

5.3 Regulating The Free Market

“If the market fails, so does the case against government intervention.” – John K.Galbraith[333]As mentioned, during the Great Depression, Keynes advised that because the market cannot regulate itself, the state should help by boosting demand when thought too low, and reducing it when too high, thus keeping the economy on the fine (often indiscernible) line between the depressed stagnation of insufficient consumption and the inflationary burn-out of over-spending. Of course, such a role for governments diverged markedly from that recommended by neoclassical theory – namely, running defence, law, prisons, and police; building and maintaining roads, lighthouses, and various public works; providing a minimal level of care for the poor and disadvantaged; and handling any other public goods for which exclusion of non-payers was not feasible. But according to Keynes, governments had a lot more to do than this.

Since Keynes, governments have attempted to keep the economic flow evenly churning over by using two main types of regulation of aggregate demand. ‘Fiscal’ (or ‘Keynesian’) regulation varies government revenue and expenditure, whereas ‘monetary’ regulation varies the amount of money and credit available to an economy, often via interest rates (both approaches are detailed in the next section).[334]

Fiscal policy determines the extent not only of taxation, but also of producer subsidies and grants (such as farmer support payments and business lunch allowances), welfare benefits, and all other state spending, such as for education, public transport, housing, and commercially unviable research and development (principally how nuclear energy, for example, was developed). Some governments also fiscally budget for running coal and/or electricity production, some telecommunications, a bank and airline or two, and other ‘nationalised’ (state-owned) industries and companies – although many fewer of these now remain after recent decades of widespread ‘privatisation’ ie. selling of government assets to private industry. (Once upon a time, in some nations, over half of all employed people worked directly or indirectly for the state.)

But while fiscal and monetary regulation have turned laissez-faire free markets into what are called ‘mixed economies’, unfortunately they don’t work optimally either.

The state can’t hope to make up for the pitfalls of competition any more than Stan Laurel could have hoped to have made up for Adolph Hitler. Apart from fiscal and monetary regulation often just not working (as the next section details), in a populous and complicated ever-changing world, governments may not even know how to identify what regulation should take place. Keynes might as well have suggested giving the job to Superman.

Governments have their own self-interest to pursue, in any case, and some measures thought necessary for an optimal mixed economy might have enough disadvantages (for some voters) to encourage governments not to implement them, for fear of later being voted out of office. For example, anti-inflation policies nearly always reduce employment and income, voter concerns obvious enough for even governments to recognise. Ultimately, because it must attempt the hopeless task of trying to please everyone in a game where winners must balance losers, the state always remains part of the market, and therefore cannot play the role of the market’s fuse-like optimiser. But if the would-be regulator forms part of the market, the market is not regulated – even after Keynes, it can only self-regulate.

In many nations, rather than acting as economic regulators, governments and their state employees have adopted roles more closely akin to those of monoligopolists, with close links to others. The phrase ‘lobby power’ says it all. Big Business pays some of its employees to keep governments informed about its desires and plans, and tries to persuade them to co-operate. And the state attempts the same in return. Indeed, because the success of a government depends greatly on the economy’s performance, which is determined largely by the performance of the economy’s biggest players, Big Business and Big Government have very strong mutual interests. Sometimes Big Business and Big Government can even act like friends: occasionally, business can help out governments via the media by prodigiously propagating prestigious praise, while the state bails business out of trouble with a big subsidy or tax concession or even a loan or grant (or it delays and/or minimises pollution or other taxes).

Big Business receives such privileges because some large monoligopolist corporations employ so many people that should they fail, not only would their employees suffer and the nation’s growth falter, but innumerable smaller firms they use during production would lose revenue: parts producers, transporters, advertisers, legal and scientific experts, banks, office furnishers, locksmiths for the weekly executive washroom ritual, people in miscellaneous service industries, and many others. Revenue lost by these small firms, in turn, would cause income to be lost by the firms they use, and a domino effect could ensue to affect an entire economy, wiping out business confidence. Consequently, while small players such as milk bars and bakeries are left to their L$D-fate, when large but ‘too-big-to-fail’ firms have visions of the final profit, they have a saviour to whom they can turn – with taxpayers who did not directly enjoy the earlier spoils of success paying for the avoidance of failure, usually with no repayments owing. As Galbraith put it, “there is first the speech on the eternal verities of free enterprise and then the case for the particular exception. Socialism in our time is not the achievement of socialists; modern socialism is the failed children of capitalism.”[335]

As a result, sometimes, distinguishing Big Government and Big Business is not easy. Consider the mutual masturbation of the military-industrial complex. In most countries, the military depend upon a few large-scale industries for their hi-tech weaponry, and these industries depend upon the military for business that would otherwise not exist. The consequent marriage has produced, no doubt, much deeply satisfying employment, income, and associated pleasures of consumption for both parties (as well as sufficient overkill to wipe out all life on the planet many times over – if that were possible). It has also made the task of government much easier: to keep the favour of the military (and so minimise any chance of a coup), to keep them well-armed, to maintain the profitability of the industries supplying them, and to avoid any loss of jobs in those and dependent industries, governments ‘only’ have to keep spending on defence the same or more each year. To reduce defence budgets (as was done briefly after the cold war ended) causes hardship all-round (although it may be required to avoid other hardships such as high taxes or big budget deficits).

So, although governments certainly play larger roles than they once did, economies nonetheless consist – and have always consisted – of a private (business) sector inextricably tied by mutual self-interest to a public (government) sector. Self-regulation.

But if the market fails to guarantee optimality – with or without perfect competition – and government intervention also fails, then what? Given the neoclassical tradition so far revealed, it should come as no surprise that the claims of Keynes have always been resisted by fervent laissez-faire enthusiasts. Many conservative economists – especially monetarists, supply-siders and other free marketers – continue to argue for a return to as free (meaning competitive) a market as possible, preferably without such ‘uncompetitive’ features as minimum (or even award) wages, and with much smaller, less intrusive government. ‘Nobel’ laureate Milton Friedman, for example, claimed that “government is today the major source of economic instability.”[336] (A less well-known writer called “[p]olitics… the exclusive reason why the economic situation has degenerated as far as it has.”[337]) In Friedman’s view, government fails because “bureaucrats spend someone else’s money on someone else. Only human kindness, not the much stronger and more dependable spur of self-interest, assure that they will spend the money in the way most beneficial to the recipients. Hence the wastefulness and ineffectiveness of the spending.”[338]

Certainly, governments often do seem ineffective and wasteful… inefficient… absurdly extravagant… short-sighted, corrupt, and incompetent… intrusive, insufferable, even imbecilic. And free market advocates can certainly find endless statistics to support this view.

As one example, Friedman pointed out that, in 1978, the USA government spent $90 billion on one hundred social security programs for the poor, enough money to have provided an average of $14,000 for every poor family in the country at the time. If the money had all reached the poor, they would not have been poor; but instead, poverty grew as most of the money was “siphoned off by administrative expenditures, supporting a massive bureaucracy at attractive pay scales.”[339] One other notable Friedman statistic claimed that the USA government’s Health, Education and Welfare department, “[b]y its own accounting, in one year… lost through fraud, abuse, and waste an amount of money that would have sufficed to build well over 100,000 houses costing more than $50,000 each.”[340]

Despite these examples, however, conservative belief that a smaller government corresponds to a more successful economy does not accord with the facts. For some time, many nations with as much or more state intervention and regulation than the USA competed more successfully – Japan, for example, and Germany, home of the saying, “as little government as possible, as much government as necessary”.

Of course, many factors other than the extent of state intervention affect economic performance. For instance, after the obliteration of World War 2, Japan and Germany were rebuilt with the newest technologies, which gave them something of an advantage over more archaically equipped nations like Britain and the USA. War treaties also prevented the ex-Axis powers from engaging in costly arms races and offensive defence. Other recent winners like Hong Kong and Singapore are very conveniently located on trade routes; many, including Thailand, South Korea and Taiwan, have mainly achieved their spoils at the cost of even greater than usual ecological destruction; and most, including the burgeoning India and China, have relied upon what could politely be called low wage rates or, impolitely, sweatshops. Yet all these economically successful nations have had interventionist governments. Culture, tradition and history do affect each nation’s capacity to accept and co-operate with economic leadership by the state (although once economic success is gained, state rule usually grows less acceptable, as best exemplified by South Korea), but rather than dwelling on the quantity of government intervention, the emphasis should surely be placed on its quality.

Because inefficiency varies from one government to another (just as it does from one business to another), suggesting that a nation need only reduce its government as much as possible in order to obtain the best possible outcome seems as naive as the ‘opposite’ suggestion that all politicians can be trusted. Furthermore, self-interest rather than “human kindness” might make more monetary profits, but as earlier sections showed, no reason exists as to why it should result in greater overall benefit. Government can be shrunk but the non-optimal inefficiencies and inherent instability of an imperfectly competitive free market would still exist: maximum profits would still be chased at the expense of unsatisfied needs.

Nevertheless, governments remain, and regulate they try…

5.4 Failed Remedies

“To end unemployment by increasing aggregate demand sufficiently to affect output in all sectors allows the monopoly sector to set off another inflation spiral. To end inflation by reducing aggregate demand sufficiently to affect monopoly prices causes catastrophic unemployment in the whole economy.” – Howard J.Sherman[341]Keynesian fiscal regulation requires governments to compensate for bothersome variations in aggregate demand by varying their taxing and/or spending habits. Inflation warrants higher taxes and/or lower government spending (perhaps a budget surplus), in order to leave people less income, and so compensate for the excess demand supposedly pushing up prices. On the other hand, in times of higher unemployment, such as recessions, the remedy is said to lie with reduced taxes and/or higher spending (often more than governments receive, usually arranged via increased budget deficits financed normally by borrowing – see section 4.3), in order to give people more income, and so compensate for inadequate demand.

Shortly before Keynes formalised these views in 1936, Adolph Hitler (a well-known eligible bachelor, Wagner fan, and believer in Jewish banker conspiracies) adopted a similar approach for dealing with Germany’s depression – though he did so not because of any great affinity for economics, but rather “as an ad hoc response to what seemed over-riding circumstance”.[342] Hitler’s government borrowed hugely via bond issues to run budget deficits that paid for vast public works programs which employed sufficient numbers to reduce German unemployment to minimal levels by 1935 (which increased tax revenue enough to pay off the bonds). But outside of Germany, none attempted Keynesian fiscal management so ruthlessly, and the depression dragged on – until World War 2 provided unarguably urgent reasons for spending, and Keynes’ heresy gradually became orthodoxy. Indeed, Galbraith claimed that: “The Great Depression did not, in fact, end. It was swept away by the second World War.”[343] Remarkably, under the influence of L$D, economies are often measured as ‘progressing’ when their depression gives way to the psychosis of war.

World War 2, in its own unique way, provided a matchless opportunity for the spending of money. Like chronic shoppers, governments spent to keep depression at bay. Likewise for subsequent hot and cold wars which prompted defence spending sprees often totalling, in the USA, a quarter or a third of all government expenditure. No wonder Sherman suggested that “only large-scale military spending brought the United States out of the great depression of the 1930s, and only large-scale military spending has kept the United States out of a major depression [since].”[344] Governments can spend in many ways, including on social welfare, unemployment benefits, subsidised health care and education, poverty relief, infrastructure, and much else, but it seems in none so easily as ‘defence’. Certainly, with a few exceptions such as business subsidies, and expenditures for roads (which suit big oil and car manufacturers), most potential forms of government spending – such as for housing – motivate objections from groups who consider their interests threatened, either by government competition in their own business fields, or by the redistribution of income implied. The military-industrial complex, though, lacks competition, and tends to do very well from fiscal policy.

Aside from increasing spending, governments can also fiscally deal with recessions by reducing taxes. But in times of extremely low demand, for either action (or both) to sufficiently stimulate an economy, the budget deficit and its corresponding debt-burden may need to grow dangerously high. Even if only regarded as dangerously high, this may lead to lowered currency values as foreign investors lose faith and flee the country – which may provoke a response of raised interest rates to attract them back, something likely to entrench a recession further.

However, according to supply-side economists, tax cuts not only pose a lesser risk than increased spending, they may also even reduce deficits rather than increase them. According to Gilder, “lower tax rates can so stimulate business and so shift income from shelters to taxable activity that lower rates bring in higher tax revenues”,[345] which allow governments to maintain spending without increasing their deficit or requiring any extra (potentially inflationary) money-printing. Furthermore, in the supply-side view, if governments have earlier set high taxes, tax cuts can so lower business costs as to even reduce inflation at the same time as they increase demand to overcome recession.

Adopting a supply-side stance in 1981, USA President Reagan introduced “a massive tax cut, mostly for affluent individuals and large corporations”.[346] The USA climbed out of recession with inflation kept at a few percent, but, contradicting Reagan’s avowed commitment to smaller government, federal spending increased, especially in defence – in real terms, by about fifty percent between 1980 and 1990.[347] Because tax revenue failed to increase proportionally, the budget deficit soared. Supply-siders, rather than admitting defeat, claimed the high deficit unimportant, and emphasised instead the stimulus it provided to work and invest: “In an expanding economy money available now is many times more valuable than money paid later in interest on payments diffused through the economy in higher prices… Only in a static, uncreative economy, does it pay to pay as you go.”[348] In other words (as goes the theory for money-printing), growth can compensate for increased debt. And of course, it can – if enough of it occurs, but this of course remains a gamble. Likewise, supply-siders’ rosy hope of an inflation-free increase to demand via tax cuts cannot be guaranteed: lowering of business costs because of reduced taxes can be more than offset by demand-pull rises in bottleneck sectors, and/or by monoligopoly and union power inflation (see section 4.5).

Just as the Keynesian remedy for recession, and its supply-side variant, have their considerable problems, so does the standard Keynesian prescription for controlling inflation. Raising taxes and/or cutting government spending can stabilise or even reduce prices in areas of the economy where players have no market control, but downwardly-rigid price-setting unions and monoligopolies react to decreased demand by reducing employment and lowering production. If governments apply anti-inflation fiscal policy long and hard enough, cost-push forces can be beaten, but only at the expense of high unemployment and recession or depression. Like ending indigestion by disembowelment. Even so, no fall in demand could stop L$D-competition from requiring the invention of wants and the creation of counter-productive ‘work’ – these causes of inflation (see section 4.5) cannot be dealt with by fiscal policy alone, even when extreme. Nor can fiscal policy deal with simultaneous inflation and recession, as has happened in recent decades, because inflation has to be met with reduced government spending whereas recession requires a contradictory increase to spending. Nor can it adequately contend with multinationals. Possibly more than half of all foreign trade transactions occur between companies that have the same multinational owners;[349] so, taxes tend to be paid in nations with the lowest tax rates, and local fiscal policy tends to be circumvented.

Not only can’t fiscal policy cure modern inflation, it can rarely even be attempted. If vested interests make it difficult to spend more, then they make it even harder to spend less. Government spending cuts and tax hikes tend to be seen as threats against ingrained habits of consumption and accustomed levels of affluence. In a downwardly-price-rigid economy, such measures invariably provoke great resistance, including electoral backlash. They may also have effects opposite to those intended: according to supply-siders, raising taxes, for high income earners especially, can often decrease government revenue rather than increase it – by inspiring people (who can) to use their money in non-taxable and usually unproductive ways. In an environment of perpetual want-creation, enforced thrift seems a gloomy and unenforceable contradiction. Of course, some taxes do get raised and some government spending does get cut, but almost never in defence, and nearly always in areas for which resistance can be least well organised, such as welfare. In Galbraith’s words, “the weakest and the poorest,… more than incidentally, are the least articulate. Military expenditures, needed or otherwise, are defended by strong corporations, formidable generals, a big bureaucracy. So they are never imagined to be subject to reduction for reasons of fiscal policy.”[350]

So much for Keynesian fiscal policy. It worked for a while, when hot and cold wars kept the spending machine going, and while the after-effects of the Great Depression left employment rather than wage rises the highest priority. It also worked, at least in the short-term, when the stark imperatives of the Great Recession caused it to be dragged out of the ‘no longer fashionable’ box and, despite vociferous disapproval from conservatives, applied with abandon – however, the government and central bank debts accrued in the process, and later by all but identical responses to the COVID Recession, seem likely to prove that success short-lived, the final result probably fated to accord with the conclusion that, since the 1960s, fiscal policy has mostly proved “too painful to use”.[351]

By the 1970s, the helplessness of Keynesian regulation in the face of high inflation had assisted the resurrection of the monetarist approach of ‘controlling’ the money supply. A fuller explanation of monetarist theory and the difficulties of applying it to a real economy is provided in the appendix, but, in essence, its advocates argue to increase money growth in recessions, and decrease it during times of inflation. This sounds simple in theory, but does not prove so in practice. For one thing, as the chief advocate, Milton Friedman, himself recognised, a lot can happen in the roughly two years it takes for monetarist regulation to ‘work’, enough to alter conditions sufficiently to thwart the expected results, or render them detrimental.

Especially when dealing with inflation, a slight misjudgement of the unavoidable “painful side effects”[352] caused by tighter money – heightened unemployment and reduced trade – can easily turn into a grave error two years later. This was demonstrated more than amply in Australia when interest-rate-led monetarism, applied with unbending loyalty (if not sadism) during 1988 and 1989, pushed home mortgage interest rates from 11.5 percent to 17.5 percent (business rates even higher), but was accompanied by inflation slowly and erratically continuing to climb from about seven percent in early 1988 to 8.6 percent in early 1990. Meanwhile, unemployment stayed roughly constant at about six percent. Then, true to the two-year time-lag claimed by monetarists, the policy bit (like a fundamentalist ferret). By the middle of 1993, inflation had fallen to under two percent, and interest rates to less than seven percent. But economic nirvana was not attained: in what the Treasurer planned at the time as a ‘soft landing’ but which he later reluctantly called “the recession Australia had to have”, unemployment almost doubled to over eleven percent (forty percent for teenagers), and real wages fell. So, monetary policy traded everyone’s inflation for nearly everyone’s loss of income. Yet while most suffer because of anti-inflation monetary policy, some do so more than others…

Slowed money growth means reduced lending and/or higher interest rates. While Friedman and other monetarists have criticised most governments since the 1970s for trying to slow money growth using mostly just higher interest rates, Galbraith remarked: “If there were a perfect and possible design wholly to… [monetarist] specifications that worked and was reasonably painless, it would, of course, have been used before now… But there has been plenty of practical proof both of the unworkability and of the pain.”[353] As regards unworkability: whatever the method used to slow money growth, banks that exceed their reserve requirements can lend their excess. Monoligopolies too can use their profits for investment, or turn to subsidiaries or foreign banks for cheaper loans. They need rely on local banks only as a last resort, one made easy by their wealth-backed credit-worthiness and their ability to pass onto customers the cost of whatever interest rate is charged. But while monetary policy to monoligopolies compares to water off a duck’s back, none of their skills of evasion reside with firms who lack market control, who must compete. In Galbraith’s words, “the farmer, the small tradesman who needs money to carry his inventories and, above all, firms in industries like housing which operate on borrowed money and depend on customers who borrow money are highly vulnerable to monetary policy. So… it works… by creating unemployment, by exempting the big and strong corporations and by putting the squeeze on the small and the weak.”[354] Hence, monetarist anti-inflation policy (like the fiscal counterpart) cannot evade what inflation itself produces: suffering for the weakest.

Monetary policy also acts less than perfectly against recession and unemployment. Making money more freely available by increasing lending and/or lowering interest rates can raise demand, but interest rates can only go so low, perhaps not enough in a depression. The Great Recession, for instance, saw the central banks of the USA and Japan quickly lower their bank rates to zero percent, yet both economies grew at a snail pace for years after. Just as higher interest rates do not always thwart borrowers confident of their ‘sure thing’, lower rates do not always tempt those lacking theirs. As Sherman put it: “You can lead a businessman to the river of loans, but you cannot force him to drink… In short, monetary policies may have some effect in minor recessions, but when pessimistic expectations become general in a depression, monetary policy may be able to do little or nothing to expand the volume of spending.”[355]

Sometimes, increased money growth does successfully lower unemployment; but in doing so, it adds its own pressures to inflationary tendencies. Indeed, ignoring dubious supply-side exceptions, monetary and fiscal policy alike can only fight unemployment or inflation, not both – and only by trading one for the other. Fiscally or monetarily increasing demand aggravates modern economies’ innate inflationary tendencies; decreasing it reduces the need for production and, in a downwardly-price-rigid economy, employment.

Yet because demand consists not just of money or income with which to spend, but also the desire to spend, fiscal and monetary regulation – when they can be applied – affect demand only approximately. Like ‘money supply’, ‘aggregate demand’ has no easily manipulable counterpart in the real world. Monetarily altering the volume of the economic flow, or fiscally changing the distribution of that portion of it involving government, cannot guarantee a more efficient or consistently expanding overall movement because extra income, however made available, can only encourage spending and investing if enough people know of things they regard as worth buying and investing in. Whatever the amount and distribution of money, people still need to know how to use it profitably, and this knowledge cannot be regulated to grow at the ‘right’ pace. Growth requires ideas (even ill-conceived ideas) of how to grow, else the loans ready to fund the conversion of ideas into jobs, products and sales lay dormant. But ideas can’t be guaranteed to turn up continuously as needed, least of all ideas for new products, new reasons for parting the fool and his/her money.

Ultimately, attempts to regulate economies require a series of simultaneous but often contradictory juggling acts of interdependent yet sometimes countervailing forces. A growth-inducing boost to consumption, for example, often means decreased savings, which tends to reduce investment, which lowers growth. Increased investment often stimulates not only growth but also inflationary pressures, which tend to reduce consumption and (consequently) growth. Rising productivity boosts profits which assists growth but eradicates jobs which retards growth. Higher interest rates motivate lending to riskier borrowers but increase the likelihood of those borrowers defaulting. Reducing government spending to pay off debt can lower growth enough to decrease government revenue, making it harder to pay off debt (the current conundrum for many overly indebted nations).

The juggling acts also require superhuman precision. Not simply growth, but growth at just the right pace: too much yields inflation, too little and jobs are not created quickly enough to compensate for those lost to rising productivity or cheaper competitors. Unemployment must be kept low, but not so low it encourages higher wage demands, which can increase inflation, which can prompt even higher wage demands to compensate, which can prompt even higher inflation, and so on until the economy disappears up its hyper-inflated assets. Inflation too must be kept low, but not so low that it deters investment and growth and leads to stagnation or deflation. Interest rates can’t be set too high or they discourage borrowing and risk putting the economy into a recession “we had to have”, yet they can’t be set so low either that they deter saving and foreign investment. Property, bond and equity markets should rise but not so quickly they risk turning into bubbles. National floating currency exchange rates should be high enough to afford imports but not so high they discourage exports. And so on… and on…

Even population growth, like all the other juggling acts, has to be Goldilocks perfect, with just the right amount of breeding (something beyond the control of even our über monopoly economic system). Capitalism can’t handle too many old people: it needs enough working age people to pay enough taxes to support retirees through pensions and health funding – if the aged proportion gets too high, then, in order to ensure all the work that’s needed gets done, taxes and/or wages might need to rise, which could upset all the other juggling acts.

Never mind, just another ‘market failure’ – to be fixed, eventually, by the market via more juggling acts. Keep working. Keep shopping. And do ignore all the clowns juggling other clowns juggling their economic balls.

Ultimately, the bitter policy pills regarded by Keynesians and monetarists as, in the long run, worth popping, cannot cure economic ills because the sicknesses, though worsened by internal imbalances, stem from fundamental institutionalised attitudes and habits – from the L$D-competitive pursuit of profit and self-interest.

In the end, it doesn’t matter how much devotion and effort governments and businesses put into keeping the treadmill ever rolling along, how many new jobs are contrived, how frantic the spending and chasing of fluctuating phantom values – none of the orthodox impossible Goldilocks juggling acts can stabilise L$D-competition, because they leave unchanged the game rules and motivations which create instability and foster inefficiency and social and ecological decay. As Steve Keen pointed out: “Reform, of course, cannot make capitalism stable”.[356]

Government regulation of L$D-competition must fail: the unfathomable complexity and unpredictability of so many different people in so many different nations, the constant shifting of alliances to suit self-interest, the often blistering march of technical and scientific innovation, and the various time lags between event, perception, cognisance, and response, subvert the economic authority of even the most peerless trustworthy governments, prevent them gaining sustained or pervasive control, and defeat their best and worst efforts. Ultimately, for all their prognostications and pronouncements, regardless of their pomp and ceremony, and in spite of their real and imagined power, governments act more as belated commentators of past events than manipulators and shapers of the future.

5.5 Losing The Game

“To convert the business man into the profiteer is to strike a blow at capitalism, because it destroys the psychological equilibrium which permits the perpetuance of unequal rewards. The economic doctrine of normal profits, vaguely apprehended by every one, is a necessary condition for the justification of capitalism.” – John Maynard Keynes[357]Clearly, the myth of economic ‘equilibrium’ does not occur, nor can L$D-competition produce optimal universal prosperity. Instead, because the inclusion of profit in prices ensures that someone has to lose – somewhere, sometime or another – regardless of their efficiency, the game rules, as well as the short-term measures designed to keep the system going, sub-optimally guarantee the ever more long-term prices of instability, towering debt, resource misallocation, and social and ecological decay.

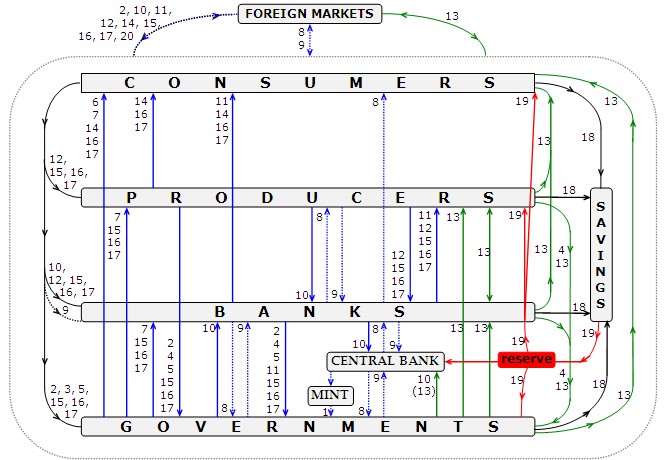

Similarly, Figure 2’s neat circular flow between producers and consumers doesn’t occur. The less simple real world has more in common with Figure 5 below (although this still simplifies). Imagine it as groups of many pumps each siphoning liquidity to and from the other, interdependently through hoses, recycling money over and over. The real wealth and other items exchanged for money are denoted by numbers attached to each particular flow, as per the diagram’s legend. The dotted lines represent initial provision of credit, which turn solid when circulated further into the flow, and its repayments. Don’t ask where the flow starts or ends in such an arrangement – in this accident of history, cause and effect intermingle.

____ |

Production |

_____ |

Consumption |

____ |

Profit redistribution |

____ |

Savings |

........ |

Credit & repayments |

1 government bonds (sold to central bank) |

11 deposit interest |

2 government bonds (sold other than to central bank) |

12 securities |

3 income tax |

13 share dividends, bond interest & maturity payments |

4 company taxes |

14 labour |

5 other government charges (incl. bank account taxes) |

15 goods & services |

6 government welfare |

16 assets (re-sales of property, durable goods, etc.) |

7 government subsidies/grants |

17 rent |

8 credit |

18 deposits to saving |

9 credit repayments |

19 withdrawals from savings (via banks) |

10 credit interest |

20 currency speculation |

Each group holds money & trades it for 2,9,10,12,15,16,17. Consumers also trade for 14, and banks for 11.

Plus, much genuine but unpaid work exists (eg. housework), & many unrecorded black market transactions.

Figure 5: The Economic Flow – Exchanging Money

Viewed in this way, capitalism consists of a perpetual contest between its interconnected players over the contents of a complex and turbulent, yet coagulated, eddy-filled flow of liquidity – the aim, to suck as much as possible, and simultaneously expel a bit less – the result invariably leaving some fully immersed if not drowning but others gasping.

It’s all about money, topped up in spurts as banks find borrowers, and central banks print it. Pass the parcel: pull it in, but pump it out quickly to keep it all flowing. Try, though, to retain some liquid, to suck in more than is given out, to profit – even though doing so creates whirlpools and vortices that thin the rest of the flow…

The vortex-ridden flow cannot stabilise because, although some pumps manage to profit, others (as section 1.5 explained) must lose. Finding themselves immersed in a mere trickle, or sucking air, pumps can delay loss by slowing down (cutting production), borrowing liquidity from others (going into debt), or partially liquidating (selling assets), but eventually some are caught in the undertow of others and lose all their liquidity to them. Gasping at thin air, the pumps seize, the flow diverts round them, and they are left high and dry, their losses also interrupting the flow for others.

Amid the turbulence, the flow dragged away from pumps to make profits for others initially congregates in the sometimes stagnant backwaters of the savings pool. If profits and savings are not soon recycled back to the flow, either as consumption or investment (new or enhanced pumps), or to holders of securities, the flow stays diluted, and the economy runs the risk of being sucked dry. Savings that recirculate as credit top up a diluted flow, but they require counterflows back to savings of repayment plus interest. Similarly, central banks top up the flow with freshly minted money but demand more tax revenue back. So, although dependent on borrowers maintaining their vortices, lenders, by pursuing profit, create their own whirlpools. But not all vortices can be sustained – some have to fail.

At times, an excess of liquidity seeps in, recirculating from reinvested profits, credit, exports, and money-printing – the economy booms. But as an economy grows, debt accumulates, and business and wealth concentration increases as losers acquire smaller slices of the economic cake, and winners, bigger shares – all of which eventually results in so many interdependent losses, so many failed pumps, that the economic cake curdles.

When an economy busts, its savings, credit repayments, and imports drain away the liquid seeping in, and with winners’ profits dormant due to insufficient ideas about how to compound their winnings, hordes are left gasping. Usually, the system coughs and splutters until liquidations unclog the flow, government and central bank injections of liquidity flood it, profits recirculate, and things begin to boom again. But because profits then grow again, the flow sooner or later starts to coagulate and ebb again.

Sometimes, if liquidity is highly concentrated, debt excessive, investments clustered in speculative dreamlands, and/or pumps more interlinked and/or struggling with the speed or bulk of an inflationary flow, the trouble of one spreads more quickly to others, and more suck air. When bursting speculative bubbles evaporate much liquidity, and/or when many pumps horde theirs and keep it away from the economic flow, the diluted current can lose momentum and collapse to a depressed trickle. Like a game of musical chairs, most lose. Then, the survivors pick up the pieces, eventually get some new ideas for making stronger, better connected pumps, print new tickets of liquidity to fill their hoses, and start sucking again.

Modern conditions provide greater difficulties than ever before, because vaster numbers of game-players complicate economic activity; because the world economy grows ever more singular and interdependent, providing each player with more and better informed competitors, and increased risk; because financial markets fabricate increasingly dominant, turbulent and interlinked yet unproductive flows via their concoction of ever more dizzyingly complex and inadequately understood bets and gambles about which way other flows go; because escalating debt makes for a larger amount of unrealised profits which form a particularly destabilising and sickly icing on the economic cake; because cumulative ecological abuse has bequeathed a more fragile, less cheaply exploitable environment; and because technology’s overcoming of scarcity makes it ever harder to devise truly useful ideas for profit-maximising investment and associated employment. With more swirling liquidity, more vortices sucking and gushing, comes an ever more unstable, inefficient and dangerous game. Hence, the last quarter of the twentieth century involved almost one hundred economic crises, “more frequent (and deeper)” than previously.[358]

Too dynamic for equilibrium or stability, too complex and large to control or guide or regulate, the flow has far too much interdependent activity for all the countervailing dynamics and conflicting attempts to influence it to ever fluke a perfect balance.

In the end, the economic doctrine that an optimal result follows from leaving everyone to look after themselves, makes sense only if attempting doublethink; otherwise, with or without government ‘intervention’, self-regulation seems transparent nonsense. Put another way: however much pump-priming goes on, capitalism still sucks.

Pursuit of self-interest defines capitalism, but also condemns it. To continue to compete for self-interest, and profits, can only aggravate most problems because they originate from just such competition. Modern business civilisation has a systemic problem, and no amount of tinkering or changing window dressing will suffice. The fundamentals need to be changed…

Chapter 4 Chapter 4 |

Part 2 |