Chapter 4

Money & Wealth

“There have been so many changes and they come so fast and nobody really understands the international monetary system. I believe the long run stability of the system is in question.” – M.Johannes Witteveen[227]While the game of competition uses prices as the scores, money acts as a symbol of wealth meant to facilitate both the scoring and the game. Too often though, money takes over the game, becomes its end rather than its means. LSD turns into L$D, reducing prices to numbers that mean next to nothing – mean only what we perceive or choose to ascribe to them.

This chapter examines the use and abuse of money, beginning with a brief historical overview of the many forms it has taken since its inception, which makes obvious how, to successfully function, money requires widespread agreement or belief. Too often, though, that belief confuses money with wealth, which further corrupts the market’s flawed price signals, encouraging even less optimal results including the frittering away of energies on money-making but wealth-destroying goals. (Section 4.1)

Confusing money with wealth also results in the charging of interest for borrowing money. Ownership allows and competition compels interest, but, as a consequence, lending is restricted to ventures expected to make profits, not efforts that satisfy more pressing needs, such as homes for the homeless. (4.2)

Confused beliefs also lead to modern financial exchange that can look like sleight-of-hand or, particularly regarding banks (4.3) and speculative markets (4.4), like delusion. With no more than the flourish of a pen, loaves-and-fishes banking systems lend money many times greater in amount than the savings left by depositors. Reserve Banks create money on receipt of nothing more tangible than government-completed forms. Currencies fluctuate, constantly shifting values based on perceptions, incessantly being bet upon, for and against. Creative accountancy manipulates ledgers to transform a reality of bankruptcy into a pretence of profit. Fickle manic depressive (sometimes paranoid) markets for bonds, stocks, derivatives, shorts, mortgage-based bundles, collateralized debt obligations, credit swaps, and various other too-clever-by-half exercises in self-deception – glorified IOUs and bets upon gambles – conjure up cash flows with almost as much ease as they lose them (the traders’ assumptions, biases and perceptions now enshrined in automated computer trading programs).

The constant turmoil of our confused monetary beliefs – the endlessly shifting values of interest rates, debt levels, currencies, stocks, bonds, and derived fabrications – also lead naturally to frequent and often undesirable changes to the prices assigned to real wealth, their inherent inaccuracies and flawed functioning as market signals corrupted further by inflation. (4.5)

4.1 Can You Believe It?

“You have to decide whether you make money or make sense, because the two are mutually exclusive.” – Buckminster Fuller[228]Money sounds absurd, unless one’s ears have been tuned just right…

The handing over of a few pieces of paper or coins, to receive in return the objects or services of one’s desires, would seem an act of magic if it did not comprise such an ingrained habit and prime feature of our consensus tunnel-reality. Of course, such magic is meant to prevent time and energy from being eaten away in barter. However, this convenience comes with a price that, over time, has rendered money’s magic at least as much black as white.

Since its invention millennia ago, money has taken diverse forms – including cattle, beads, shells, whale teeth, tobacco, stone disks, cigarettes, and liquor[229] – and come in many different national brands (currencies): the USA has dollars, England pounds, Germany marks, Iran rials, Laos kips. (Money also has many alternate names, including cash, dough, bread, bills, greenbacks, moulah, wampum, scratch…) Today, most money exists as book-keeping entries and as bits of information in computers, but quite a lot still takes the form of metal coins and paper. (…dosh…)

To supersede barter, money necessarily functions in two ways: as a ‘medium of exchange’ – something that can be accepted in return for goods and services – and as an ‘asset’ – something that can retain its value between its acquisition and exchange. (…palm oil…) The dual functioning of money has been most commonly attempted using metal, especially silver and gold. Early metal money dates back four thousand years, but not until the seventh century BC did a state issue standardised coins in any quantity. Probably first minted in ancient Greece, early coins, shaped like beans, consisted of both gold and silver, and were stamped to certify their weight and/or purity.

Though rarely the case now, a coin’s content once determined its ‘value’. For instance, between roughly 600 BC and 350 BC, the Athenian drachma contained about 67 grains of fine silver,[230] so that exchanging a drachma equated to handing over a definite quantity of precious metal. Because the ‘value’ of goods in terms of drachmas was thus directly and stably related to the ‘value’ of goods in terms of silver (which in turn was ‘determined’ by LSD), the drachma’s content enabled it to be treated as an asset of known value and, hence, also as a medium of exchange. Because of its content, the drachma had what is called a silver ‘standard’. But, like all currencies, the drachma eventually lost its standard, because of deliberate ‘debasement’ of the coinage. (…loot…)

For most of money’s history, people of sufficient inventiveness have found ways to manipulate it to suit their profit-maximising purposes. The oldest recipe for such financial ‘success’ consisted of removing some of the precious metals from coins (sometimes replacing them with less valuable materials) and selling the precious metals for more coins – to extract more metals from – to sell for more coins – to repeat over and over until satisfied (if ever). But when people found out that their coins had been debased in this way (or even when they only thought they had), they stopped trusting in the ‘value’ of their money – in its claim as an asset – preferring instead to trust precious metals or other items regarded as valuable and likely to remain so. Deprived of their official content, debased coins also performed less well as an exchange medium: people happily exchanged them for goods, but few people wanted them in return for goods – unless offered more than usual amounts, which meant generally rising prices or ‘inflation’. Not until the late seventeenth century, when coins began to be made with serrations around their circumferences (‘milled’), so that debased coins could be more easily detected, was the practice discouraged. Since then, however, various other profit-maximising practices have been pursued which have had adverse effects on money standards.

Prior to the twentieth century, many currencies were simultaneously defined as worth so much gold and so much silver, but such bimetallic standards did not last for long. (…spondulics…) At the end of the eighteenth century, for instance, after the USA dollar had been defined as worth a specific amount of gold, and fifteen times as much silver, an influx of silver caused the market to treat gold as worth more than fifteen times as much silver. For anyone then in possession of gold, profit-maximisation was achieved not by selling it to the government mint for them to use in coins but rather by selling it in the market, buying more than fifteen times as much silver with the proceeds, and then selling that to the mint. Consequently, the silver content of coins increased, and the metal overvalued by the official bimetallic definition became the effective standard. Years later, the dollar was redefined as worth sixteen times as much silver as gold, “which overvalued gold, so gold became the standard.”[231] These examples demonstrate Gresham’s law: readily exchanged (‘bad’) money drives out more trusted (‘good’) money, by causing it to be retained as an asset and so cease to function as an exchange medium.

A single gold standard – despite its reputation as the traditional standard, and despite its reign in Britain since 1717 – did not proliferate until late in the nineteenth century, after vast gold discoveries in California, Australia, and (later) South Africa had caused the LSD-price of gold in terms of silver to decline. By early in the twentieth century, most of the world had adopted a gold standard; this made conversion of one currency into another quite simple. For example, as Milton Friedman explained, at the time a USA “dollar… was defined as 23.22 grains of pure gold… A British pound sterling was defined as 113.00 grains of pure gold… Accordingly, one British pound equalled 4.8665 U.S. dollars (113.00/23.22) at the official parity. The actual exchange rate could deviate from this only by an amount that corresponded to the cost of shipping gold.”[232] (If exchange rates had deviated further, buying and shipping gold to settle a foreign debt would have cost less than exchanging local for foreign currency.) But the gold standard all but ended with World War 1, the emphasis since being placed on paper money.

Paper money was first used in a form called ‘fiduciary’: especially from the seventeenth century, paper notes were issued as the equivalent of IOUs, representing for the recipient a claim on, and for the issuer a promise to pay, a corresponding amount of the money’s metal standard (likewise, coins began to be made of only cheap metals like copper, tin, brass, and/or steel). Such an approach, however, tended to result in fiduciary money being issued in amounts which promised repayment of more precious metals than actually existed. (…gravy…) It didn’t matter as long as people kept the money and didn’t all try to swap it for the metal standard. But as over-issues became recognised, people lost faith in the money and did try to swap it, or else demanded a greater quantity of it in lieu of its perceived impoverished quality (just as occurred after coin debasement). Galbraith noted a few of the more distinctive historical examples of over-issued fiduciary money: “the paper money of the American colonies before the Revolution, the assignats that helped finance the French Revolution, the Continental notes that paid Washington’s armies and the Greenbacks of the American Civil War were all issued by governments on their own. And when the volume outstanding could no longer be sustained by the state from any available metal, conversion of the notes back into hard coin would be suspended.”[233]

Money that lacks convertibility into metal is called ‘fiat’ money. But dropping the metal convertibility of a fiduciary currency, and so making it fiat, has usually been done only in the extreme need prompted by war. Even the most reliable fiduciary money of all – British sterling, whose pounds, shillings and pence had stable values for almost two centuries – could not avoid twice being made inconvertible, in order to pay for fighting Napoleon and World War 1. In both instances, inflation followed as people found it difficult to believe in money not backed by metal. Between Napoleon and World War 1, however, British sterling acted as what a modern writer with the pen-name of ‘Adam Smith’ called the world’s ‘key currency’ – the money other nations trusted most and measured theirs against. (…lolly…) During its hey-day, people of many nations even keenly exchanged their own less reliable currencies for sterling, which gave Britain enough foreign money to help finance the building of its world empire. But like the British Empire, fiduciary sterling began to pass into history upon the outset of the First World War.

After suspending gold convertibility during the war, Britain reinstated it in 1925 at the pre-war standard. With higher prices, as a result largely of war-time inflation, this overvalued the pound, so exporters to Britain preferred payments to be made in gold. Britain increased interest rates to attract foreign money, which could be traded instead of gold, but this helped little – as did most else – and by the time the Great Depression began, though most of the world had also returned to a gold standard, sterling’s reign had ended. In 1931, sterling’s gold convertibility was again abolished, and the world was left without a key currency. Considerable chaos ensued: international exchange rates were no longer fixed and each country tried to use the situation to their own advantage. But when World War 2 tipped civilisation out of the frying pan and into the fire, the USA dollar took over the role of the world’s key currency. USA citizens could not convert dollars to gold, but central banks (see section 4.3) of foreign nations could – at the rate of 1/35th an ounce of gold per dollar. In 1944, forty-four nations fixed their currencies in terms of dollars (more nations soon followed), and with enough dollars “to finance the world’s trade”,[234] and in the absence of any alternative key currency, the international monetary system returned to fixed exchange rates.

But just as everyone wanted sterling last century, after World War 2 everyone wanted dollars. (…smackers…) The currency travelled everywhere, paying for the rebuilding of much of Europe, and then for the products it made, even for transactions denominated in dollars but not involving USA citizens or businesses. Yet while some dollars came back to the USA to buy its goods, by the 1960s more had piled up abroad: by purchasing more from other economies than they did of it, the USA had developed a balance of payments deficit. The Vietnam War, paid not out of taxes but by printing money (see section 4.3), exacerbated the problem. And by then, resurgent European economies were making products in many cases preferable to those of the USA, so they began to trade their dollars, in increasingly large amounts, for other gradually more desired currencies (especially Swiss francs, German marks, and Japanese yen). Thus, in only a quarter of a century, the key currency had lost favour.

From the late 1960s, dollars piled up in European and other central banks – which naturally chose to send the excess back to the USA, in exchange for gold (or, as section 4.3 explains, for government bonds). But the USA was not going to give its gold to foreigners in exchange for travel-worn greenbacks for long. “In August 1971 the United States Treasury stopped selling gold for dollars altogether. The potential claims on the gold were too great.”[235]

Since then, the world has not had a key currency (although, because of the sheer size of the USA’s economy, its dollars have nevertheless continued as usually the most dominant currency). Rather, as had been briefly and disastrously attempted during the Great Depression, fixed exchange rates between national currencies have been abandoned, and exchange rates vary from transaction to transaction, as determined by the buyers and sellers involved, and subject only to their own appraisal (occasionally modified by central banks, as section 4.4 explains). The present international monetary system thus consists of national fiat currencies mediated by ‘floating’ exchange rates. It has not proved stable, either.

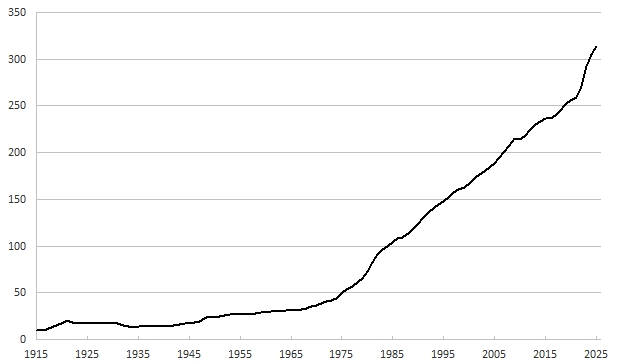

Since the 1970s, the ‘floating world’ has seen seething tidal waves of economic instability batter national prestige and performance. Indeed, without a bedrock on which to fasten our economic machinery, without a clear standard to measure the ‘value’ of money, it often seems we are drowning more than floating. In particular, prices have soared: a USA dollar that bought 1/35th of an ounce of gold from 1933 to 1971 could buy less than one-tenth of that amount two decades later, and by 2025, little more than one-hundredth. Conservatives often suggest beating a retreat to a gold standard, but the world’s central banks own too little gold for it to serve as a standard for the amount of money needed to maintain current levels of world trade (unless most currencies are redefined, contrary to LSD, as worth a very tiny fraction of an ounce of gold). Most of our current monetary problems, however, stem from something even more fundamental than the absence of a standard.

Money functions as intended only if most people using it accept it as what it is said to ‘be’: money. (…lettuce…) The logic seems circular, but without it money could not exist. Money ‘is’, in effect, whatever we believe it to ‘be’. Hence, with sufficient belief, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), an intergovernmental organization that oversees the global financial system and functions more or less as an international ‘bank’, could create its own currency in the early 1970s – the Special Drawing Right (SDR) – “by a stroke of the pen, by creating a new account and a new unit of account… not backed by gold or any other national currency… It derives its strength from the fact that the members of the I.M.F. are willing to accept it and use it as a means of payment between central banks in exchange for existing currencies.”[236]

As long as people are willing to accept a currency, the spell of belief holds and money magic works; but when the spell wears off, people start to treat inherently worthless metal coins and paper notes as inherently worthless. The spell wears off and people lose faith whenever coins are debased or paper is over-issued, or when money loses convertibility into a ‘real’ asset or erodes in value under high inflation or changes in any essential way from what we know and believe. Hence, floating exchange rates, which guarantee change (especially when adopted after centuries of fixed metal-backed rates) only ensure less belief and less convincing money magic.

Those who call for a return to a gold standard see it as able to renew belief (as it did in 1944). Yet gold is not the final repository of value. Like the metal-base of any fiduciary money, and like the money itself, gold can only be traded for things genuinely valuable (meaning useful) such as a meal or a shirt or a house – and only if people agree to trade it, which requires a common basis for exchange. So, whether fiduciary or fiat, metal or paper, precious or base, money can only be traded for goods if there exists a common acceptance of an utterly artificial definition of the money’s ‘value’. Money thus constitutes a not always maintainable “social convention”[237] or agreement, and its metal backing or lack, an arbitrary choice which, at best, may encourage the stability of belief necessary to maintain the social agreement. Ultimately, money depends not only on the backing of real wealth – including the environment and human imagination, from which all wealth ultimately derives – but on a society capable of agreement and of performing the work necessary to create the real wealth.

However, the convention of money tends to fail not just because of weakened beliefs, but also because of confused beliefs. (…shekels…) Whatever the particular form employed, people often confuse money with wealth – even though our social agreement, when maintainable, allows money merely to represent wealth. Money is not wealth, only its symbol. Wealth can be defined as physical objects or services which benefit humanity (John Ruskin likewise defined ‘illth’ as objects or services detrimental to humanity, such as weapons). But money merely represents the market LSD-valuation of the real wealth.[238] Robert Anton Wilson put it neatly: “Money is neither wealth nor illth but merely tickets for the transfer of wealth or illth.”[239]

Confusing the map of money with the territory of wealth, though, constitutes the norm. And the normal confusion motivates a pursuit of monetary profits which not only damages real wealth like forests, rivers and air, but also emphasises money’s asset quality so much as to inevitably weaken its capacity to function as an exchange medium. And so, we play not market competition, and definitely not perfect competition, not even LSD-competition, but L$D-competition, a game where players aim not to increase real wealth but to redirect and concentrate onto themselves the fluctuating wealth-symbols of the economic flow, by convincing others to part with their money for any reason that can be accepted. Such a game further corrupts the market’s flawed signals…

4.2 Vested Interest

“The trouble with paper money is that it rewards the minority that can manipulate money and makes fools of the generation that has worked and saved.” – ‘Adam Smith’[240]The creation of real wealth requires effort – directly as labour, indirectly as provision of tools, equipment, and know-how. Under L$D-competition, effort requires payment – even before the effort can produce consumable goods that can be sold at prices that might cover the monetary costs of the effort. Over the centuries, as the scale of production has increased, borrowing money to pay people to help create new wealth has grown more and more necessary. A very advantageous situation has thus developed for those with an excess of money available to lend – and of course, in a system based on the pursuit of self-interest, they exact a price for their lending, a price aptly called ‘interest’.

Money-lenders are particularly advantaged by the compounding of interest. If you borrow $100 at an interest rate of ten percent a week, then in a week’s time you could fully repay the loan with $110 ($100 of ‘principal’ plus $10 interest). But if you don’t pay next week, then a week later you’d owe not just $110, but an extra ten percent of that – a total of $121. Every week that the debt is foregone, you’d be penalised ten percent of the total amount owed the week before. After a year of no repayments you’d owe more than $14,000. (…oof…)

Partly because of its compounding nature, interest was condemned for most of recorded history as extortion. But as the scale of production increased in the last few centuries, opinions changed. In Galbraith’s words, interest became “reputable” when it “was redefined as a payment for productive capital – when it became compellingly evident that the one who borrowed money made money out of doing so and should, in all justice, share some of the return with the original lender”.[241] However, the lender’s return is generally not provided by the borrower but ultimately by the purchaser of goods produced by the borrower: producers who borrow can only have successful businesses if they add their costs of borrowing to the desired level of profit, and set LSD-prices to cover both. By adding a cost ultimately paid by consumers, interest turns LSD-prices into L$D-prices.

Of course, economics textbooks defend interest as a “natural cost” of borrowing money. They do so by treating money and credit (loaned money) as subject to supply and demand, which enables schedules of interest versus “quantity of credit” to be drawn. Yet this approach does not justify why a mere symbol of wealth should be ruled by LSD and cost more symbols to borrow; it merely accepts that money can be owned as an asset, and hired out for a fee like land, labour and production equipment. In the words of a textbook: “If someone else wishes to obtain current command over resources that I presently own, I cannot be induced voluntarily to give up that command unless I am rewarded. That reward will be the interest received.”[242]

In other words, interest is charged because ownership allows it and because competition compels it – which comprises an explanation but not a justification. Even as an explanation, it seems out of date, because for centuries, most lending has been done not by actual owners of the money lent but by banks and other institutions with whom others have merely stored money. Furthermore, as the next section explains, most money leant nowadays is not even truly owned, merely recorded in bank ledgers and treated as owned.

Ultimately, interest allows those with possession or claim, but not necessarily actual ownership, of plenty of wealth-symbols (whether gained by skill, deception, sheer hard work and perseverance, extortion, or just plain good luck) to determine, by their willingness or reluctance to lend, what new wealth is created. And the willingness to lend depends simply on whether lenders expect borrowers to be able to repay the loan and afford the interest charges. For lending to businesses, this in turn depends almost entirely on lenders’ estimates of borrowers’ potential to profit from their ventures. (…ackers…)

Hence, mostly sure-fire profit-returning or risky higher-profit-returning wealth tends to be created. Wealth that requires money in advance to initiate, but which has genuinely optimising effects that cannot be measured in terms of profits or delusionary L$D-prices – for example, homes for the homeless – tends not to be created by the market, only (if deemed essential) via government taxation. So, the territory further loses priority to the map (“if it says Utopia, then that must ‘be’ where we ‘are’”).

Of course, borrowing means debt, and debt (as chapter 1 explained) requires growth, which in turn requires more debt – a dangerously unstable dynamic prone to collapse. Aggravating this dynamic, and making interest even more dubious, a delusional set of banking practices allows the lending of a great deal more money than the amount actually possessed…

4.3 Liquid Delusion

“A ‘sound’ banker, alas! is not one who foresees danger and avoids it, but one who, when he is ruined, is ruined in a conventional and orthodox way along with his fellows, so that noone can really blame him.” – John Maynard Keynes[243]Savings banks, commercial banks, investment banks, trading banks, finance companies, trust companies, savings-and-loans companies, building societies – their exact rules of operation vary, but no shortage exists of firms who accept money for safekeeping and pay interest to their depositors for the privilege. (All such firms will usually be referred to henceforth as banks.)

People have been leaving money with others for safekeeping since ancient times, but the earliest ‘modern’ banks appeared ‘only’ about 800 years ago in Tuscany in northern Italy. The Tuscan banks can be called modern because they began the process of replacing cash (at the time, coins full of precious metals) with pieces of paper representing a promise to pay cash. These early experiments in fiduciary money, like primitive credit cards, saved merchants from the bother of transporting unwieldy volumes of cash around with them on their often wide-ranging journeys. In time, Italy’s banking practices spread to the Netherlands, where the Bank of Amsterdam was formed in 1609. This bank, initially just a place of deposit, soon took to lending money in ways barely distinguishable from current practices.

When a bank lends money, it alters its records by opening a credit account. Then or later, if required, it hands over to the borrower the corresponding amount, either in cash – which it obtains from that left with it by depositors – or as a cheque – which can later be cashed. More often these days, no cash is handed over, instead all the transfers are merely recorded in the relevant accounts. Either way, as soon as even one credit account is opened, the money available to all of a bank’s customers, according to their accounts, exceeds the actual cash deposited. On the books, credit creates money; in reality, it merely shuffles it around. (…lucre…) Repayments of credit – whether by cash, cheque or transfer from deposit accounts – have the reverse effect: they reduce credit accounts (eventually) to zero, leaving a bank’s recorded customer liabilities equal to its actual cash stocks – or at least they would if banks didn’t always have outstanding loans.

So, out of nothing credit comes, and to nothing it returns. Freshly created credit thickens the economic flow by re-circulating over and over an otherwise stagnant savings pool, but repayments thin the flow back to ‘normal’. However, the compounding interest paid for credit concentrates the ‘normal’ economic flow in the direction of banks, transferring to them money from someone else’s pockets (see section 1.5) – and not just a little either. Typical home mortgage loans, when not repaid until the end of their multi-decade terms, net lenders interest worth several times the amount loaned. Quite a reward for shuffling paper.

Of course, credit-creation can only occur because banks have the unique legal power to adjust their accounts and be taken literally, and to access their depositors’ cash with little restriction. Yet, for any bank with even one credit account open, if every account holder wanted to withdraw all of the money recorded in their accounts, this could not be done – because the total recorded in all of the bank’s customer accounts would exceed the actual cash deposited. Hence, banking involves certain inherent risks, as many have discovered over the years eg. the USA’s IndyMac, and Savings-And-Loan companies, including Washington Mutual; Australia’s Tricontinental, Pyramid Building Society and Estate Mortgage Trust; Iceland’s Landsbanki; many nations’ Bank of Credit and Commerce International, and Bear Sterns…

Sometimes, a bank fails: it finds itself with insufficient cash to meet depositors’ withdrawal demands, either because it made too many bad loans (those ultimately not repayable), or because its depositors lost confidence upon hearing of many bad loans – or even upon hearing rumour of them. Whatever the reasons, in a ‘bank run’, many depositors come at once for their money, but with much loaned out to others, insufficient for all is left. The bank turns away those of its customers who miss out, closes its doors, and calls in its loans (which often results in collateral acquisitions, because loan contracts invariably authorise banks, should repayments prove tardy or not forthcoming, to legally confiscate borrowers’ assets as their own, up to the value of the outstanding amount). Then the bank sells its assets, and returns the proceeds to its creditors, owners and depositors – in that order. (…dibs…) Rarely if ever is enough scraped together to cover everyone’s losses, and so the economic flow usually thins. But this non-optimising effect can sometimes spread considerably: in 1933, for instance, after four years of bank runs, depression, and diminishing confidence in the economy – against which the magic wands of bankers’ pens have no power – it took a presidential declaration of a week-long ‘bank holiday’ to stop the entire USA banking system from folding up.

Many different ‘remedies’ have been tried to prevent bank failures – or at least to minimise their very non-optimal effects – but in Galbraith’s words, “all were a response to bitter experience. At all times, men were torn between the immediate rewards and costs of excess and the ultimate rewards of restraint. It was only after the first were experienced that the second were legislated.”[244] For instance, after the USA banking system all but collapsed in the Great Depression, the Roosevelt administration attempted to resurrect it using insurance. During the 1933 bank holiday, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) was formed, backed by the federal government to guarantee all deposits up to a maximum (currently) of $250,000 per account owner. Funded by insurance premiums paid to it by banks, the FDIC seemed to adequately serve the USA banking system – until the mid-1980s when cracks began to show.

Like any other insurance firm, the FDIC can lose its liquidity – which is to say, its excess of cash and cash-convertible assets over its debt commitments. This can occur if enough banks insured by it lose their liquidity and go bust. Encouragement for just such a turn of events began with President Reagan’s deregulation of USA financial institutions in 1982, which legally allowed them to take extreme and sometimes greedy risks; hence, when later property market downturns and the 1987 stock market crash wiped out hefty proportions of the value of many banks’ assets, some found themselves non-liquid. In particular, the USA’s Savings-And-Loan companies (S&Ls) went bust in such great numbers that the FDIC had insufficient funds to cover all the losses. At first, the FDIC allowed the S&Ls to stay in business in the hope that they would trade themselves out of trouble, but most only got into deeper trouble. Eventually, the FDIC had no option but to shut down the failed S&Ls, seize their assets, sell them, and with the proceeds pay creditors, owners and depositors.

As a government body, the FDIC can make up its shortfall of funds by borrowing from the government Treasury, but this means ultimately that taxpayers foot the bill. (…brass…) Hence, by the end of 1999, the entire S&L debacle had cost taxpayers $124 billion.[245] So, when bank failures occur in great numbers, the FDIC merely acts as an intermediary in the economic flow – a go-between for redistributing money from the nation as a whole to those of its members who lose because of bust banks. Paper-shuffling squared. The process can work very inefficiently: it has been suggested that inexperienced FDIC staff sold S&L assets at absurdly low, possibly colluded prices, and that, for political purposes, the FDIC delayed action until after the 1988 presidential elections, an act which ultimately doubled the S&L losses and, consequently, the FDIC/taxpayer debt. But then, as Galbraith wrote in regard to the debacle: “The free enterprise system fully embraces the right to inflict limitless damage on itself.”[246]

Not all nations insure bank deposits as an attempt to prevent or minimise bank failures, but most operate ‘central banks’. Central banking began with the founding of the Bank of England in 1694, originally as a private bank, but soon after as “largely an agency of the government. The Bank of France was established as a governmental institution by Napoleon in 1800.”[247] The USA, since Independence, has had several tries at a central bank; the current version – the Federal Reserve System – was founded in 1913. In Australia, the counterpart is called the Reserve Bank.

Although central banks operate (like banks) as businesses, seeking and usually winning profits, they also have wider responsibilities and are occasionally nationalised. They exist mainly to regulate banks and their lending practices. But like insurance, central banking does not always work. The USA’s Federal Reserve System could not stop the banking collapse of the Great Depression or the bank failures of the Great Recession, or less dramatic failures in between. In other countries, too, bank failures have persisted despite the many forms of central banking. Nonetheless, central banks do sometimes help keep banks liquid, by regulating the amount of money available to an economy and the amount that banks can lend – in other words, by managing a nation’s money supply (roughly speaking, the ‘volume’ of its economic flow).

A central bank regulates the money supply in three main ways. Firstly, it sets ‘reserve requirements’ – a minimum percentage (usually) of bank deposits to be kept at the central bank ‘in reserve’ (enough to satisfy all depositors seeking their money in normal circumstances but not in a run). When business booms, however, and profits are thought to be guaranteed from doing so, banks will keep less money in reserve (and lend more) than is required – at least until auditors investigate carefully enough. They may also employ other more creative accountancy practices to reduce their official reserve. In contrast, during dark economic times, banks may keep more in reserve than is required, due to reduced numbers of willing new borrowers. Just as the actual reserves vary, the reserve requirement itself depends on the country, the type of deposit (time or demand), the size of the bank, and the economic, political, and psychological climate. In most cases, the figure ranges from two to ten percent, with no country above thirty percent (in 2011), but a few at zero.[248] How reserve requirements actually affect the money supply and banks’ lending practices can be best explained using an example.[249]

Assume, for simplicity, that for all banks and all deposits, the reserve requirement is set at ten percent and that all banks meet this requirement. Thus, if a bank receives a new $1,000 deposit, it sends $100 as a reserve to the central bank, and lends the remainder. But the loaned $900 is eventually spent, and sooner or later, it passes to people who choose to deposit it in one or more banks. These banks, in turn, send ten percent of the now re-circulated $900 ($90) to the central bank, and loan the remainder ($810). But the new loans, too, are eventually spent and re-deposited in banks, which send ten percent to the central bank, and lend ninety percent ($729) – which ends up re-deposited to start yet another cycle – which eventually starts another – and so on. When the final cycle is reached, money ‘created’ by the entire banking system as loans, because of the original $1,000 deposit, will total $9,000, and reserves, $1,000.

But although the depositors of the original $1,000 and its many re-circulations will have bank accounts ‘proving’ that, between them, they ‘own’ $10,000, only the original $1,000 will actually exist as cash – the extra illusory $9,000 will ‘exist’ only in bank records as a result of re-circulating the actual $1,000, over and over. So, no new money is printed, merely recorded. (Of course, modern accountancy’s version of the loaves and fishes miracle can work only as long as everyone doesn’t come at once for their money.)

The proportion by which money can be expanded on paper by the ‘fractional reserve’ banking system just described equals the reciprocal of the reserve requirement – at ten percent, the recorded money supply equals ten times the actual; at five percent, twenty times; and so on. Approximately. In practice, people may not need to borrow all that banks make available for borrowing, banks may not want to lend it all, and some loans may not return to banks but be kept under mattresses, with illegal ‘black’ markets, and so on.

Central banks can regulate banks by adjusting the reserve requirement: raising it means that banks keep less and so reduce lending, lowering it means banks have more to lend. The ‘multiplier effect’ that sees one deposit re-circulated many times as loans also works in reverse: reduced loans even for one bank have the same contractionary effect on others. However, the potential for this approach to cause liquidity problems for riskier banks tends to result in it being used less often than other regulatory options.

Central banks more often and more easily affect the money supply by altering what is called the ‘bank rate’ or ‘rediscount rate’ – the interest rate they charge, as lenders of last resort, for their loans to banks. Raising the bank rate either reduces the amount that banks are prepared to loan, or, more likely, causes their own interest rates to be raised – in either case, borrowings tend to reduce. Lowering the bank rate has the opposite effect of increasing the money supply.

A third method employed by central banks to regulate the money supply involves the very curious subject of ‘bonds’. Bonds are issued by business companies, including banks, as well as by various government departments, especially Treasury, and by state-owned enterprises such as the post office. Like paper money, bonds have no intrinsic value in themselves, and act essentially as interest-bearing IOUs: they are offered at a set interest rate and with a promise that the bond-seller will repay the purchase price after a set period (at ‘maturity’). Companies sell bonds because they expect to use the money so gained in ways that will make them sufficient profits to not only repay the ‘bondholders’ their money plus interest, but also to make a tidy profit themselves. They do not always succeed. Of course. If issuers of bonds go bust, proceeds from the sales of their assets go first to those they owe money for goods, services and taxes, and then, if any is left, to bondholders. Sometimes, holders of bonds issued by companies which go bust get nothing back, as happened with nearly all of the USA’s railroad bonds during the Great Depression.[250] Bonds that stop paying their promised returns are said to have ‘defaulted’ (the same term is used for loans that can no longer be repaid by their borrowers).

Central banks regulate the money supply by buying and selling government bonds, activities called ‘open-market operations’. Operation seems an appropriate word. Study the following example very carefully – the central banker’s pen ‘is’ quicker than the eye.

If a central bank buys (say) $1,000 of government bonds – from the Treasury or second-hand from someone else – it pays “by a check on itself”,[251] recording this in its official books as increases of $1,000 in its assets (the bonds) and $1,000 in its liabilities (the cheque). When the bond-seller cashes the cheque or deposits it at a bank, or passes it on eventually to someone else who does the same, the bank receiving the cheque ‘cashes’ it at the central bank, which does so by again recording it as done: the cheque liability is removed and replaced by an increase of $1,000 in the reserves of the bank cashing the cheque, which means (with a ten percent reserve requirement) that an extra $9,000 can be lent by the banking system overall. Because, at some stage, $1,000 in new notes will need to be printed to match the increase in the record of bank reserves, central bank purchasing of government bonds is often referred to as ‘printing money’. It also has a more benign and vague euphemism: ‘quantitative easing’. Since the turn of the century, it has been used extensively by the USA, Europe, Japan, and other nations after they had reduced their rediscount rates to zero percent or barely above.

In a similar fashion, if a central bank sells government bonds, the cash or cheque used to buy them reduces some bank’s reserve account with the central bank, which reduces that bank’s and the system’s overall lending capacity by nine times as much (assuming a ten percent reserve requirement).

The central bank gains by either operation: bond sales return it cash or else a ticket to plunder a bank’s reserve account, bond purchases return it interest from governments until the bonds mature – a handy arrangement for a profit-seeking business like central banking.

So, the convenient fictions of bonds, mere promises of future security, by ‘mutual’ agreement, and via the legally granted powers of central banks, ‘allow’ money to be created by the recording of it as done – and once recorded, everyone treats it as so. Just like the shuffling of fractional reserve systems that turn a deposit into several loans, money magic indeed. But when a central bank buys bonds with cheques on itself, and ups its assets and liabilities by the same amount, so recording its liquidity as unchanged, it can do so only because, unique among economic game-players, it has a mint handy to keep up with its cheque-writing propensities. Even banks have to work harder than this to make money.

Purchase of a government bond costs a central bank nothing, yet gains it interest. The government or bond-seller also gains the sale’s revenue – handy for covering a budget deficit, bailing out the FDIC or even the entire financial system, paying for the Vietnam war, or (in theory at least) trying to boost spending during a recession. The economy even gets more money to spend. Dare we believe that everyone wins? A positive-sum game? Well, yes. But not for long. Because governments have to pay interest for the bonds they sell, and because “government bonds have prior right to funds produced by taxes”,[252] the apparent free gift more closely approximates hire purchase.

Governments sell bonds for similar reasons to business firms: governments often see bonds as worthwhile investments because the revenue gained from their sales can be used to encourage economic growth, which not only is expected to work to the benefit of the nation they are meant to be managing, but also means extra tax revenue (from extra income) to pay off the bonds and their interest. Hence, though frowned on by neoclassical theory, governments can – and usually do – run budget deficits year after year, without any need for compensating surpluses, as long as the following year’s economic growth is expected to increase revenue enough to cover the interest on this year’s escalation of debt.

But the process remains a gamble: if growth does not occur, revenue does not increase, and the debt mounts. Governments then have only a few options. Firstly, sell off state-owned assets like banks, airlines, and electricity and water companies – although such ‘garage sales’ involve a lot of effort and mess, and can’t last forever. Or raise taxes and/or cut spending – not always politic, but sometimes necessary to keep debt manageable. Or, like a snake swallowing its tail to avoid starving to death, a government can try to foster growth to pay off bond debts by going further into debt, either with banks or via new issues of bonds. Certainly, the USA Federal Congress, despite inevitable ceremonies of protest, has a persistent habit of raising the legal ‘limit’ for the total value of outstanding government bonds whenever it feels the need. But of course, a snake cannot swallow its tail indefinitely.[253]

If government bonds were to be defaulted, the central bank’s assets would diminish by the value of its unredeemable bonds, and liquidity would evaporate. No more central bank, no more fractional reserve banking system, and no more economy (‘optimal’ or otherwise). To avoid such a disaster, to maintain the system, and to keep its own debts in hand, governments must sell assets, cut spending, and/or raise taxes as necessary. So, although a bondholding minority benefit, the system is maintained ultimately at taxpayers’ expense. So also, we have ‘no’ option but to believe (or at least hope) that, despite mounting ecological and social decay, the future will always provide greater optimality and more capacity to repay debts incurred now to keep the system going. Meanwhile, eroding that belief, government and central bank debt mounts – along with business, consumer, and most other forms of debt[254] – in nominal terms, in real terms, as a percentage of GDP – here, there, and in most places – and most of the time since World War 2. ‘Smith’ wrote that “the accumulation of debt began as a logical response to the era of paper money”,[255] but a snake swallowing its tail must at some stage stop – if only to throw up.

Before then, however, the snake will gorge itself on many imaginary meals, and not just those provided by banks and governments…

4.4 Speculation

“Face it – you’re too busy to lose the kind of money you’re making. It’s time to put our strong hand in your pocket. Turn it over. Give it up. Submit to Boom Dot Bust… A usurer-friendly, randomly managed, ethically indifferent, cash vacuum. From U.S. Whatgate Plus.” – The Firesign Theatre[256]As mentioned, to gain investment money, businesses sometimes issue bonds – either asset-secured ‘mortgage’ bonds or asset-unsecured ‘debentures’. Companies also acquire money via two types of ‘stocks’: ‘preferred’ stocks yield a fixed interest return (like bonds), and ‘common’ stocks return annual payments called ‘dividends’, the value of which depends on what’s left of company profits after first being apportioned to bondholders, then to preferred stockholders, and then to the company itself (as ‘retained’ profits) for investment or expansion purposes.

Bonds and stocks are together called ‘securities’, but unlike bonds, stocks entitle buyers to part-ownership of the issuing company. Stocks are issued in what are called ‘shares’ (a word often used synonymously for ‘stocks’). If a million shares of stock are issued (often in minimum lots of hundreds or thousands), any one share corresponds to ‘ownership’ of a millionth of the company, including proportional voting rights for some operational and policy decisions.

Some shares are not made available to the public, but are retained by the founders of issuing companies (at zero cost, because paying oneself for anything involves no exchange.) Founders of companies naturally aim to retain a controlling majority of shares to ensure their own policies rule, but circumstances sometimes prevent this: firms can and often do maximise their profits most easily by gaining a majority of the shares of smaller, more profitable companies. Indeed, profitable businesses are often bought by so-called ‘private equity’ groups of financiers with no relevant experience of managing those businesses, who then pay the loans taken out to afford the purchases via the profits of the companies obtained, after which they sell the businesses at yet another profit after having done nothing as owners to enhance their operations or even keep them competitive.[257] This never-ending process of ‘buying out’ and ‘taking over’ further concentrates business, involves a lot of debt, risk and effort that could be put into more productive ventures, frequently leads to inefficient and hastily conceived organisational restructures based on massive staff cuts for those taken over, and generally replaces the practical knowledge of original business owners with the operational ignorance of financiers. Hardly optimal.

Any legally registered business company can sell stocks (or ‘go public’ as the process is sometimes called), although state approval and licenses may be required in some countries for issues over a certain size. But while the actual value and amount of shares issued ultimately depends on a firm’s perceived ability to pay returns to stockholders, sometimes it seems like companies just play ‘pick a number – any number’. Consider this example given by ‘Smith’: “In 1972… [t]he Levitz brothers… of Pottstown, Pennsylvania, were furniture retailers whose company netted $60,000 or so a year. Then the company noticed that sales were terrific when they ran the year-end clearance sale from the warehouse… [T]hey added more warehouses, and the company went public… At one point, it was selling for seventeen times its book value, one hundred times its earnings, and… [the brothers] had banked $33 million of public money for their stock, and they still held $300 million worth.”[258] (…pelf…) More money magic, reminiscent of money-printing and credit. Yet impossible without L$D.

Because the profitability of a company determines the returns to common stockholders, and the certainty of returns to holders of bonds and preferred stocks, it also influences the demand for the company’s securities, and hence – via L$D – their prices. “Those who first find out about the increased present or future profitability of a company will bid up the price of the shares of stock in that company, and those who first find out that the company is going to be less profitable in the future will, by their selling, cause the price of the stock to fall.”[259] Of course, people find out different things, and think differently, and ‘know’ differently.

In fact, people mostly speculate as to the prices of securities, depending on what they think they know and what they expect. Perceptions rule. It makes for extreme activity. For instance, some people might expect interest rates at banks to rise enough to cause their own fixed interest returns on bonds and preferred stocks to be surpassed. They would therefore probably be prepared to sell their securities at a discount. Likewise in reverse: if bank interest rates fell or were expected to fall, the market valuation of bonds and stocks generally rise. But a re-sale of any security occurs only if both parties to the exchange believe they gain an advantage from it, which largely depends on them having different circumstances and/or expecting (or hoping for) different futures (such as those in which interest rates change in opposite directions).

Much speculating over, and buying and selling of, securities occurs in what (less than correctly) is usually called the ‘stock market’. Yet “for most stocks on any one day, only a fraction of 1 percent of the total number of shares owned is traded.”[260] All who ‘play’ the stock market aim to buy cheap and sell for a profit, but of course, not all can succeed. Nevertheless, the stock market’s potential for quick and easy profits lures people to it – those with spare cash who think they have an eye for picking winners. Some even turn it into a business: financial institutions like mutual fund companies exist almost solely for the purpose of investing clients’ money in securities. Many other people indirectly speculate through insurance and superannuation companies, and even banks, who all invest at least some of their clients’ savings in stocks and bonds and whatever else seems likely at the time to pay off. But although the totality of all (international) buying and selling of securities can result in generally rising security prices (aptly called ‘bull’ markets) or falling prices (‘bear’ markets), ultimately, even well “managed funds with well-paid managers do about the same as a totally random portfolio… that is what the statistics say.”[261] And of course, in a zero-sum game, those who win do so only because others lose.

A few can’t help but win. People in privileged positions of trust and/or specialisation, such as company directors or lawyers, can find themselves in possession of information – unavailable to the general public – indicating highly probable price movements of specific securities. For instance, share prices often rise after a company is taken over – which happens all the time – so anyone in the know beforehand could profit by buying shares prior to the official take-over announcement. Such ‘insider trading’ is not legal, but the extent to which it nevertheless happens can only be guessed. Likewise for the extent to which creative accountancy fiddles the books…

If L$D-prices mislead, then some of the work of accountants on company revenue and expense ledgers, which determine official profits, simply deceives – especially in recent decades. To use one example provided by Satyajit Das, “Traditionally, earnings are recognised when cash is or is about to be received, progressively over the life of a contract. Mark-to-market accounting allowed revenues over the entire contract life to be recognised immediately.”[262] In an accountant’s own words: “Accounting today permits a shaping of results to attain a desired end. Accounting as a mirror of activity is dead.”[263] Reiterating this differently, “the head of one of… [the USA’s] major drug companies put it quite succinctly: ‘One good accountant is worth a thousand salesmen’”[264] – at least as long as he or she can get away with it. In the most notable example of recent years, Enron Corporation reported high profits for years, but in 2001, soon after its widespread accountancy fraud was discovered, the company went bankrupt.

Subject to such manipulations, and the speculations of those who do not know what is happening, securities markets prove less than secure. Yet some securities prove more prone to trouble than others. In the 1920s, for instance, many financial innovators developed what were called ‘investment trusts’ and ‘holding companies’ – businesses which did nothing more productive than issue securities of their own to invest the money so raised in securities of other companies. (…boodle…) Galbraith explained the inherent risks of such an arrangement: “if anything interrupted the upward flow of dividends – from which the interest charges on the upper-level [investment trust/holding company] bonds had to be met – the bonds would go into default, the whole structure collapse in bankruptcy.”[265] And of course, the stock market crash of 1929 provided the unsought interruption: the dramatic fall in prices of securities savagely cut the market valuation of business assets, and thus evaporated much liquidity; less profitable as a result (if not bankrupt), most companies could only pay much smaller (if any) dividends, which thus ended the free ride of investment trusts and holding companies.

Not that the security-issuing methods of the 1920s constitute an exception. As Galbraith put it: “The holding-company promotions together with the investment trusts… were, in all respects, the precursors of the conglomerates, performance funds, growth funds, offshore funds, and real estate investment trusts… [which] were to grace and then ungrace the financial scene of the sixties and seventies.”[266]

The junk bonds of the 1980s also deserve mention: high-interest bonds issued for high-risk business ventures lacking alternative funding but rarely profitable for long, and hence rarely paying bondholders their expected returns beyond the short-term. Michael Milken, a USA ‘stockbroker’, achieved brief fame by arranging junk bond issues largely to finance risky business takeovers. Milken made much personal profit in the process (“$550 million in 1987 alone”[267]), but his junk bonds nonetheless turned quickly to junk, most investors lost their money, and Milken lost his freedom.

The subject would not be complete without mention of ‘mortgage-backed securities’ (MDSs) – also known as ‘bundles’ or ‘collateralized debt obligations’ (CDOs). When house prices were steadily climbing in the 1990s, some financial innovators realised they could profit by purchasing mortgages from banks, bundling them together, and then issuing securities backed by the mortgagees’ repayments. Like other borrowings similarly transformed by financial wizardry into ‘securitized debt’, these MDSs were then traded like any other type of security. As long as borrowers kept paying their mortgages, MDSs made their owners significant profits. But MDSs went sour after interest rates rose and housing prices, especially in the USA and Britain, began to fall in 2006. Soon, many borrowers defaulted on their mortgages, and the MDSs turned to junk, which eventually prompted the investment company Lehman Brothers to make the largest ever USA bankruptcy filing (over $600 billion) – all of which triggered the credit crisis and stock market plummeting of 2007-08 that ushered in the Great Recession.

An increasing number of other very insecure securities could also be explained, such as ‘derivatives’, ‘shorts’, ‘swaps’, but these too-clever-by-half exercises in self-deception – glorified IOUs and bets upon gambles – differ only in detail; like all the others, they conjure up cash flows with almost as much ease as they lose them.[268] As Keynes remarked: “The social object of skilled investment should be to defeat the dark forces of time and ignorance which envelop our future. The actual, private object of the most skilled investment today is ‘to beat the gun’,… to outwit the crowd, to pass the bad, or depreciating, half-crown to the other fellow.”[269] This point is further made by the vast amounts invested in the most insecure securities: by 2006, securitized debt and derivatives comprised 79 percent of all the world’s liquidity, equivalent to more than five times global GDP (with bank loans adding up to 19 percent, and only two percent in cash, reserves, and bank deposits held by central banks).[270]

Of course, various authorities have responsibility for preventing or stopping unfair and dangerous securities practices. Some activities are even forbidden by legislation (usually after they have caused a lot of damage). But the actions of some authorities, such as the New York Stock Exchange (founded on Wall Street in 1692) can themselves seem unfair and dangerous. Referring to events during 1970, when the USA stock market fell almost as markedly as it did in 1929, ‘Smith’ had this to say: “A firm is supposed to have a certain amount of capital in relation to its obligations… As firms began to fall grossly behind in their capital requirements, they would be suspended from dealings by the New York Stock Exchange. Except for very big firms… Said Robert Haack, president of the exchange, ‘We simply can’t afford to have a major firm fail.’… [Principally because] the announcement of a suspension of a major firm might cause a run on all brokers, even ones in good shape, by worried customers.”[271]

But Stock Exchanges can only do so much – they certainly cannot prevent the market from falling. Stock markets have crashed dramatically not just in 1929 and 1970, but also in 1987 when stock prices fell by twenty to sixty percent in a matter of days.[272] Indeed, on October 19, 1987, aided by computer programs that automatically sold stock as soon as their prices fell to certain levels (undoubtedly incorporating the traders’ assumptions, biases and perceptions),[273] stock prices fell more sharply (in percentage terms) than on any single day before or after (over 22 percent in the USA). A year later, another dive of around ten percent occurred. Japan’s stock market fell less than others in 1987, but mostly declined for the next twenty years, its ‘average’ dropping from almost 40,000 to barely 7,000 over that time. As section 5.2 explains more fully, such changes have their effects. According to some analysts, the 1987 crash made a major contribution to the recession of the early 1990s, by filling the interim period with unstable short-term curative attempts and alternative investment strategies that ultimately could not be sustained. The market fall that followed the ‘dotcom bubble’ of the late 1990s (a period marked by overly enthusiastic investment in Internet-based companies) has also been blamed for leading to similarly poor policies (such as too low interest rates) that helped create the credit crisis of 2007 – which in turn led to even lower interest rates and even easier money policies of central banks, which many consider to be leading inexorably to yet another financial crisis.

Regardless, the stock market – inherently and irremediably unstable and uncontrollable – must crash sometimes. As Galbraith explained: “Speculation occurs when people buy assets, always with the support of some rationalizing doctrine, because they expect their prices to rise. That expectation and the resulting action then serve to confirm expectation… [If] enough people are expecting the speculative object to advance in price… [they] make it advance in price and thus attract yet more people to yet further fulfil expectations of yet further increases… If anything serious interrupts the price advance, the expectations by which the advance is sustained are lost or anyhow endangered. All who are holding for a further rise – all but the gullible and egregiously optimistic, of which there is invariably a considerable supply – then seek to get out. Whatever the pace of the preceding build-up, whether slow or rapid, the resulting fall is always abrupt.”[274] And of course, hopes and expectations cannot rise indefinitely, and serious interruptions do occur – so, the stock market can only bear so much bull.

Stocks and bonds cannot help but cause trouble, their markets doomed to sometimes turn into over-valued ‘bubbles’ that must inevitably burst. Securities markets divert the economic flow, channelling money into companies keen to profit, in return for receipts whose values and interest/dividend returns swell and shrink, oscillating as perception and misperception of profitability changes. A comment by Das about a particular company in 2000 seems more generally applicable: “Stock prices no longer represented any real underlying business or earnings. It was monopoly money, convertible into something real if others believed in its value.”[275] Necessarily variable, security values can mislead economies into thinking they have, or are making, great wealth, when instead, like banks and central banks, they may merely be devoting much of their efforts to a non-optimal shuffling of unproductive wealth-symbols. But securities are not the only things that suffer from these problems; and neither are they unique in developing a credulous following who sooner or later can’t maintain their belief.

Land and property values also go up and down depending on L$D. Usually, in the developed world, they mostly rise. But sometimes they rise too quickly and then quickly fall. The falls don’t last long – usually. The Great Depression, however, saw such a steep fall that it was not reversed until the 1950s. Speculators who can pick the trends tend to clean up. Just as they do with commodities: anyone anticipating higher prices because of poor crops or lowered production can buy now or order at current and contractually binding prices, then (if expectations prove correct) reap large rewards by re-selling at higher L$D-prices. The same advantages can be gained by storing a surplus for later, when supplies are expected to run low.

Speculation also now runs rife in regard to currency exchange rates: only about three percent of currency market flows deal with “actual trade and investment… The rest is… speculative capital zooming around the globe at the speed of light along fibre-optic cables in search of profits.”[276] The habit began decades ago. As section 4.1 explained, currencies were still fixed when the USA severed the link between its dollar and gold in 1971, but national growth rates and debts, balances of payments, and government budgets, often told tales different to the stories implied by the exchange rates. So, people learnt to distrust or favour certain currencies – some seemed overvalued, others undervalued. To cope, the dollar was soon devalued, the price of gold raised, and newer more ‘agreeable’ exchange rates fixed. But this didn’t help much.

As nations grappled with the uncertainty of no standard – no key currency against which to measure their own – as over-issues and under-issues of money loomed big in fact and imagination, L$D went into overdrive. In the scramble, prices and wages rose here and skyrocketed there. A textbook explained the results: “differences in price levels tended to create lasting deficits and surpluses. Some currencies were weak, while others were strong. The field was now left open for speculators to move in. They started to sell the weak currencies and buy the strong ones. They could hardly lose under a system of fixed exchange rates as speculation tended to become a riskless one-way operation… It has been estimated that the speculators made net profits of at least $5 billion during the crisis years 1967-73. These losses were born by the various central banks in their struggle to defend existing parities.”[277]

After a few more attempts at currency revaluations, exchange rates were floated in 1973. Change had become too swift and perception too confused to leave them fixed. The majority of economists, especially those employed for their counsel by governments, gave their approval to the move, believing that no other option existed (and few have changed their minds since).

After the 1973 float, any currency “was worth, on any given day, what the buyers and sellers said it was worth… [T]he markets… follow… Gresham. Sell the weak currency and buy the strong one. Better, borrow the weak currency – pay it back when it’s still weaker – and buy the strong one.”[278] Money is thus treated like a commodity, and exchanged accordingly.

But L$D-trading in wealth-symbols creates problems even for strong currencies. Nations can acquire too much of a strong currency, then reduce the excess by selling it cheaply, enough of which lowers the average exchange rate, and so ‘weakens’ the currency. To strengthen currencies, governments and central banks often resort to raising interest rates above those of other nations; this motivates more trading of other currencies for the local version (in order for it to be deposited in local banks) and, hence, increases demand for it, which L$D-pushes up its exchange rate. But locals also pay more for borrowing, so it involves a price. And it often just encourages other nations to raise their interest rates to ‘enhance’ their currency in the same way – another potential vicious circle. More regularly, central banks try to stabilise their currencies and compensate for market excesses by themselves buying and selling different currencies, using reserves put aside for just such emergencies, or raiding petty cash as the need fits.

Not surprisingly, floating exchange rates have not made for much stability. Indeed, in the modern floating world, some nations only have to burp in order to rock others’ boats. For instance, because Germany and Japan import all their oil, their balance of payments surpluses reduced (and sometimes turned to deficits) when OPEC (the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries) raised its oil prices in the 1970s. The mark and the yen consequently lost value – but they soon regained it, because the German and Japanese economies produced and exported more goods, and so gained the extra income necessary to pay for the costlier oil. The USA dollar fared less well at the time; however, because OPEC has a lot of dollars in its many bank accounts around the world, when the dollar’s value goes down, OPEC at least considers raising oil prices to compensate – yet another vicious circle hard to exit.

But instability arises in an even more fundamental and less easily compensated way: because the behaviour of floating foreign exchange markets – like stock, bond, property, commodity and other speculative markets – depends mostly on the not always rational beliefs of traders, self-fulfilling prophecies tend to rule. Hence, if the latest official estimate of inflation is calculated as a mere tenth of a percent more or less than the average anticipated by self-styled authorities, then currencies – and stock markets and interest rates – can fall or rise out of all proportion. Similarly, if (‘say’) a somnambulant federal treasurer (without announcing any new information, just opinion) casually includes the phrase ‘banana republic’ while publicly speculating about his nation’s future, traders can be inclined to believe it – prompting the home currency’s value to sink like a stone.[279] Thus, economies using floating exchange rates must cope with how ill-considered hyperbolic spoken thoughts, even whims, of those with influence and/or a high-profile can greatly and adversely affect economic parameters and, more importantly, in a very non-optimal fashion, the lives and livelihoods of many game-players. Fixed exchange rates had their problems, but in the words of ‘Smith’, the “trouble with floating rates is that they bounce all over the place.”[280] Especially in periods of doubt and uncertainty.

Keynes called money a veil, but what a tangled web we weave. Preceding chapters explained why capitalism does not produce optimality (despite what neoclassical theory claims), but adding money to the picture makes for even less optimal results. Today, with no backing by precious metals, and with no key currency to underpin others and so define ‘value’, we just print money – at central banks, certainly, but effectively also through credit accounts, security issues, and exchange and property markets. Tickets. Our estimates and perceptions of value, measured without a yardstick. And our energies go into speculating about those tickets, into diverting the economic flow of money onto ourselves without improving the state of real wealth. Yet though the records and accounts and receipts and ledgers and market indices often speak of utopia, oblivion always catches up. The records must be believed to be maintained, but sooner or later, the state of real wealth is perceived to deny the records. Belief wavers, the so-called ‘speculative bubble’ bursts, and speculators and non-speculators alike are crushed together by the collapse. The greater the misrepresentation on paper, the greater the toll. Yet given our addiction to L$D, and its encouragement to mistake the map of money as the territory of wealth, what else could result but multiple insoluble problems and eventual collapse.

And given the constant turmoil – the endlessly shifting values of currencies, stocks, bonds, interest rates, deposits, debts, reserves, and derived fabrications – what else could result but frequent and often undesirable changes to the L$D-prices assigned to real wealth, their inherent inaccuracy corrupted further by inflation…

4.5 Inflation

“…inflation is basically an endemic consequence of the operation of the economic mechanism” – Robert L.Heilbroner[281]When prices generally rise, this is termed ‘inflation’; when prices fall, ‘deflation’ (or ‘negative inflation’). An inflation or deflation rate estimates the average rise or fall in prices over a given period of time, usually a year. Naturally, some individual prices rise or fall by more than average, some by less, and a few in the opposite direction to that of the many. But in keeping with most other economic ‘science’, even the average rate of inflation or deflation can only be estimated, and only after adopting convenient simplifying assumptions.

The most commonly used method for estimating inflation employs what is called a Consumer Price Index (CPI). After measuring consumer spending habits, economic statisticians define an average or ‘typical bundle’ of goods and services that is purchased, according to the measurements, by an average or ‘typical consumer’. The typical bundle’s actual cost is then used as an index of consumer prices: inflation of ±x percent means ±x percent change to the cost of the typical bundle. But no bundle stays typical forever: consumer spending habits adjust as tastes change, as the quality of products alters, as new goods and services appear, and as old ones disappear. Hence, typical consumers may spend more or less than before, and receive more or less – quantity and/or quality – in return for their money. Economic statisticians try to take this into account: according to a textbook, “if the typical bundle becomes glaringly out of date…, the bundle is revised and the old index is spliced to the new through statistical jockeying designed to smooth the transition.”[282] This applies not just to the CPI but also to the wholesale price index, the investment price index, and all the rest.

But although the exact rate of inflation can be debated, not so its effects. For those whose incomes do not increase in line with inflation, it steadily reduces their ability to buy and consume; their ‘real’ wages drop, even if their ‘nominal’ (numeric) wages remain the same. On the other hand, purchasing power increases for those who raise their prices ahead of inflation. Inflation also effectively redistributes purchasing power from creditors (lenders) to debtors (borrowers) via the ‘wealth effect’: money used to repay loans buys less after a period of inflation than when borrowed. But inflation, like competition and exchange, comprises a zero-sum game. As Lester Thurow pointed out: “For every loser there is a winner. Inflation can redistribute income, but it does not lower the total amount to be divided.”[283]

It has been claimed[284] that inflation has proportionally greater effects for high-income earners than for the poor; this follows, say claimants, because of reduced equity values, progressive tax rates, and other factors. If true, having to give up the Mercedes for a BMW should still involve less actual adversity than having to forgo a daily meal. But more importantly, the rich have more price-raising abilities than have the poor, as well as more money- and interest-making capacities, which can be used to compensate for inflation’s adverse effects.

Deflation also has its problems. A little deflation mightn’t hurt much, but when prices reduce significantly, as occurred in the Great Depression, business income falls, and inevitably unemployment results. In recent decades, though, deflation has occurred rarely, barely and briefly, so most of the discussion hereafter exclusively concerns inflation.

As for what causes inflation, one textbook admitted that “inflation is an area of economic theory and policy that is not yet well understood by economists.”[285] (Like so much else.) Balogh gave an essentially similar though more detailed answer: “A great many factors are involved, the interaction between them is intense, and their causal direction is difficult to discern. Cause and effect intermingle”.[286] Nonetheless, the economic orthodoxy has claimed the existence of two main causes and types of inflation.[287]

‘Demand-pull’ inflation occurs when excess demand ‘pulls’ up prices: if an economy’s aggregate demand for all goods and services increases without a corresponding increase in supply, then – as dictated by L$D – buyers will bid up prices. But because higher prices mean lower ‘real’ wages, producers tend to hire more employees, and this raises demand for labour, which allows the bidding up of wages, which discourages more hiring. With higher prices and wages, demand and consumption should then reduce for many reasons: the wealth effect; the so-called ‘money illusion effect’ (how people tend to neglect to increase spending in proportion to their raised income); because fixed tax brackets siphon off greater tax revenue from higher nominal incomes (‘bracket creep’); because government spending does not automatically keep up with inflation; because foreign buyers often find less inflated exporters; because local demand is likewise redirected to less inflated imports; and because higher prices prompt an increased turnover of money which increases its ‘transaction demand’ and, consequently, interest rates. For inflation to persist, with all these forces pushing demand down after prices and wages rise, something else must keep demand rising.