Chapter 6

Choices

“…we need to know not just what to rebel against but what to rebel for.” – Peter Cadogan[359]Thrashing about amid the turbulence of the economic flow has allowed us to accumulate, over the centuries, a great stock of ideas and inventions. And so, capitalism, despite its many faults, has left at least the developed world with a material standard of living beyond the wildest expectations of even a generation ago. Time now to move on before capitalism’s inherent contradictions and manic depressive obsessive-compulsiveness destroy all it has achieved. Time to retain and fully share the material success, and concentrate not on more of the same but instead on social, ecological and spiritual improvement. We can still enhance material success, but this goal must now take a back seat to more pressing urgencies.

To move on, it must be recognised that, despite their pervasive dominance, capitalism’s rules are not god-given, self-evident, unalterable commandments. They have become entrenched due to historical accident, so ingrained from long use that alternatives may evoke cognitive dissonance, but they remain arbitrary.

Perhaps many of us have grown too used to capitalism’s rules to consider changing, too habituated to recognise the addiction. But I am going to dream on. Instead of the profit-mad economic flow and its deranged rules, I will describe another more balanced, calmer, more controlled arrangement, one at our beck and call, with better rules more suited to modern times, needs and abilities, and more capable of providing a truly sustainable and attractive future.

Understanding the ideas that follow may not be easy because they will seem alien. So you’ll probably need to read it all at least twice, once to take in the parts separately, the second time to see the big picture to which they sum.

Although most of what follows details a new economic system, this chapter discusses democracy and why it also needs replacement with something that works properly. It may seem odd, given that the contents of part one almost exclusively concerned economic issues, that discussion of politics now precedes that of a revitalised economics – however, democracy as currently practiced would impede the economic proposals, whereas a properly working democracy will allow them to be used to their full potential.

6.1 Rule

“Here’s the modern political man, for sure he’s nobody’s fool,believes in media coverage as a promotional tool…

you’ve seen the TV commercials, you’ve seen the poster campaign

you’ve seen the ads in the papers, there’s nothing else to explain…

Politics now, it’s just like selling soap powder” – Peter Hammill[360]

The word democracy comes from two Greek words: demos, meaning people or population, and kratos, meaning power. So, democracy means people power – government by the people… at least in theory.

In practice, modern ‘democracy’ provides people not with the power to govern themselves, but with infrequent opportunities to choose between inadequate options of often poorly, selfishly, or otherwise unsuitably motivated, and mostly misrepresented, party devotees who, once elected, not so much serve the people as make decisions for them, usually in conjunction with influential financial supporters and lobbyists, and mostly regarding matters few if any of them properly understand, effectively ‘running’ society on everyone’s behalf (occasionally into the ground). These failings are aggravated by top-down hierarchical political and bureaucratic structures which encourage individuals to hoard information and communicate only what serves their interests. Democracy, as practiced, fails to live up to its name…

In particular, true democracy is thwarted by the kratos held by elected ‘representatives’, sufficient in amount to satisfy some of the less demanding Greek gods. But while some ‘representatives’ also speak as though gods, their utterances generally prove a lot less reliable. For it has come to pass that ‘representatives’ have said (more or less) “let there be no recession”, and, verily, a recession didst eventuate. One spake thus, “let no Australian child live in poverty by 1990”, and, lo, many children endured poverty that year and for years thereafter. Another bellowed “readeth mine lips – let there be no new taxes”, and, behold, new taxes didst appear.

The infrequent and inadequate opportunities for ‘the people’ to ‘choose’ their political ‘representatives’ are provided every few years by elections – at least for anyone old enough to vote, and if allowed. In most countries, women could not vote until the twentieth century: not until 1991 in Appenzell Inner-Rhoden, a Swiss canton; 1984 in Liechtenstein; 2005 in Kuwait; and 2015 in Saudi Arabia (the final laggard).[361] Black South Africans, despite majority status, did not gain voting rights until 1994. The USA’s African-American population could not vote until many decades after they were officially ‘emancipated’. Indigenous Australians were excluded until the 1960s.

Even so, not everyone takes the opportunity to vote at elections, because most nations do not make voting compulsory. For example, barely half of those eligible to vote did so in most recent USA Presidential elections (only 49 percent in 1996).[362] And yet, no matter how few vote or how close the voting, ‘representatives’ often claim the people have given them a mandate to govern.

One might think that political representation would involve ‘the people’ developing ideas and schemes for change, and presenting them to their ‘representatives’ to consider and arrange. Under existing forms of democracy, however, things work backwards. Elected ‘representatives’ fail to live up to their titles by making decisions for most matters – even the quantity of taxes needed for their wages, and for all other government spending – on behalf of the people, usually with little consultation (more often none). Even with referenda, often paraded as democracy in action, in most nations the people are merely presented with opportunities to authorise or reject proposals of their ‘representatives’ (often concerning complex issues but expressed as simple yes-or-no proposals).[363] So democracy as practiced yields not representation, but merely government.

The aspiration of people power is further degraded by how elections effectively grant ‘representatives’ multi-year employment contracts, which can only be broken by extremely gross negligence or law-breaking, not mere incompetence or dissatisfaction by voters. Ironically, the goal of greater labour flexibility, however loudly advocated by ‘representatives’, does not extend to them. Yet democracy as practiced has more shortcomings than just this.

The task of deciding who to vote for is greatly simplified – overly so – by political parties: these offer a ‘team’ of election candidates, allegedly if not actually in agreement on principles and policies for governing. Hence, voting for a party candidate acts as a vote for his/her party, its views or ‘platform’, and its leader and senior ranks. Voters need make much less effort to learn and assess well-publicised party creeds than the many and diverse platforms of independent candidates, so not surprisingly political parties usually gain far more votes. However, party platforms commonly conceal widespread differences of opinion between factions within each party, and oversimplify political reality – as a result, once elected, pragmatism often causes party principles to be abandoned and election ‘promises’ to be broken.

Simplifying the oversimplified even further, many democracies are dominated by only two political parties – often barely distinguishable except to their most rabid or habituated supporters – which attract the vast majority of votes. Such democracies might be called ‘poligopolies’.

Political parties not only simplify the task for voters, but also for candidates, especially by providing them with greater financial resources than most could acquire on their own. And money is certainly needed for election campaigns – for publicity and promotion, to pay for costs of transport from one corner of the electorate or nation to another, to make predictably inane speeches and hold quasi-religious rallies, to plaster flattering posters on billboards and walls, to run advertisements in the media, even (in many places) to cover charges for candidate registration. Elections now cost literally fortunes – millions of dollars, even hundreds of millions for some recent USA Presidential candidates.[364]

But the sizeable memberships and loyal supporters of political parties can provide only some of the money needed by party candidates. In some nations, part of the rest is publicly funded from tax revenue. But most of the remainder comes from donations, inevitably by those who see advantage in the policies being promoted by candidates and their parties. Obviously, the wealthiest corporations and individuals not only have the most incentive to donate but can most easily afford such an investment (often tax deductible). Likewise, they are most disposed to invest in lobbying governments during their terms for favourable policies.

The wealthy who control large firms, multinationals, and especially the media, can give candidates and elected politicians even more than financial support however. Publicity and promotion, or suppression and criticism, biased reporting and editorials, and daily restatements of preferred poll ‘results’ can all be arranged with particular ease when business ownership concentrates to the current extreme. Enter the L$D-competitive pursuit of self-interest, exit any hope of democracy.

So, as a natural and unavoidable side effect of leaving all to pursue self-interest, mutually masturbating coalitions of political and economic forces constantly shift and realign as they overtly and covertly tussle for control. But although the elected and the elect may swap or share puppet and puppet-master roles as circumstances change and interests overlap or diverge, the concentration of so much power in so few hands invalidates the ‘one person, one vote’ claim (or assumption) of democracy. As Ralph Miliband put it: “Political equality, save in formal terms, is impossible in the conditions of advanced capitalism. Economic life cannot be separated from political life. Unequal economic power, on the scale and of the kind encountered in advanced capitalist societies, inherently produces political inequality, on a more or less commensurate scale, whatever the constitution may say.”[365]

The flaws of modern democracy are further compounded by the inadequacy of democratic choice. The majority of election candidates, still mostly male, come from business and law; many, especially USA presidents, also own great personal fortunes; few could be called young. To put it in the most polite terms possible, rich old/middle-aged male businesspeople and lawyers have no monopoly on the skills and talents required for governing (or even, if they were so disposed, for knowing how to assess the desires of the people and arrange change accordingly).

Furthermore, ‘representatives’ are not required to possess any relevant qualifications or skills other than popularity – with other party members in order to win their nomination to stand for election, and with voters. Of course, popularity need not bestow aptitude. Indeed, popularity can thwart both government and representation – by reinforcing belief in personal or party dogma, by bloating egos, and by rendering the masses more willing to abdicate control and less thoughtful about the consequences.

Attempts to gain popularity also cause problems. For the public to be able to assess an individual’s potential as a political representative, or a party’s as a government, they need information. What they instead receive generally misinforms with greater intensity even than the often irrelevant credos of party platforms. Politicians want your vote, and this motivates them to inform you only of what they expect you to find positive about them.

Generally, it serves the purposes of candidates and politicians to act full of conviction and confidence in their platform and their own capabilities, whether they feel it or not. It serves them to appear as though they can answer all questions, but many answers can lose votes; so they evade questions (especially those not understood) while trying not to appear evasive. This can be done by sly changes of subject, appeals to patriotism and prejudice, thalamic slander of opponents, reiteration of principles and viewpoints so as to imply rather than spell out answers, forceful proclamations of identifying and distracting catch-cries (such as ‘that is nonsense’), and numerous other verbal tricks and deceptions.

Like others intent on spreading conviction, politicians rely heavily on emotional language that prevents an accurate communication of facts and issues. For instance, political orators tend to refer to the obstinacy of opponents as ‘pig-headedness’, but that of themselves or their colleagues as ‘firmness’; thus people who share a common trait are described with different words having clearly associated emotional qualities that condemn foes, but exonerate and applaud friends. Such an approach communicates not information, but personal bias.

Politicians bandy about many words and phrases that provoke emotional reactions – like ‘democracy’, ‘freedom’, ‘national welfare’, ‘liberty, equality and fraternity’. Such terms imply unquestionable ideals shared by listener and speaker alike, and so help to avoid questions about what is actually meant by them. But words remain one thing, and actions another. Election speeches full of the word ‘freedom’ are often followed up by new legislation restricting liberties and civil rights; major parties with self-proclaimed ‘green’ credentials buy the environmentalist vote, then offer excuses for not reducing mining and/or timber-logging in national parks. Election promises, as any lip-reader can confirm, are often not kept.

Most politicians know that the ‘right’ words can work people up into enthusiastic states where they tend to hear what they want to hear – especially when helped by the group hysteria of public rallies and meetings, stirring and patriotic music, half a lifetime’s habits of thought, and the false prestige of famous orators (“he’s been in power for years now, he must know something”). But the ‘right’ words often so camouflage political intentions and motivations, they render electioneering comparable to dishonest advertising – especially now when media consultants and advertising firms help market and sell political ideology in much the same way as they do any other commodity.

Commercial advertising reduces most of the task of representation – as well as the many diverse and often unresolvable issues of the day – into simplistic slogans, propagandistic sound-bites, and almost subliminal imagery. Advertisers use selective and often misleading information to display opponents as inept or dangerous, and to cast clients as virtue-ridden saints. Simple but powerful images that create feelings of fear or faith highlight the supposed differences between political foes, associate ideology with ‘family values’ or a threat to national well-being, justify failure and rebuke success. With all the techniques available to manipulate image and sound, rhetoric and bombast are presented as factual and informative. Entire platforms are reduced to catchy jingles and empty trite slogans such as ‘the brighter future’, ‘it’s time’, or ‘the sensible choice’. Mantras to avoid enlightenment.

Whether to win an election or to make a point afterwards, the fatal combination of entertainment-focussed media reporting and political advertising gives people not a display of substance or aptitude, but skilfully orchestrated and often false representations of image and charisma. Media consultants fashion and refashion candidates for the camera: they arrange more ‘authoritative’ styles of hair, suit or skirt; adjust the pace or delivery of speech; fuss over pronunciation, diction, and deportment; regulate eye-contact and body language; turn wimps into winners. Televised debates are won or lost not on the quality of argument, but on candidates’ five o’clock shadows, height differences, and perspiration rates. Conceivably, many revered past leaders might never have been elected had current practices been used in their time. Lincoln’s facial warts and ‘crazy’ wife, Churchill’s and Menzies’ girth, and FDR’s polio-weakened legs, all might have seemed to marketers as possibly irremediable electoral liabilities.

Theodore Roszak suggested that political campaigning has, over time, grown “more and more obsessively focused on… the huckstering skills of the marketplace”.[366] This can be seen further by how political parties and governments now rely on polling – the ‘establishment’ of public opinion – so that campaigning and government, in their own misleading fashion, can be seen to be concentrated upon what ‘the people’ are claimed to regard as issues, and so that policies can be seen to provide what is supposedly wanted.

Polling, however, can mislead as much or more than advertising because questions can be phrased and ordered so as to attract the desired answers. For instance, pollsters would have a better chance of ‘finding’ that people favour expanding their nation’s nuclear arsenal, if they asked: (1) Are there any nations that threaten or might one day threaten our nation’s security? (2) Should we have the most powerful deterrent available for self-protection? (3) Should we increase nuclear weapon production? On the other hand, the opposite opinion could be all but guaranteed with a single question: should we sacrifice other government spending, on such things as schools and hospitals, in order to build more bombs, remembering that already enough nuclear firepower exists to destroy the world several times over? Because the style of question influences ‘the’ answer, parading poll results as public opinion can misinterpret and misrepresent belief, and so stymie rather than assist political choice.

Uniformity of opinion will rarely be found by pollsters or anyone else. Similarly, democracy, as currently practiced, must fail in its attempts to apply a one-size-fits-all approach. Political parties fraught with internal bickering, squabbling coalitions elected with bare majority support, neighbouring electorates with diametrically opposed voting patterns, all belie the claim of mandates or consensus. Instead, any democracy truly living up to its name must reflect the clear and obvious plurality of views among its population. To that end, a completely reorganised form of participatory democracy needs to be constructed…

6.2 Self-determination

“The notion of the majority is used as a dogma by political leaders to prevent democracy… We are sold the idea that voting is action whereas a moment’s reflection will show that voting is abdication. When people take government into their own hands that is democracy, when they relinquish it, leaving it in the hands of MPs and Councillors, that is something else – mere representative government. We have been tricked into supposing that the two things are one when in fact they are mutually exclusive.” – Peter Cadogan[367]Aiming for a much more direct and participatory form of democracy, Peter Cadogan once suggested that: “The way ahead lies through… sovereign city regions supported by national self-financing utilities, industry, commerce and the professions.”[368] Cadogan identified the pluralist nature of such a system when he pointed out that “each region, being sovereign, will take decisions peculiar to itself.”[369] This envisaged “direct democracy” depends on “face-to-face accountability… transformation of local government (made feasible by manageable scale and communications)… and… the division of political labour so that all who are willing and able to take on some social responsibility are able to do so”.[370] As to agreement, Cadogan wrote: “The important numerical question, constitutionally, is not the majority at all. It concerns the number of people effectively engaged in decision-making.”[371]

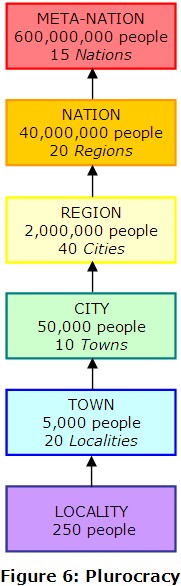

Cadogan’s ideas have something in common with a more daring notion outlined in an episode of the British TV satire ‘Yes Prime Minister’.[372] Extending both sets of ideas, and augmenting them with others, yields plurocracy – a bottom-up, pluralist, decentralised and participatory version of democracy underpinned by small self-governing electorates arranged into progressively larger associations whose decisions require the majority agreement of constituent groups…

The

essence of plurocracy lies in its bottom-up structure, based on small

electorates called localities, each consisting of

(say) 250 people

(perhaps 200 old enough to vote). Groups of (say) twenty localities

form larger

electorates (of 5,000 people) called towns. Groups

of towns, in turn,

form still larger electorates – groups of these, yet larger

electorates – and

so on, with the biggest varying in size to suit population densities,

ethnic

and religious groupings, national or state boundaries, and other

factors. To

illustrate the idea (as in Figure 6), ten towns might form a city

(50,000 people), forty cities might form a region

(2,000,000); twenty

regions, a nation (40,000,000); fifteen nations, a meta-nation

(600,000,000); and twelve meta-nations, the world. Something like that.

The

essence of plurocracy lies in its bottom-up structure, based on small

electorates called localities, each consisting of

(say) 250 people

(perhaps 200 old enough to vote). Groups of (say) twenty localities

form larger

electorates (of 5,000 people) called towns. Groups

of towns, in turn,

form still larger electorates – groups of these, yet larger

electorates – and

so on, with the biggest varying in size to suit population densities,

ethnic

and religious groupings, national or state boundaries, and other

factors. To

illustrate the idea (as in Figure 6), ten towns might form a city

(50,000 people), forty cities might form a region

(2,000,000); twenty

regions, a nation (40,000,000); fifteen nations, a meta-nation

(600,000,000); and twelve meta-nations, the world. Something like that.

With plurocracy, decisions are not abdicated to representatives (who nevertheless have roles to play, as the next section explains), but made by the people themselves – for any and all issues with which they wish to be involved. The people make decisions from the bottom up: for any electorate to plurocratically pass any proposal requires approval not only by a majority of its voters but also by a majority of its constituent electorates – each, in turn, approved also by a majority of their constituent electorates – all the way down to the locality level.

Plurocratic electorates (‘plurocracies’) at every level function semi-autonomously. Although each locality, for example, must heed the plurocratic decisions of its town, these apply only to issues affecting two or more localities, as agreed upon plurocratically. Each locality makes its own rulings, for purely internal affairs. So, the decision to build a new house or shop, for instance, is made by the locality it is to be built in (perhaps recommended by its town or city); but a height restriction, an ecologically safe and efficient method for its construction, and/or other relevant matters, might be agreed upon at the town or higher levels (following plurocratic agreement of that level’s constituent electorates).

This approach follows that of a suggestion by David Weston (in regard to community-based and -issued currency): “the priority for decision-making and action-taking should be at the most decentralised level possible. Only when those decisions and actions impinge upon the well-being of the next-larger communities or regions, should those too have an influence.”[373] More or less the reverse of what happens now.

Just as importantly, each plurocratic electorate has the right to secede from its ‘parent’ electorate. If, for example, a locality found itself often voting against decisions plurocratically passed by its town, and felt enough dissent, it might choose to secede from its town, and join other more-like-minded localities (not necessarily with common borders) or else become independent. This option, although no guarantee, should help protect minority groups.

The autonomy of each plurocratic electorate is restricted only by their members’ imaginations (and by the time they have available to utilise them, which the next chapter explains should greatly exceed what most people have now). Not only does each plurocracy make up its own mind, it even chooses how it makes up its own mind. Individual plurocracies can settle on their own definitions of ‘majority approval’ or vary it according to the issue. Some might ‘weight’ votes in certain circumstances, so people most affected by decisions have the greatest say. Others might vote on a scale of (say) zero to a hundred, with a pre-agreed average or median score required for any decision to be passed. Still others – especially at the locality level, for which it is most suited – might seek consensus for some or all issues, by modifying proposals until they satisfy all who previously dissented.

Something akin to plurocracy (though not as multi-layered, flexible or as feature-laden) is already in use, and operates highly successfully.[374] Switzerland consists of a “confederation of [26] self-governing cantons, each of which can leave the confederation if it so wishes… [C]itizens of a single canton can divide themselves into two cantons if they are, as they have been, so minded… [T]he governing systems, the boundaries and the allocation of constitutional powers and prerogatives have been decided by the people themselves”.[375] The system is underpinned by semi-autonomous “rural Swiss commune[s] at the village level, each with a couple of thousand inhabitants[, which]… have their own constitutions”.[376] Also, referenda can be initiated at the communal, cantonal, and federal levels, if enough signatures are collected – 100,000 or less depending on the issue.[377] Minorities are protected by communal and cantonal semi-autonomy, the right to secede, and the requirement that federal referenda can only be passed if a majority of cantons vote for them.

It might be thought that a nation comprised of various ancestries, about equal parts Protestants and Catholics, and with four main languages, might have experienced territorial disputes, religious feuds, even ethnic cleansing. Instead, Switzerland's decentralised participatory democracy – and undoubtedly other important factors – have encouraged a stable co-existence of diverse views, leading to enduring peace and prosperity.

Plurocracy, however, decentralises political power further than in Switzerland. It enables decisions to be made from the bottom up, but still allows information to transmit up, down, and across each level to form the network essential for a true democracy. It fosters economic self-management similar to that envisaged by Ted Trainer and James Robertson,[378] in which individuals and households engage in do-it-yourself community projects at the locality level, with town, city and regional planning ‘above’ them, augmented by national, meta-national and global co-operative agreements.

Of course, even with the bottom-up decentralised structure of plurocracy, some functions of its higher levels – especially those involving relevant specialists, planners, advisors, and other ‘experts’ – probably need to be centralised to some extent. As Gabel put it: “There are certain things that make sense – with present day needs, technology, resources, and know-how – to do on a large centralized/integrated scale; others make sense on a decentralized scale. Which is which is subject to steady transformation.”[379] Determination of which is which can be left to decentralised plurocratic choice, informed by ‘expert’ opinion. Nevertheless, efficient allocation of most resources and responsibilities can be made more likely if the suggested sizes of towns and cities are adopted…

Much research[380] indicates that the most cohesive self-sufficient communities consist of about five to ten thousand people (a plurocratic town or two): this size ensures the lowest possible cost per person for the satisfaction of most social and many cultural needs, maintenance of eco-energy systems, and provision of some services such as basic health-care, all of which the communities themselves can run and plan (rather than distant bureaucratic government departments). Groups of fifty to a hundred thousand people (a plurocratic city or two) likewise can control, operate, and, at the lowest possible cost per person, provide themselves with housing, education, sanitation, energy, entertainment, libraries, information, law enforcement, street maintenance, fire protection, parks and recreational facilities, most healthcare, and many other services. (Of course, the resources and skills of larger groupings such as regions and nations need to be pooled for some purposes, such as high standard orchestras, sports teams, universities, specialist research groups, and other ensembles of note.)

6.3 Representation

“…the only real ‘seizure of power’ by the ‘masses’ is the dissolution of power” – Murray Bookchin[381]As mentioned, plurocracy involves electoral representatives, but they have very different roles than those currently the norm for democracy.

With plurocracy, voters of each locality elect one person from among themselves to act as their representative – or, if they so choose, select different representatives for different issues, or roster the job among volunteers, or settle on representation in whatever manner they determine. Whatever the method used, representation is not faceless or unaccountable in an electorate of two hundred voters. Indeed, most people could end up becoming personally acquainted, perhaps friendly, with their representative, even in geographically larger rural localities.

Similarly, each town selects their representative from their constituent localities’ representatives – or maybe the localities’ representatives make the choice, with town reps perhaps replaced or assisted at the locality level. Likewise for higher levels. Importantly, decisions on these matters are determined independently by each electorate.

And so, ‘government’ at any level consists of all the elected representatives of that level, not simply those able to form a majority based on their affiliations with political parties. Indeed, given the bottom-up process of plurocratic decision-making, political parties seem more likely to impede true independent representation than assist it, and so might be best avoided.

With or without political parties, much less complacent representation than occurs now can be further encouraged by storing the votes for all levels’ representatives online, each vote accessible to its owner to change any time he or she wishes. This not only saves the cost and tedium of periodic elections, but also enables voters to instantly dismiss poorly performing representatives, which should spur them on to avoid such a fate.

Some might consider a permanent electronic election liable to lead to instability, due to rapid changes in representation. Italy could be cited as an example of where instability results from power changing hands too often. However, with plurocracy, a change of representation only corresponds to the people’s change of mind, not to a potentially destabilising power shift. Power remains with the people – especially because of the nature of plurocratic representation…

Plurocratic representatives have mostly coordinative roles, providing or disseminating information, options and proposals to their electorates, making sure they have all available and necessary information to make up their minds, and communicating to other electorates the majority opinions of those they represent. Though some, as now, might hope to pretend otherwise, no representative can know everything – so, on occasions, they will need to seek information, options and proposals from various ‘experts’. But even then, the people make the final decisions as to which ‘expert’ advice to follow.

To assist representatives and their electorates, the online voting system is also used, by any voter who wishes to use it, to register an opinion on any issue requiring a decision; to seek, publicise, obtain and assess ‘expert’ advice; to bring any issue to the attention of those it affects; to initiate and arrange referenda; to allow any vote on any decision to be reviewed and altered as voters plurocratically change their minds; and to generally function as an electronic communal noticeboard. True democracy from the comfort of your favourite armchair (although face-to-face meetings also occur, at least at the locality level).

Self-government comprises the essential nature of plurocracy: people proposing, deciding, and implementing their own schemes whenever possible, advised by ‘experts’ when unavoidable, and coordinated by each level’s representatives directly answerable to their electors.

To an extent, the very notion of government vanishes if people govern themselves: with plurocratic representation, no meaningful distinction exists between the governed and the government, between private and public sectors. Groups take on responsibilities for tasks now associated with government (such as law and defence), and undoubtedly initiate most ideas for improving how they fulfil their duties, but they ultimately serve the plurocratic will of the people, and always remain answerable to them.

Many readers, comparing plurocracy with today’s hierarchical democracies in which governments make and implement most decisions usually without consulting voters, might fear that plurocratic decision-making, especially if involving consensus, would slow down the wheel of progress, if not grind it to a halt. Of course, plurocracy might well take longer to decide what needs doing – but decisions will more accurately represent what people want. So, with sovereignty over themselves, and a more cohesive and integrative political structure, perhaps people will make a less fast wheel, but for most it will seem a better wheel.

Some readers might also question whether people can be trusted with the power provided by plurocracy, but I consider such a question to be misguided. History’s numerous examples of centralised non-participatory empires – from ancient Rome to the Soviet Union – all of which over-extended themselves and/or collapsed under their own weight,[382] demonstrates that major problems are created by concentration of power, not the sharing of it.

Still, the considerable novelty of plurocratic power-sharing certainly requires care and responsibility. On this subject, I have considerable optimism. Ask any parent: a child only learns responsibility when they are given it. Similarly, adults won’t learn political responsibility until they are given it…

6.4 Rights & Duties

“Our present commercial ‘civilization’ can be characterized as of an infantile type… The rules and regulations are naturally antiquated, and belong to the period to which the underlying metaphysics and language belong. The ‘adult’ or scientific semantic stage of civilization would be precisely the ‘social’ stage of complete evaluation of our privileges and duties.” – Alfred Korzybski[383]In one of Doris Lessing’s science-fiction novels, an alien civilisation is depicted in which: “There was no written or formal constitution… [S]ome of the worst tyrannies… had ‘constitutions’ and written laws with no purpose except to deceive the unfortunate victims and outside observers. There was no point in constitutions and frameworks of laws. If each child was taught what its inheritance was, both of rights due from it and to it, taught to watch its own behaviour and that of others, told that the proper and healthy functioning of this wonderful city depended only on his or her vigilance – then law would thrive and renew itself. But the moment any child was left excluded from a full and feeling participation in the governance of its city, then she or he must become a threat and soon there would be decay and then a pulling down and a destruction.”[384]

Just as Lessing’s imaginary civilisation depends on vigilance, integrity and participation, so does plurocracy. For example, plurocracy, on its own, can encourage but not guarantee an end to discrimination and persecution of minorities. In the absence of sufficient understanding and empathy, plurocracy could instead result in a series of voluntary residential relocations and/or secessions leading to independent electorates composed almost entirely of minorities – a very parochial form of plurocracy. To avoid this, for plurocracy to foster a peaceful co-existence of diverse groups, people must participate with vigilance, and be educated from as early an age as possible to understand the responsibilities associated with self-determination.

To this end, I propose not a series of complex legal frameworks or a bill of rights or a constitution (though at least some of these might have their uses), but a simple overarching guideline: everyone has a right to do as they see fit, as long as their choices fulfil the duty not to harm others in the process.

Of course, no guideline is foolproof.

Even with such a guideline, care is required to distinguish the truly harmful from the merely disagreeable – to avoid misinterpreting due to shocked sensibilities or outraged ‘morality’ (or laziness) or other reactions based on personal matters of taste and disposition. It does not suffice either to rely on a formal majority definition of ‘harm’, because this opens the door to just the sort of rule by weight of numbers that persecution depends upon – hence, localities (at least) should probably pursue consensus rather than majority approval. The guideline indeed can only guide – it cannot resolve disputes on its own, nor replace the need for thought and consideration.

And so, I believe the conclusion cannot be escaped: because agreement, however reached, nearly always avoids unanimity – because, ultimately, we can only agree if we agree to make efforts to agree – we cannot be made to behave fairly, responsibly and properly; we can be educated to our responsibilities and rights, but even then we can only trust each other to act fairly and appropriately; we can settle on freedom of informed and dutiful choice as our ultimate right, and vigilance and participation as our ultimate duties, but because these remain only generalised ideals, no system can be made to function fairly – it can only be carefully and suitably designed, then trusted to work. Giving people the ability to plurocratically choose will not work unless people are trusted to choose carefully.

Sorry, but no absolute solutions exist, no hard and fast realities. Each moment involves choice and chance. Control is not possible, only trust. And care. And forgiveness and understanding when mistakes are made.

We probably have no way forward except to learn to trust each other, and to learn to tolerate each other’s differences. Enclaves of people with different views, habits, and cultures will always exist, and we will always retain the onus not to let it matter. Plurocracy cannot guarantee the best outcomes, but it encourages them far more than do current forms of democracy.

Trust and tolerance can be encouraged in many other ways, too – not just by education but also economically. If accompanied by a competitive dog-eat-dog economic system, which inevitably breeds distrust, plurocracy would function less well. But a co-operative economic system might provide enough material security for all to motivate us to learn to trust each other and to tolerate each other’s differences – especially if it unleashes us from the afflictions of nine-to-five humdrum, and so gives us ample spare time to properly deliberate over decisions, to seek and assess information, and to use our plurocratic abilities for change creatively and responsibly. To properly explore the potential of plurocracy, its accompanying economic system must be detailed…

Part 2 Part 2 |

Chapter 7 |