Chapter 7

Needs & Wants

“…there is nothing natural about buying and selling things for profit, and allowing markets to determine their value.” – Raj Patel[385]With or without plurocracy, to properly make responsible decisions about any activity or subject, its ‘worth’ or harmfulness needs to be thoroughly established. This requires an unbiased approach, unfettered by thoughts of self-interest, and able to take into account not just people directly effected but those indirectly concerned, including future generations. Any activity’s effects on its encompassing ecosystem also needs consideration, else sustainable development remains just a convenient but insincere phrase.

Plurocracy’s decentralisation of decision-making helps to achieve these aims by enabling local control, thus making it harder for privileged elites to pursue their self-interest at others’ and the environment’s expense. However, as long as capitalism’s unholy trinity of profits, jobs and growth continue to be treated as the real issues and motivations, even decentralised plurocracy cannot compensate for such false decision-making criteria.

Of the three members of the unholy trinity, only jobs cannot be avoided. Perhaps in the far future, a life of complete leisure can be attained for all, with labour performed only by machinery, but I doubt it. For the immediate future, though, we will certainly have to continue working, at least to some extent.

Profit and compelled economic growth on the other hand are not essential, merely habitual. Yet one without the other cannot work: as chapter 1 explained, the two are interlinked, with growth requiring and sustaining profits, and profits encouraging and needing growth. So, to avoid the compulsion to grow, profits must be abandoned.

A few economic ‘heretics’ advocate a no-growth or ‘steady-state’ economy, but this cannot be achieved if profit, or interest, is involved, because (as per section 1.5) they make losses inevitable, thus giving any economy that includes them a tendency to contract. Even if an economy did for a while achieve a steady-state (without suffering reduced employment), profit-maximisation would still encourage greater productivity which would lead to less money distributed as wages to afford the same amount of or more output, which would cause economic contraction. Thus, profit, interest and L$D-competition all guarantee very unsteady steady-states.[386]

Without profit and interest, however, growth is not compelled, and so a steady-state economy then becomes possible.

Certainly profit and interest have little compatibility with plurocracy: if some must lose for others to gain, wealth cannot be properly shared, and the level of trust necessary for plurocracy to function optimally cannot be expected to be achieved.

So, sound reasons exist to design economic rules free of the constraints and costs of profit and interest…

7.1 Cost And Price Equalisation

“The cash flowing into an organisation must be kept in balance with the cash flowing out, and procedures are required for distributing the outgoing cash flows fairly among all concerned. Accept that convention and you have the conceptual basis for a post-capitalist and post-socialist society.” – James Robertson[387]To a large extent, we’ve been doing it backwards, horses dragged behind runaway carts. Our current economic rules compel us to spend ever more – actions and decisions are then made subject to that compulsion, with much harm and inefficiency resulting. We don’t need this. We also don’t need ever more of the same as techno-optimists hope. And we certainly don’t want the disasters of insufficiency envisioned by doomsayers. Yet we do not have a choice only between ever more and dangerously less. Rather, we need to find a balance, and settle for enough. But that can’t be done while being driven by an economic engine without an off-switch.

So, we need to construct new economic rules that allow us to organise and ensure enough, yet able to cope with fluctuations above or below expectations or ideals (rather than falling in a heap each time we don’t spend ever more). We need rules that don’t compel ever more activity, but which ensure that only work of genuine need or sufficient desirability is paid for, that all such work can be afforded, and that no-one is penalised whenever less (or more) work is needed.

The basis of suitable new economic rules follows from a simple observation: if jobs are lost as productivity increases, then total income obviously reduces – but so too does total costs. This can be used to great advantage if profit, interest and L$D-competition are not involved, as will now be demonstrated.

Consider an economy of any size over (say) a week during which, for the sake of explanation, it’s expected to neither grow nor contract: production won’t change, and everyone keeps their jobs and consumes as normal. Production costs for such a stable economy over the week are known in advance: without interest or profit, total producer costs equal total wage costs (either paid directly to the producers’ employees, or indirectly to those of other producers, as Figure 1 demonstrated). Hence, without profit or interest, the total prices of the goods produced over the week can be set to equal the total production costs.

Of course, expectations are not always met. So, at the end of the week, it makes sense to examine what actually happened, what work was really required, especially the time needed to do it. If less work was needed by some producers than anticipated and paid for over the week, then average working hours for the entire economy can be reduced accordingly for the next week, with the necessary work shared. But if the total costs of work reduce, so too can the total prices of the goods produced by that work – by the same proportion. An example will hopefully make this clearer…

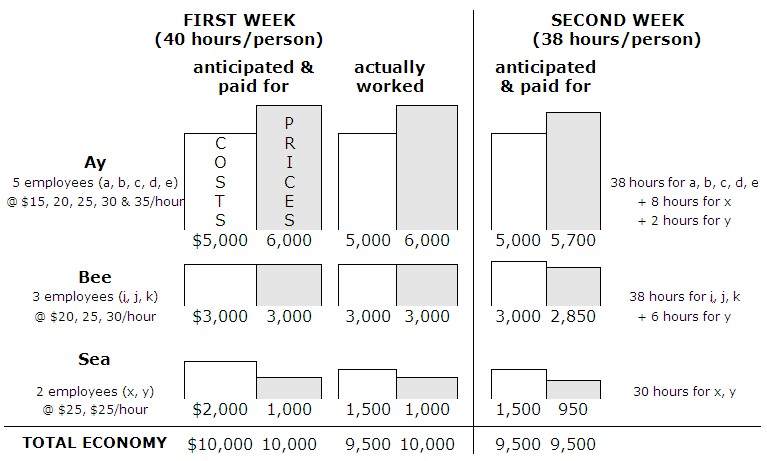

Consider a simplified economy, depicted in Figure 7, consisting of three businesses – ‘Ay’, ‘Bee’, and ‘Sea’ – each having a forty-hour working week. Between them, the businesses have a total of ten employees paid at the rates indicated in the diagram, so that an anticipated total of four hundred man-hours for the week involves a total expenditure of $10,000. The total costs are balanced by the total prices: both $10,000. However, the prices of individual products need not equal their costs of production: individual businesses can have total costs different to their total of prices as long as prices in aggregate for all businesses equal their aggregate costs. (Section 7.5 explains the considerable advantages of having different prices than costs for some products.) Hence, in the diagram below, Ay’s prices exceed its costs by the same $1,000 amount that Sea’s prices fall short of its costs, while Bee’s prices equal its costs, as do those of the total economy.

Figure 7: Cost And Price Equalisation

Now say Sea’s two employees find ways to perform their required work with ten hours less labour each over the week, and they expect to maintain this saving in the future. So, only 380 man-hours – ninety-five percent of the first week’s anticipated work – are actually required to produce the same output. Therefore, in the second week, all the necessary work can be shared over a 38 hour week in the manner depicted in the diagram, with prices likewise reduced to ninety-five percent of those set during the first week. In this way, Sea’s savings prompt everyone to work five percent less, and so earn five percent less – but because this also reduces the economy’s total costs by five percent it allows all prices to be reduced by five percent. Thus, purchasing power is kept constant for all, while avoiding unemployment and recession.

This approach – ‘Cost And Price Equalisation’ (CAPE) – has the main effect of absorbing changes which now give rise to the boom-bust business cycle into altered working hours and prices. If efficiency improvements and/or sales declines and/or reduced consumption and/or anything else decreases the need for work by x percent, the same work is shared over a working week also lowered by x percent. Income and total costs then also reduce by x percent, because of which CAPE requires an x percent reduction of all prices. Similarly, more shared work, whether because of reduced productivity, natural disaster, or any other reason, causes the working week, income and prices to all rise by the same proportion – a much better alternative than the inflation that normally results under capitalism.

So, though people can get less (or more) income, none lose (or gain) purchasing power because all prices drop (or rise) by the same proportion as income. And if prices and income move up or down in unison, then growth or contraction or a steady-state can be handled by sharing the work around. (As mentioned, despite plurocratic decentralisation, some functions can be most efficiently pursued with centralised approaches: if all prices of all businesses are recorded on a single database, all of them can be easily altered periodically by the same CAPE proportion using a simple computer program.)

This provides the basic overview but the devil as always is in the detail – especially concerning the sharing of work. However, other proposals to be detailed in subsequent sections ensure that these details merely complicate rather than undermine CAPE, and so the details are discussed in the final section of this chapter.

Make no mistake though: this is not capitalism. It has no profits, maximised or otherwise, or interest, nor does it encourage ruthless labour market competition. Likewise, businesses whose prices adjust in line with changes to the overall economy cannot be regarded as capitalist. But neither does this approach retain the faults of capitalism, because it neither requires growth nor leads to inevitable loss.

Habituated self-serving capitalist dogma aside, a reduction in the work required to produce and distribute needs and desires should be treated as welcome. Rather than increased productivity and/or sales declines and/or reduced consumption leading, as now, to job losses, they can instead prompt necessary work to be redistributed among all people wanting and able to work so that the average time spent working reduces – CAPE allows this to happen with the resultant reduced costs for producers balanced by a lowering of prices, so that reduced working hours involve no loss of purchasing power.

CAPE removes one of capitalism’s most fundamental motivations, to preserve and create jobs. It unleashes us to instead reduce work, to levels now only in our dreams…

7.2 Saving Work

“…unemployment due to our discovery of means of economising the use of labour [is] outrunning the pace at which we can find new uses for labour. But this is only a temporary phase of maladjustment. All this means in the long run that mankind is solving its economic problem.” – John Maynard Keynes[388]To unleash CAPE’s (and our) full potential, work planned for any period is paid for even if not all of the hours expected prove necessary ie. for any CAPE period, workers are paid for the hours expected to be needed from them, even if they find ways to increase their productivity so that they actually work fewer hours. Then, not only are people prevented from being financially penalised for finding ways to save themselves – and ultimately their community – work, but also a clear incentive of fewer working hours motivates the saving of labour.

Indeed, in this way CAPE allows work to be not merely reduced but minimised.

We could work a lot less than we do now if we abandoned all the unproductive work currently performed, automated everything we could of what remained, and shared the rest – especially if we also built to last instead of to obsolesce, and if we produced and consumed less slavishly and more responsibly (particularly by minimising or avoiding pollution, resource-hungry processes, and non-renewable energy use). After considering these matters, Trainer concluded that “it is quite plausible that our non-renewable resource use and the time we would have to spend on commercial production could be slashed to the region of one-fifth or less of their present values.”[389] A one-day working week.

Supporting Trainer’s claim, similar results follow by using Fuller’s estimate of unproductive work (mentioned in section 5.1). If we need to do only thirty percent of the ‘work’ that currently occupies about ninety percent of those who want employment, each for about forty hours a week, sharing it equally requires a working week of less than eleven hours. But the less we work, the less resources we need, like petrol, car and truck tyres, steel, concrete, paper, and energy; and the less damage we cause and need to fix, such as through pollution, congestion and waste. So, less work further reduces the need to work (in economic parlance, a ‘negative multiplier effect’), making a one-day, or even a half-day, working week more than plausible.

However, this possibility can be taken even further. Some work likely to always be needed or wanted nevertheless does not have to be paid for in a plurocratic CAPE-based economy. A shorter working week unleashes time to take on personal unpaid responsibilities for tasks people now pay for because of insufficient spare time, such as house chores, and at least some aged, child and disability care. A shorter working week also gives individuals, neighbourhoods and local communities the time to take direct responsibility for even some social work, basic nursing, and much else of the human, health and other services now run by governments or businesses. A shorter working week even encourages those in the so-called entertainment, sports, arts, recreation, sex and other ‘industries’ to do at least some of their ‘work’ for pleasure instead of for money. All of which allows the working week to reduce further.

On the other hand, we must also consider whether some work that isn’t now done really needs to be, and whether current efficiencies can be maintained as more of the developing world demand a share of limited fossil fuels and other natural resources. In the short term, these concerns might negate at least some of the potential for shedding unnecessary work, but in the medium term of perhaps a decade or so, as we learn to produce and consume more sensibly and responsibly, and do only work that is really needed and wanted, we might well end up with a one-day working week.

Common-sense dictates only that hours worked equal the minimum necessary to perform the work really needed and wanted – taking into account all work. Hence, if, say, ten hours of labour are saved by using a certain piece of technology, but eleven hours are then needed to clean up the mess resulting from that use, then it involves less work overall not to use that technology. (This approach has been called ‘least-cost planning’, and I will return to it in section 8.4.)

Not everyone need work the same hours. Because individual consumers and producers have different needs and wants, working hours can vary from place to place and time to time, though the average responsible citizen should aim to work, over their lifetime, an average total amount. Thus, those whose work cannot easily be performed in a single day per week can work longer hours but (hopefully) over shorter working lifetimes. An economy might have so few doctors, for example, that each needs to work (say) five days a week, until more are trained to ease their burden and allow them to return to standard hours – but then their extra initial contributions would be compensated by subsequent reduced hours and/or earlier retirements. This complicates CAPE, but given sufficient computer resources and organisation, it almost certainly poses far less trouble than what now goes into calculating GDP.

CAPE need not be applied with unerring exactitude in any case. Nothing useful is gained by calculating requirements and capacities to a level of precision that leads to a working week of (say) 33 hours, 47 minutes and 3 seconds, then discovering that saved work and/or reduced consumption over the period allows the working week to reduce in the next period by 2 minutes and 14 seconds. This and other considerations explained in section 7.9 suggest the working week should change only in increments of half-hours or full hours. Doing so also seems practical for another reason. Most people do not slavishly work for every minute of every working hour, but rather have some leeway for putting in a little more or less effort to suit needs and circumstances. So, if the working week reduces by a half-hour or so, most workers can probably continue to do all they had previously done without needing to bring in extra help – which actually assists in reducing working hours further for everyone. This certainly seems practical for the future day when CAPE has reduced working hours to an amount approaching the minimum necessary to perform all work needed and wanted, when changes to the working week seem likely to reduce in both frequency and degree.

7.3 Attitudes & Motivation

“…we have been trained too long to strive and not to enjoy.” – John Maynard Keynes[390]Some people might object to the very idea of a much shorter working week in the belief that increased leisure-time spoils people, and encourages hedonism and anarchy. Yet, probably, CAPE will reduce working hours gradually, not suddenly, thus giving everyone plenty of time to adapt. Furthermore, the duties and responsibilities required by a properly functioning plurocracy should occupy some part of the time freed up by a shorter working week and so discourage harmful hedonism and anarchy, while encouraging tolerance for genuinely harmless self-indulgence.

Even if accepting a shorter working week, some might fear that an economic system free of profit is bound to miserably fail because of a supposed lack of incentive. Soviet socialism might be cited as an example of what happens without profits to spur people on. Yet the issue lacks such simplicity. Soviet socialism failed because of a lack of incentive, certainly, but this was surely encouraged more by its authoritarian political structure than by its absence of profit. In marked contrast, plurocracy provides participatory decision-making – therefore, citing the opposite political system of Soviet socialism only raises an irrelevance.

In any case, rather than leading to a lack of incentive, plurocratic self-government and vastly increased spare-time provide opportunities to unleash rather than quell our potentials, to motivate greater responsibility and creativity, and to enable us to construct a world free of the ecological and social degradation that (all but) inevitably follows from L$D-competition – the last seems a goal not only full to the brim with incentives, but also truly able “to organize and measure the best of our abilities and skills”.[391]

With or without these incentives, a vastly shorter working week won’t prevent the need to use time productively, and for reasons far more sustaining and ‘natural’ than the current ‘need’ to work – reasons such as the urge to avoid boredom and to feel useful and valued (or, if you prefer, to satisfy and please others)… the thrill of achievement… self-development and the hope for immortality through exceptionality… and the satisfaction of basic needs and desires. Fulfilment, not as consumers or producers but as members of an integrated world community, provides the ultimate incentive.

As for the selfish motivation forced by L$D-competition, that can be shed without concern. An experiment with apes demonstrated the problems of relying on the pursuit of self-interest as incentive: when their performance of ‘work’ determined their reward or punishment, the apes’ standard of work “began to degenerate until they produced the bare minimum that would satisfy the experimenter.”[392] Clearly, apes have plenty in common with humans.

Even so, market proponents might still insist that a system lacking the competitive pursuit of profit goes against ‘human nature’, which (they might claim) the current economic game merely reflects. But this has it back to front: our current ‘business culture’, especially its revered goal of profit-maximisation, does not reflect ‘human nature’, but rather crafts a temporary straitjacket from which ‘human nature’ struggles to escape. As Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett put it: “rather than assuming that we are stuck with levels of self-interested consumerism, individualism and materialism which must defeat any attempts to develop sustainable economic systems, we need to recognize that these are not fixed expressions of human nature. Instead they reflect the characteristics of the societies in which we find ourselves and vary even from one rich market democracy to another.”[393]

To a dominant extent, ‘human nature’ is determined by the specifics of ruling institutions and societal conventions, not vice versa. Change the economic game and ‘human nature’ alters too. For example, the practice of Soviet socialism moulded the ‘nature’ of its practitioners, but when Eastern Europe’s centrally planned economies converted in the 1990s to ‘free’ markets, many once docile, unquestioning followers turned into aggressive demonstrators, coup defeaters, and profit-hungry capitalists. If L$D-competitors were to experience a change of economic game, their 'nature' would likely change to a similar degree.

Anthropological studies of other cultures also demonstrate that a competitive ‘nature’ is neither natural nor mandatory. According to John Langdon-Davies, Nicobar Islanders play (or played) sports which have “no starting point and no winning post; and… whilst they compete… side by side, struggling for all they [are]… worth, if one side begins to find that it is getting a little ahead of the other it will very soon slacken off a bit and let the others get ahead.”[394] Trobriand Islanders near New Guinea also ‘compete’ oddly with their yam-growing: “The gardener spends much time on unproductive labour, decorating his garden and using better materials than are needed for the proper growth of the plants; he grows far more yams than he can use, and cheerfully leaves half the harvest, if it is abundant, to rot; and finally, he is content with a social convention which allows him only one-quarter of his harvest for his own use and makes him give away the rest chiefly to his relations-in-law.”[395]

Agree to define any set of conventions, institutions and/or economic game rules, and ‘human nature’ changes accordingly. In the words of Langdon-Davies: “Put the son of a bricklayer in infancy with the family of a Trobriander gardener, he will grow up with the traditional outlook towards yam culture of his foster parents. And from this it follows logically that a different set of institutions in the future may alter the human motives behind action and work, just as they have so frequently altered in the past.”[396]

The very “different set of institutions”, mechanisms and approaches of plurocracy and CAPE at the least foster, in Trainer’s words, “a greater readiness to connect means and ends in our thought and action… We would be spending most of our time in situations where we had to think about the outcomes and consequences of our actions because we would directly experience those consequences.”[397] Because of this, plurocratic co-operation also assists in the control of aggression and desire for power (in marked contrast to how L$D-competition ‘naturally’ encourages them). Even so, the desire for power cannot be abolished. Even in Aldous Huxley’s utopian novel, Island, in which a society operates with social and political arrangements that largely prevent domination, some people retain a potentially destructive desire for power. To reduce the likelihood of them causing trouble, they are trained in sensitivity, awareness, and the consequences of action, and also have their energies redirected. In the words of a character from the novel: “We canalize this love of power and we deflect it – turn it away from people and to things. We give them all kinds of difficult tasks to perform – strenuous and violent tasks that exercise their muscles and satisfy their craving for domination – but satisfy it at nobody’s expense and in ways that are either harmless or positively useful… [such as] fell[ing] trees… or… mining.”[398] A plurocratic CAPE-assisted future will be advantaged by adopting similar approaches.

7.4 Determining & Doing

“…the classical law of ‘supply and demand’ is structurally and semantically an animalistic law, which in an adult human civilization must be reformulated. In fact, an adult human civilization cannot be produced at all if we preserve such fundamental animalistic ‘laws’. – Alfred Korzybski[399]Even if persuaded about the issues just discussed, devoted proponents of free markets might still bristle at the idea of sharing all necessary work, with clichéd fears of socialist planning leaving them (hopefully) speechless – but again their fears are not warranted. Not just sharing work, but figuring out what work – public and private – is really needed and wanted, and ensuring it suits priorities appropriate to circumstance and culture, locally, regionally and nationally, cannot be left to central planning by faceless bureaucrats and party apparatchiks, any more than it can to profit-obsessed CEOs and marketing managers. Instead, people can determine their own needs and wants and how to satisfy them, more or less plurocratically.

Plurocracy certainly eases the task of identifying necessary work and sharing it. While specialist co-ordination and advice at times will be needed – contributed, as mentioned, by planners at higher plurocratic levels – especially regarding the latest innovations, newly invented products, and availability of resources, mostly requirements can be determined and fed into the plurocratic online communal noticeboard at the base-electorate level by the people themselves, then tallied and tabulated at successively higher levels, up to (and for some concerns even beyond) the level of a nation.

Plurocracy can thus be used as a market surrogate, enabling needs and desires for goods and services (and provision of labour) to be identified and accrued from the bottom up, and assisting producers and workers to plan and employ resources accordingly.

Given the task involved, it seems wise to play safe and overestimate rather than underestimate needs, so that an economy’s planned total production might perhaps usually exceed its anticipated consumption (although periodic CAPE revision can refine this to the minimum necessary level of ‘cautious excess’). Similarly, because not everything in life can be planned, each person’s ‘requirements’ might perhaps include an additional individually nominated percentage of their total anticipated expenditures, this percentage devoted to discretionary ‘impulsive’ purchases – items they do not expect to buy but might if the mood takes them. This would increase production and the working week across the board, but the obvious consequence provides clear motivation to keep the percentages fairly small.

Once the necessary work is identified, co-operatively sharing it is assisted by the same online mechanisms, with people nominating themselves for specific work. Personal choice, needs, skills, dispositions, and experience – as well as practicalities such as location and transport availability – should continue to play the dominant roles in determining who gets what work. However, people are always going to see some work as odious or undesirable, and it seems unreasonable to expect a cooperative society to require those jobs to be performed by an unlucky few. Rather, true cooperation requires all to take on an equal small share of work that none or too few want to do.

Once established which work lacks workers, people can choose which of the unwanted work they prefer. But probably still some work will lack sufficient volunteers, and have to be assigned – perhaps most fairly by periodic randomisation, subject to the constraints of spreading the load evenly, and not forcing people to work impractically far from home or to do labour for which they clearly have no suitability (for example, abattoir work for vegetarians). Even then, volunteers’ online recording can indicate they prefer to swap or give up any assigned work to others less repelled by it. Certainly, hard and fast draconian solutions need not be imposed, but all willing participants need to be prepared to compromise to some small extent, and to accept their plurocratic duty to make responsible choices.

Because a person’s skills often dictate their preferences, allowing people to choose their own work as much as possible actually encourages efficiency (unless their work preferences too frequently change). However, economic efficiency – output purely as a ratio of input – should not take on too much importance. In Huxley’s Island, he describes a sound approach: “We think first of human beings and their satisfactions. Changing jobs doesn’t make for the biggest output in the fewest days. But most people like it better than doing one kind of job all their lives. If it’s a choice between mechanical efficiency and human satisfaction, we choose satisfaction.”[400]

For similar reasons, people can choose not to work. Giving everyone a choice rather than an obligation to work has consistency with the guideline previously suggested – that everyone has a right to do as they see fit, as long as their choices fulfil the duty not to harm others in the process. However, each individual has to assess for themselves whether choosing not to work shirks their plurocratic duty to not make harmful choices.

Of course, some people might indulge in selfish habits (although, if persisting at them for long enough, they seem likely to be penalised in some way, or at least ostracised, by their communities – certainly, poor choices can be at least discouraged, as the end of section 7.8 explains). Yet surely the vast majority of a participatory and cooperative plurocratic community – liberated by minimal working hours and the abolition of any need to compete – will see responsibility more as gleaming with reward than reeking of effort, and will be motivated to make a responsible choice, at least partly because they can do so without coercion.

Even so, the potential difficulties of finding willing workers for all necessary work should not be understated – but nor should they be exaggerated. Much of the really necessary work done today has minimal learning curves, and in some cases need not even require training by experienced personnel but instead by audiovisual means. Some jobs won’t even need the same staff for an entire CAPE period, but can involve different people working each week or each several weeks, if that suits willing workers’ overall preferences. That might mean a little more time spent working overall than more stable staffing allows, but unless the difference proves extreme, efficiency, as mentioned, should not take priority over satisfaction.

On the other hand, having some jobs lack for full-time workers fosters multiple skills and self-sufficiency, which have the potential to lower costs and prices and working hours even further. Consider, for example, an early job of my own (between University years), at a hi-fi speaker manufacturer, where components were assembled and manually connected. The ‘skills’ took less than half an hour of training to learn, and reasonable proficiency was usually achieved within half a day, but the repetitious nature of the work probably permanently dooms it to widespread unpopularity. However, anyone so disposed might be inclined to happily do the work for a week or several, if they have the option to do as I did: work beyond their required hours to assemble a pair of speakers for their own personal use, paying only for the cost of parts, the labour not ‘charged’. (Mine still work as well as ever, albeit after needing repairs to one component, almost fifty years later.) The same approach can be adopted by anyone wanting a new bed, curtains, or most anything, though of course CAPE has to take it all into account in advance. Sharing ‘unwanted’ work in this way, however, not only gives people knowledge and skills, it also means fewer monetary costs, which, because of CAPE means lower prices and reduced working hours for all.

7.5 Affording

“It is not a question of what we can afford, but of what we choose to spend our money on.” – E.F.Schumacher[401]As section 7.1 mentioned, even with CAPE deliberately manipulating prices so that their total balances the total costs of an economy, the prices of individual products need not equal their costs of production. Indeed, the costs of work seen as genuinely productive but inherently ‘unprofitable’ (in the commercial sense of the word) might rarely balance the prices of the goods it produces: instead, to be more easily afforded, any good’s price can be set lower than its cost, even free, as long as other goods’ prices are increased proportionally (as in the example of Figure 7).

Given a choice, people might indeed prefer some goods to be made free – housing, education, health care, a reasonable minimum yearly quota of staple food and basic clothing, and perhaps more. Making most of these goods free (or even heavily discounted) should not lead to shortages or rationing: as Sherman wrote, in regard to “the basic necessities of life, public transportation, some food staples, and a certain amount of housing space… demand for these goods is not elastic and would not increase much when they become free.”[402]

But CAPE’s capacities extend beyond free or discounted goods. As long as people are prepared to do the work, CAPE allows them to afford anything they consider worth producing or in need of doing – any private or public sector cost – whether or not it directly results in finished consumable goods: community and neighbourhood projects, such as construction of meeting halls or playgrounds… new homes and infrastructure… research and development… public works, roads and all other endeavours now paid for by government, including welfare for the disabled, retired, injured, and anyone genuinely unable to work… restoration and preservation of the environment… international development and aid… entertainment, sport, art, and any discretion that cultural values and circumstances make a priority.

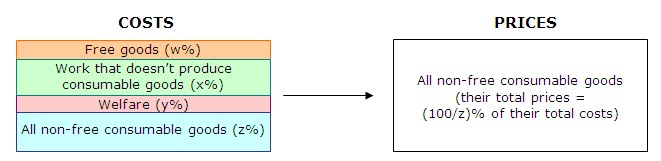

Any worthwhile work that does not produce consumable goods can be CAPE-afforded simply by increasing the prices of all non-free consumables by the appropriate proportion. In the broad example of Figure 8, all such work is priced free for simplicity of explanation (although any part of it can instead be assigned a discounted price) and is, in effect, ‘absorbed’ (like an overhead) into the prices of all non-free consumables. (Yes, Virginia, there really is such a thing as a free lunch.)

Figure 8: Affording What’s Needed

In this way, CAPE can even replace insurance: prices can ‘absorb’ an estimate of likely costs, based on recent trends, of all repairs anticipated to be needed for natural disasters and misfortune. Indeed, prices can be set to absorb even a nominal amount for unanticipated expenses.

No, this approach does not lead to outrageous prices for consumables: CAPE’s balance between total costs and total prices ensures all goods can be afforded by definition. Consider too: if you don’t pay anything for your most fundamental needs like housing (including mortgages and rent) and basic food and clothing, you have less to spend on, and a much greater disposable income – especially if you don’t pay federal taxes, local council rates, state government charges, stamp duty, payroll tax, sales tax, or any other direct or indirect tax.[403] Even if prices of non-free goods exceed those now current, so too will your capacity to afford them. But prices will probably decrease compared to now, because if the working week is substantially reduced to include only useful work, then CAPE requires the reduced costs to be balanced by similarly lower prices.

So, with CAPE, no longer does the question ‘what can we afford?’ take priority, but rather ‘what do we need?’, and ‘what do we want that we’re prepared to work for?’

The extreme flexibility of individual CAPE prices, however, prompts another question: how can they be determined without L$D to (mis-)guide us? The last section explained how both needs and work-sharing can be determined by plurocracy functioning as a market surrogate, and not surprisingly this offers a similar solution for the establishment of prices… and wages…

7.6 Plurocratic Market Signals

“If economics is so defined that it depends for its validity on the impersonal operation of the market, then it is obsolete.” – John K.Galbraith[404]The flexibility of individual prices (free, discounted, or otherwise) allows them to be set as the average plurocratic vote of their ‘worth’ and/or ‘desirability’ to the community. This is not a requirement – the findings of any suitably thorough and widespread survey can also be used, indeed any set of prices that satisfy CAPE’s requirement of balancing price and cost totals can be adopted (even current prices uniformly adjusted to balance total costs) – but plurocratic nomination of prices seems the most consistent approach.

Wage rates can also be plurocratically nominated, to ensure labour’s contribution to communal well-being is rewarded in proportion to its ‘worth’ and/or ‘desirability’ to the community (taking into account the exertion and tedium involved, associated resource costs, and the experience and capacity of those doing the work).

One approximate form of plurocratic wage-nominating took place in 1987-88 when the Australian National University surveyed 1,650 people as to what they thought certain work deserved to be paid.[405] ‘Unskilled work’ was nominated the lowest reward, only slightly less than the then actual average income, while the highest wage of just over four times the lowest was voted to a ‘work’ category called ‘corporate chairman’.[406] In contrast, in L$D-competitive economies, the highest paid receive thousands times more than the lowest paid (often for nothing more egregiously skilful than staying awake at board meetings, or possession of artistic fashionability or ordinary vocal chords camouflaged by self-exploiting exhibitionism, or the ability to mumble vowel-less sentences under constrictively tight hair bands). So, clearly, if people are given a chance to plurocratically nominate wages, they will most probably select very different figures to those now extant.

Plurocracy can also settle on the amount to be paid to recipients of welfare. However, various surveys concerning the minimum amount of money required for material satisfaction[407] have consistently found a figure of half the average income. Similarly, research of people pursuing “alternative lifestyles in Australia… [found] their average expenditures were around half the national average… None of them reported any sense of material deprivation.”[408] For these reasons, payments of welfare – perhaps better renamed “citizen’s wages” – seem most appropriately set as half the average income.

However they are determined, citizen’s wages and rates for specific work can all be more or less permanently fixed. Because whenever prices rise or fall, purchasing power is protected by CAPE’s adjustment of average working hours, L$D-competition’s usual motivation for seeking increases to income disappears. Wage rates need only change when plurocratic agreement is reached that circumstances have changed enough to make any existing wage rates misrepresentative of the work’s value to the community. The rest of the time, static wage rates will simplify the process of using CAPE.

Like wages, plurocratically nominated prices will probably also differ greatly from today’s. Once determined, though, however much they change because of CAPE, their relative values will remain indefinitely (unless revised plurocratically, like wage rates, because of changes of mind): if any product starts out with a low or high price relative to others, it stays relatively low or high, whether prices rise or fall in line with the working week – if widgets initially have twice the price of flambers, they retain that ratio however prices are adjusted to match changes to working hours.

Free market proponents might react with horror at the very thought of plurocratic nomination of wages and prices. Ignoring how the process, by taking everyone’s opinion into account, seems more likely to create accurate market signals than does L$D-competition and its many imperfections, market advocates instead might make hasty comparisons with the alleged dangers of wage-price controls. Governments sometimes implement controls by ‘freezing’ prices and wages or by setting maximum values (‘ceilings’) for them – but they do so rarely, usually only when they can’t otherwise control inflation, notably in wartime. Indeed, governments mostly resort to controls only as a last desperate “attempt to interfere with the operation of the imperfections in the market rather than to interfere with the market itself… during periods characterized by an inflationary psychology [when] market prices are not very reliable signals for resource allocation, implying that temporary guidelines or controls can be imposed without seriously disturbing the allocative mechanism.”[409] Even so, these last desperate attempts usually prove successful, as the USA demonstrated in World War 2, the Korean War, and the early 1970s. Critics claim controls merely postpone inflation, but proponents suggest they not only delay but also ultimately reduce inflation.[410] Nevertheless, the most stable prices have usually been achieved in countries attempting not just bureaucratic price control from above, but restraint from within, where workers, unions, employers, and governments all negotiate to pursue claims designed not to have impacts that feedback negatively on the original claimants.[411] Plurocratic nomination of wages and prices takes such an approach much further, but earlier success with controls and restraints suggests reasons for optimism.

Further optimism is suggested by considering the different motivations likely to be involved in setting wages and prices plurocratically: because competitive markets aim to maximise profits, they cater to financially-backed demand rather than need, but without profit, a plurocratic surrogate market can use CAPE to prioritise need, to act ethically, and to behave more like ancient markets where people sought mutually beneficial exchange rather than private gain.[412]

Plurocracy and CAPE also allow another option sure to dismay free marketeers…

7.7 Stewardship

“…a transformation of ownership is essential – without it everything remains make-believe.” – E.F.Schumacher[413]The possibility of free housing, briefly mentioned in section 7.5, may evoke thoughts of socialism and collective ownership. I have something else in mind – and not just for housing.

Like staple food and other free goods, the costs of developing land for use, and of building homes and fixed capital such as factories, can be CAPE-absorbed into the prices of all non-free goods and services – in other words, land, homes, and fixed capital can be made free. Doing so renders stocks, bonds, and other destabilising speculative money-raising devices, as well as home mortgages and business loans, (deservedly) obsolete.

It can be afforded quite easily.

The costs of fixed capital are now already effectively absorbed into prices: for success in a competitive economy, prices have to be set high enough to cover all of a business’s costs including the building of its factories or other productive capital necessary to produce its goods. Doing the same via CAPE therefore poses no additional difficulty. But although as much as twenty percent of total national expenditure is now spent on building new fixed capital,[414] these costs reduce markedly for a co-operative CAPE-assisted economy that abolishes unnecessary and unwanted work, and sheds interest, shares, and various other cost-raising artifices employed to pursue L$D-competition’s goals of more jobs and more profits. Such an economy also has less need for new capital, as it does not contrive new wants, or build to obsolesce. For all these reasons, CAPE-absorbing capital costs into prices of all consumables can be very easily afforded.

The costs of housing also can be easily absorbed: construction of “new private residential buildings” now comprises well under ten percent of total national spending,[415] and so only a similar increase to prices is required for housing to become free. By contrast, most people now spend several times more than ten percent of their income on mortgages or rent. A CAPE-assisted economy with less work overall might have a higher proportion devoted to building houses than occurs today, but other factors might compensate or even result in a lower proportion. With less work overall, some buildings now used for business – such as factories and retail outlets, but especially skyscrapers and office blocks – will become superfluous, freeing them up to be used for housing instead[416] (very comfortable housing in many cases). Many ‘summer’, ‘beach’, ‘holiday’, ‘second’, ‘third’ and so forth homes owned by a fortunate minority also offer an additional housing supply if shared properly. Indeed, a developed co-operative economy might find it has more houses than it needs, or at least less need to build more[417] or replace existing dwellings (especially when its population stabilises as the economy attains sufficient development[418]). And with seventy percent of current work gone, construction costs reduce, especially with no interest on loans, no government charges like stamp duty and sales tax, and reduced obsolescence. Even labour costs reduce, because CAPE motivates builders to complete construction as efficiently as possible, to save work. So free housing becomes very possible.

Yet without an associated price, free land, housing and fixed capital cannot be bought by a highest bidder. Therefore, neither can any of it be owned (or rented). Instead, it is plurocratically stewarded…

People living in the smallest plurocratic electorate with borders fully enclosing unused land steward it. They have responsibility for looking after the land until they agree on how, if at all, to use or develop it, with larger principles and interests protected by the plurocratic decision-making process.

Fixed capital is stewarded mostly by the people operating it – all the workers of a factory, for example – but also, and ultimately, by those most directly affected by the capital’s operations: those living in the smallest plurocratic electorate with borders fully enclosing the capital. Such an arrangement encourages ecological and social care, which CAPE ensures can be afforded.

Stewards of fixed capital make all relevant decisions about operations and practices, although issues can be raised by anyone, including members of nearby plurocracies affected by the capital’s day-to-day activities. Stewards are motivated to at least maintain if not increase the productivity of their operations, because doing so either saves work or increases production, and so contributes to the total economy’s prospects for CAPE-reduction of the working week and prices. Lower productivity, on the other hand, though calling for attention, need not be treated as a cut-throat disaster – it can be compensated for in the next CAPE period with raised productivity. If productivity consistently falls, however, stewards are obliged to investigate their capital’s viability and determine whether its continued operation is warranted.

With responsibility for performance falling largely on the workers themselves, they need to co-operate more or less as equals. Jobs naturally have specific individual duties, different wages, and undoubtedly most have some supervisory content, but all workers share a general responsibility for efficiency and care, and a plurocratic say in any major decision. (Many existing companies have already moved in similar directions, and with often astounding success.[419])

In contrast, home stewards have all the usual rights bestowed by ownership, except they cannot sell their houses – but neither do they need to afford to buy another. Responsible home stewards simply move house – the more responsible their stewardship, the greater their options. Any time residents intend to move house, an inspection is made by appropriately trained people charged with establishing – via a consistent, plurocratically agreed procedure – the building’s condition and its corresponding ‘value’: an estimate of what it would cost to rebuild the home from scratch to its current state (with some allowance made for its location, proximity to services, and other advantages and disadvantages, such as, for farms, the state of soil and land). If people leave a house in worse condition than when they move in – if its value, adjusted to take CAPE-fluctuations into account, falls during their tenancy – they can only move to places of equal or worse condition (those with equal or lower value). But if tenants/stewards improve a home before leaving, this grants them the right to move to higher-valued residences. Houses with unchanged conditions also probably allow some ‘upward mobility’, but to a lesser extent and not too often. Each plurocracy determines for itself the exact rules to use, and has responsibility for planning the building of houses and ensuring the costs are covered via CAPE – but occupants still have responsibility for maintaining their homes. This motivates proper care of the homes even if they are not ‘owned’.

This more consistent – more ‘real’ – form of real estate is accompanied by the use of waiting lists. If people favour a house (or even a particular street, locality, suburb, town), they put themselves on its waiting list, and when it becomes available, those nearest the top of the list who find it convenient, and who have eligibility (as per their house’s value), move in. Most might choose to increase their chances by putting themselves on several homes’ waiting lists; others might choose to avoid waiting lists entirely due to the availability of houses vacated without anyone waiting on them. If waiting lists, house ‘values’, vacancies, and transfers, are all recorded on the plurocratic online communal noticeboard,[420] the ease with which people can then indicate their intentions, choices, and actions, enables all to be treated much more fairly than at present when a home’s ‘value’ is determined almost solely by what the manic-compulsive market (double)thinks.

Perhaps, too, home waiting lists can be used to reward or punish exceptional behaviour. Bravery, genius, extreme efficiency, creativity – if the community plurocratically agrees – might lead to a jump, or several, higher up waiting lists, whereas extreme laziness or persistent irresponsibility might force a fall down lists (something like this last option is indeed advocated in the next section for providing additional motivation for those not willing to pull their weight).

The homeless, needless to say, deserve first choice of all vacant homes. No excuse can be made for advanced and supposedly civilised societies which condemn even one of their members to living under railway bridges or inside tunnels, kept alive by handouts from charities, isolated, unwanted, half-frozen at night, and semi-catatonic during the day. In an environment of plenty, none should lack a home. It can no longer be accepted – if it ever could – that the homeless have only themselves to blame, that their own laziness or alcoholism or violent tendencies have exiled them; in each recession, the ranks of the homeless swell with people retrenched from long-held jobs and unable to gain work no matter how hard they try. Rather than confusing cause and effect, and trying to pin the blame on the homeless themselves, we should simply make economic arrangements, such as free housing, to avoid such sorry circumstances.

None of the above implies or suggests the abolition of private property, it merely recognises the distinctive communal nature of land, homes and fixed capital. Land cannot be owned, whatever the artifices of law suggest, instead it is merely acquired, by whatever techniques work at the time – now mostly legal, but once, in many nations, often based on the brute force of ‘colonisation’. Fixed capital and homes, as demonstrated, can be stewarded in a similar fashion as land. But for everything else that can be purchased, the buyer owns what she/he buys, and private ownership seems more suitable than any alternative.

As for the actual process of purchase, of monetary exchange, the next section details an approach which allows all of the above ideas to be implemented in a simple, straightforward and consistent way, while reinforcing all of the ideals and aspirations to which these ideas are directed…

7.8 Accounting

“Are we to be an authoritarian society which believes that people are too irresponsible and frail and selfish to make responsible decisions for themselves; that people must be manipulated and cajoled and told what they should or should not do? Or are we to be libertarians who believe that if people are given the responsibility of being participants in their own destiny, rather than patients, they will astonish us by being as responsible and sensible as we are?… By denying people responsibility, an authoritarian society makes them irresponsible.” – Robert Pritchard[421]With CAPE, not only is the pursuit of profit abandoned, and businesses stewarded rather than owned, but individual producers do not even have the capacity to set or alter prices of their goods. Some even have to accept that their goods are sold for free. But all of this can be handled easily enough if…

Every producer of goods or provider of services has an account, in a centralised database, which is credited at the start of each CAPE period - henceforth treated as a year - with an amount that fully covers their expenditures for the work plurocratically planned to be done by them over that year. When a good or service is purchased, an EFTPOS- or e-wallet-like point-of-sale payment system debits the account of the purchaser by the price, but credits the account of the producer of the good or provider of the service with the cost of producing or providing what was bought.

Over the year, some producers and providers undoubtedly spend more or less than they expect, or sell fewer goods or services, or suffer shortfalls – so by year’s end, their accounts differ from at the start, thus providing data to inform future allocation of work and resources and related plurocratic CAPE-planning. Nevertheless, at year’s end, producer accounts are reset: after their end-of-year balance is archived in the centralised database, it is replaced by a credit amount equal to the next year’s planned CAPE-expenditures.

The same approach handles the building of capital goods, except the ‘producer’ account might more accurately be termed a ‘project’ account, and no purchases of produced goods balance expenditures. For example, say a plurocratic region deems it needs a new hospital: costs of construction are included as part of the region’s total costs, with prices and the working week calculated accordingly via CAPE for the region and higher level plurocratic electorates ‘containing’ the region. So, at the beginning of each year, the project has an account recorded with its expected costs for the period. As work done on the project is paid, its account dwindles, but at the end of every year until the project is completed, the account is reset with a credit sufficient to cover its anticipated expenses for the following year. Any differences between the final figure at the end of each year before re-setting the account is used to assist better subsequent planning, but these ‘discrepancies’ have no more significance than that.

Consumption is accounted similarly, but with an important difference. Each worker is credited their full year’s income at the start of each year, and citizen’s wage recipients likewise (or, more likely, this is done weekly, fortnightly, or monthly, so people retain frequencies of payment to which they are accustomed). As people spend, their accounts dwindle. But unlike producers, consumer accounts are not reset at the end of each year, rather they accumulate, and so function as statements of each individual’s overall contribution to their community. Hard workers and frugal spenders keep their accounts mostly in credit. Big spenders and lazy burdens, on the other hand, have accounts more often in debit.

These arrangements make all forms of money-lending redundant, as well as mortgages, compound interest, and superannuation. They also radically reduce the roles of banks and financial institutions: not only can they not collapse because savings cannot disappear into thin air, but the few ‘banking’ functions still required can be performed mostly via periodic centralised crediting of all accounts and decentralised point-of-sale debiting. Even money can be avoided in its usual form. If plurocratic choice decides that cash remains an option, then as a consequence of income corresponding to time worked, a suitably authorised statement or ‘notification’ of work performed can easily function as cash (or more closely perhaps, given that each statement could only be used once, to cheques or ‘buying orders’). But whatever form cash takes, it requires a far more manual adjustment of CAPE accounts compared to the automated method previously described and resembling EFTPOS and e-wallets - which perhaps argues persuasively against using "cash". Other than these minor practicalities, however, there seems little role for banks or banking – and none for central banks, discount rates, open market operations, and all the rest of current monetary regulation.

“Unrestricted credit!” I hear free market zealots cry in utter exasperation. So what would stop a person from simply refusing to work at all, yet still spending like a millionaire? Even if those who deliberately and consistently choose not to contribute are denied citizen’s wages when otherwise eligible, they could still run up unlimited debts.

I suggest that few people would abuse a system built around cooperation and sharing of both the work and the fruits of that work, especially with community approval likely to play an even more significant role than it does now. Those who did fail to pull their weight would likely have personality problems of a scale that would make them difficult for any system to handle. Nevertheless, probably few could persist for long without ending up shunned by their communities – which might well change their minds as “the tendency to ostracize people who do not co-operate, and to exclude them from the shared proceeds of co-operation, is a very powerful way of maintaining high standards of co-operation.”[422] Most people, however, as suggested in section 7.4, would instead feel liberated – not just by stable economic conditions, and the abolition of any need to compete, but perhaps most by the absence of compulsion. They’d be motivated to make a responsible choice because they could do so without coercion. And we’re talking, remember, of eventually only one day’s work per week. So, probably, most people would keep their accounts in approximate balance from one year to the next.

Nevertheless, while no one would be forced to work, they can still be encouraged in different ways to do the responsible thing. The most obvious encouragement stems from the knowledge that if enough people take the lazy option, too few are left to do the necessary work, and then everyone suffers. Co-operation can be further, and more inventively, encouraged if anyone refusing work for more than a year or two (or with an account in debit beyond a plurocratically agreed value) is disallowed moving house except to a place of lesser value than their existing residence (the longer they refuse to work, or the larger their debit, the less the quality of housing they can choose). Similar encouragement follows if everyone’s account balance is made public information at all times (even after death), freely available online and accessible to anyone desiring to see it (likewise for producer and project accounts). Having everyone’s final account balance displayed on their gravestone or memorial plaque also seems likely to motivate most people to avoid an unflattering epitaph. As a last resort perhaps, anyone refusing to work for a long enough period might have their plurocratic voting privileges revoked until they started putting in a reasonable effort.[423] With all these and perhaps other (plurocratically determined) encouragements, a cooperative CAPE-assisted economy seems likely to involve less shirking of duty than occurs now in our L$D-competitive free-for-all.

7.9 The Fine Print

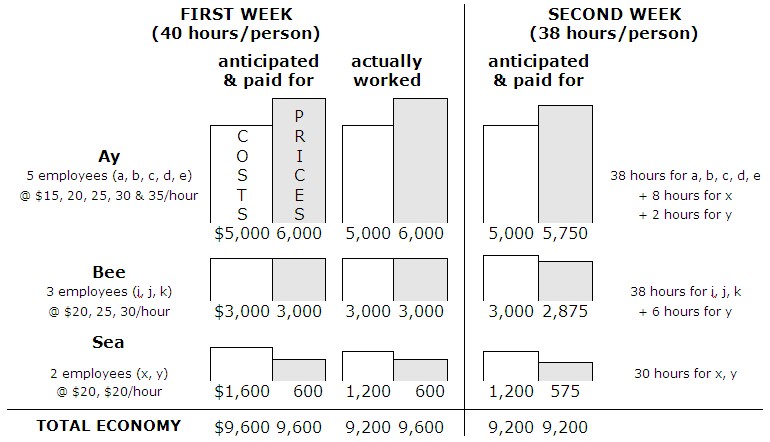

“…our current economic system may well be the most pervasive and persuasive of all our cultural hypnotists.” – Peter Russell[424]To simplify the explanation of how CAPE can reduce average working hours and prices by the same proportion, wage rates in the example of Figure 7 were carefully chosen: the employees who saved the work which allowed hours and prices to reduce are both paid the average wage rate of the other two businesses in the economy depicted in the figure. Less convenient results follow if their wage rates differ from the average.

For example, if both are paid $20 per hour, but with all else the same, then their saving of twenty hours of work gives rise to the situation depicted in Figure 9: still 380 man-hours are needed to produce the same output, but a five percent reduction in average hours to 38 hours a week requires the same reduction to total prices, lowering them to $9,120. However, the work provided by Ay and Bee to Sea’s ‘surplus’ workers, if an ‘average’ of all their employees’ work, and paid at their average wage rates – $25 per hour ie. more than they receive from Sea – causes total costs to sum to $9,200. Prices must equal the same figure, but therefore they reduce less than hours, meaning everyone other than the surplus workers (who effectively receive a pay rise) lose purchasing power, because their total income decreases more than prices.

Figure 9: ‘Problematic’ Cost And Price Equalisation

On the other hand, if the surplus workers are paid by Sea not less but more than the average wage, the opposite situation results: the hours they work elsewhere lower their income more than prices reduce, whereas everyone else effectively increases their purchasing power.

Alternately, if the surplus workers of Figure 9 are paid their old rates at all of their jobs – in effect, being underpaid for the additional work they do beyond their original work – prices and income reduce across the board by the same percentage. But, needless to say, such an outcome for the surplus workers hardly seems a reasonable or fair reward for them previously saving work. Alternately, the discrepancies can be avoided if every job is paid the same wage rate, but that also hardly seems reasonable or fair.

Similar complications arise if working hours have to increase because of lost productivity in some sectors: unless some workers are paid less or more compared to others for the extra work they must do in ‘secondary’ jobs, CAPE requires others to gain or lose purchasing power.

Is this CAPE’s Achilles heel, the flaw which renders it impractical or unusable? Perhaps so, if the average economy consisted of only a few firms and a handful of employees, but the difficulties just explained would barely register let alone pose insuperable problems for a typical modern economy with millions of people, a multitude of jobs, wages, working hours, product cost-price differences, and varying rates and even directions of productivity changes for different economic sectors and individual businesses. The size of a real economy, and the likely variety of hours required for specific jobs, allows for many more options for work reallocation than the simple examples above, and so, normally, few people will be required to do several jobs at vastly different pay-rates in the same period.

Remember too that only the net change determines CAPE adjustments necessary to the average working week and to prices. Hence, a productivity improvement in one sector of an economy can be offset by a productivity loss in another paying the same wages, and workers reallocated to suit, while keeping the average working week unchanged. Likewise for dealing with reduced consumption of one product, and increased consumption of another.

Also remember that CAPE adjusts average working hours, and not to the precise minute or second. Hence, in an economy with a variety of working hours, rather than all altering by the same proportion, certain jobs can retain the same weekly hours from one period to the next, if this is judged more suitable, but then those in the jobs either work fewer weeks in the year or retire earlier. Each and every business has to determine the most suitable approach for themselves, but always based on the need to pursue both efficiency and equity.

In any case, for CAPE to function properly, it needs to take into account many factors besides the practical specifics of work reallocation and the individual efficiencies of sectors and businesses. For example, CAPE adjustments must try to factor in the effects (actual and anticipated) of flood, drought and natural disaster on food production… age demographics (an aging population eventually leaves fewer to do whatever work is deemed necessary)… stockpiles and unsold inventories… costs of work not directly leading to goods and services, such as research and development, and their proportion of total spending… ‘hidden’ unemployment…

For instance, if the oil industry loses productivity when the economy overall increases efficiency, all prices fall including that of oil. Then, the rising unit costs for oil should be compensated for by research into alternatives. But if so, although the community works less in total, a greater proportion of its labour than was previously the case is devoted to producing as much oil as needed and to developing eventual substitutes for it – all of which has to be absorbed by the prices of everything produced. CAPE can handle this easily enough, but only if effort is made to include the consideration into CAPE adjustments.

One thing CAPE does not have to consider: private second-hand sales (although it has to deal in the usual fashion with retail shops and other producers concerned with selling second-hand goods). Although the cooperative and participatory future envisaged perhaps will more often motivate people to give away items they no longer need, if someone does privately sell a second-hand good, the seller’s consumer account increases by the same amount deducted from the purchaser’s consumer account, and the exchange is reflected entirely in those consumer accounts, without any effect on CAPE for the period in question. A significant amount of second-hand sales, however, might prompt less purchasing of new goods than planned, but then CAPE-planning for the next period will require appropriate adjustment.

Whatever CAPE does or does not take into account, generally more of people’s working time will be devoted than at present to retraining due to work reallocation. Retraining, however, comprises a cost for a plurocratic economy and so – to protect the purchasing power of those being retrained – it makes sense that everyone receives the same income during retraining as in their last job, with CAPE factoring this into account. Similarly, in the unlikely situation of the vast variety of options of a realistically-sized economy somehow failing to prevent some workers from taking on lesser-paid duties, they still need not lose purchasing power if they are subsidised any loss of real income resulting from reallocation, another small adjustment for CAPE to take into account in advance (recorded against the business employing the reallocated workers or else against a general account applying to the entire economy covered by CAPE).

Nevertheless, the explanation of CAPE so far has been restricted largely to considering only optimistic outcomes – increased productivity and/or reduced consumption leading to reduced work and prices. In the example of Figure 7, work was saved, but what if work requirements are underestimated, say because of natural disaster or an unexpected fall in productivity in a major economic sector or some other unanticipated circumstance? If, as previously suggested, people are paid for the work anticipated to be needed, even if it turns out they don’t have to do all of it, does this also work in reverse: if more work is needed than anticipated, if some have to work overtime, do they receive no payment for the extra work, in order to ensure that costs balance prices? Or, if they are paid for the extra work, how does CAPE deal with their extra income causing total costs to exceed total prices?

A similar complication concerns savings. If total costs and prices balance, whenever someone saves a part of their income over a period, it means some of the goods produced are not bought. Yet if the prices of all goods rise in the next period, including those produced but not sold in previous periods, then savers have less money saved than needed to buy the same goods they did not buy in the previous period, leaving non-savers with the advantage; whereas if prices fall, savers have the advantage. On the other hand, if price adjustments apply only to goods made in the period in question, then unsold goods produced in earlier periods can have higher prices, and so might remain unsold indefinitely.

Again, these issues complicate CAPE but do not invalidate it. Several ‘solutions’ might be applied. For instance, for each period, savings accrued can be adjusted by the same proportion as prices, and all goods, even those unsold from years ago, can have the same proportionate price adjustment – then costs and prices balance, the monetary value of all unsold stock equals the total amount saved, neither savers nor spenders have any advantage or disadvantage, and no old expensive goods exist. Similarly, overtime can be paid, but these extra costs can be carried forward into the next period with prices and working hours adjusted accordingly to compensate for the imbalance between costs and prices caused in the previous period by the overtime. Or, overtime can be unpaid, but with those doing it getting a proportionate discount on their working hours in the next period, or a proportionately shorter working life.

Which if any of these approaches are adopted will depend on how much of our existing mindsets persist beyond L$D-competition. I would hate to see CAPE and its associated ‘free lunch’ economics turn into an accountant’s wet dream. The simplest and least resource-intensive solution instead involves us simply not caring about the detail. Certainly, if consumer accounts work as explained in the previous section, responsible plurocratic citizens might aim to not spend more than they earn, but because their accounts can go ‘into the red’ without penalty as and when needed, it should make little difference to anyone if they had saved at a time of lower prices, or had received a slight excess from overtime. As long as people understand that the accounts give a fairly accurate indication of an individual’s level of economic responsibility, they can make some allowance to the figures – a little bit over or under balance, given all the potential complications, can be treated as close enough. Better that than diverting energy and resources into trying to dot every ‘i’ and cross every ‘t’ (something that can never actually be achieved anyway). Remember, CAPE aims to minimise not create work.

If things don’t balance at the end of a CAPE period, ultimately it matters only as much as it’s deemed to matter – it can be recorded to assist planning, and then given no further importance (except perhaps to evoke pride or shame if planning consistently proves accurate or not). CAPE serves an accounting role, and is meant to serve us, not the other way round as too often occurs now. It facilitates doing and affording what is needed, coping with more or less work without penalty, and reducing consumption and work to sustainable levels. All of this can be achieved at the cost of relatively small imbalances in consumer accounts if we so choose – we can rely on qualitative success, rather than pursue exact quantitative balance via layers of otherwise unnecessary complexity and second-, third- and higher-order adjustments.

Ultimately, plurocracy will determine which of the options to adopt, but for me the choice seems obvious: the fewer and simpler, the better.

Chapter 6 Chapter 6 |

Chapter 8 |